Should a RIBA House of the Year have wood stoves?

What ever happened to the concern for sustainability and health?

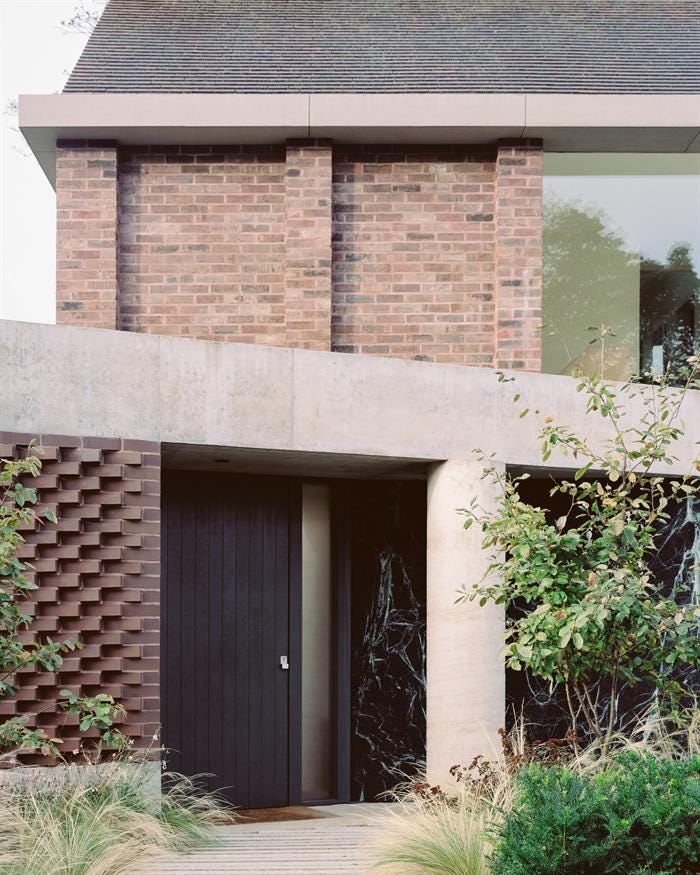

Almost every time the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) announces its House of the Year award, I wonder what they were thinking. This year, there is much to love in the winner, Six Columns by 31/44 Architects, including the use of exposed wood joists and plywood walls instead of drywall, the scale and the urban site.

What I do not love is the use of wood stoves. I have been writing for years about the dangers of PM2.5 from burning wood, asking Is Burning Wood for Heat Green? In a Word, No, and other sources, most recently in Particulate Pollution Is Worse Than We Knew, and Is Damaging ‘Every Organ in the Body’ They do not belong in urban homes.

Coincidentally, the Institute for Fiscal Studies just released a report, Exposure to Air Pollution in England, which found that PM2.5 emissions have dropped significantly in the last 20 years. The only source of PM2.5 that has grown is from domestic consumption or burning wood in fireplaces or wood stoves. The report describes the problems caused by PM2.5:

Based on epidemiological evidence, the World Health Organisation considers PM2.5 as the most damaging air pollutant. PM2.5 is made of tiny particles which can easily penetrate deep into the respiratory tract, pass into the bloodstream and enter the brain. These physiological pathways explain why PM2.5 exposure is linked to an increase in respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, and to cognitive damage.

Both short-term exposure – over the course of a few hours to a few weeks – and long-term exposure – over the course of a few years to a lifetime – matter for health. Short-term exposure has been causally linked with increased emergency hospitalisations for cardiovascular and respiratory issues and with increased mortality. Long-term exposure has been associated with increased mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease and lung cancer. One study suggests that, in 2019, PM2.5 exposure was associated with over 300,000 premature deaths in Europe.

Health Canada advises that there is no safe minimum level, and “any reduction in PM2.5 would be expected to result in health benefits, especially for sensitive individuals, such as those with underlying health conditions, the elderly or children.”

UPDATE: Since I wrote this Tuesday morning, even newer research has been published, Comparative receptor modelling for the sources of Fine Particulate Matter (PM2.5) at urban sites in the UK. The report notes that emissions from burning wood have risen significantly.

“The experts found woodburning-related PM2.5 concentrations seven times higher than those observed in 2008-2010. They also discovered that the impact of woodburning is particularly pronounced during winter months, contributing up to around half of PM2.5concentrations - a seasonal spike attributed to people heating their homes.”

Professor Zongbo Shi of the University of Birmingham says in a Dec. 10 press release:

“We need to see immediate and coordinated actions at local and national levels to reduce wood burning, improve air quality - including enhancement and enforcement of smoke control areas to curb emissions from woodburning stoves and open fires. This has great potential to reduce PM2.5-related health risks and decrease mortality in the region.”

Larissa Lockwood, Director of Clean Air at Global Action Plan, says in the release: “Lighting fires in our homes is now the largest source of toxic fine particle air pollution in the UK, presenting a range of serious health risks including heart and lung disease, diabetes, and dementia.”

Every time the owners of this house fire up their wood stoves, PM2.5 are emitted and shared with the neighbours. A few years ago, nobody would have cared; we were swimming in particulates from burning coal and smoking. There have been dramatic reductions already, and heatpumpification and the electrification of everything will make the levels drop even further. Unnecessary household burning of wood will become an even bigger portion of the total PM2.5 emission. And we don’t need to do this anymore; Architects know how to design resilient homes where we don’t have to burn stuff to keep warm.

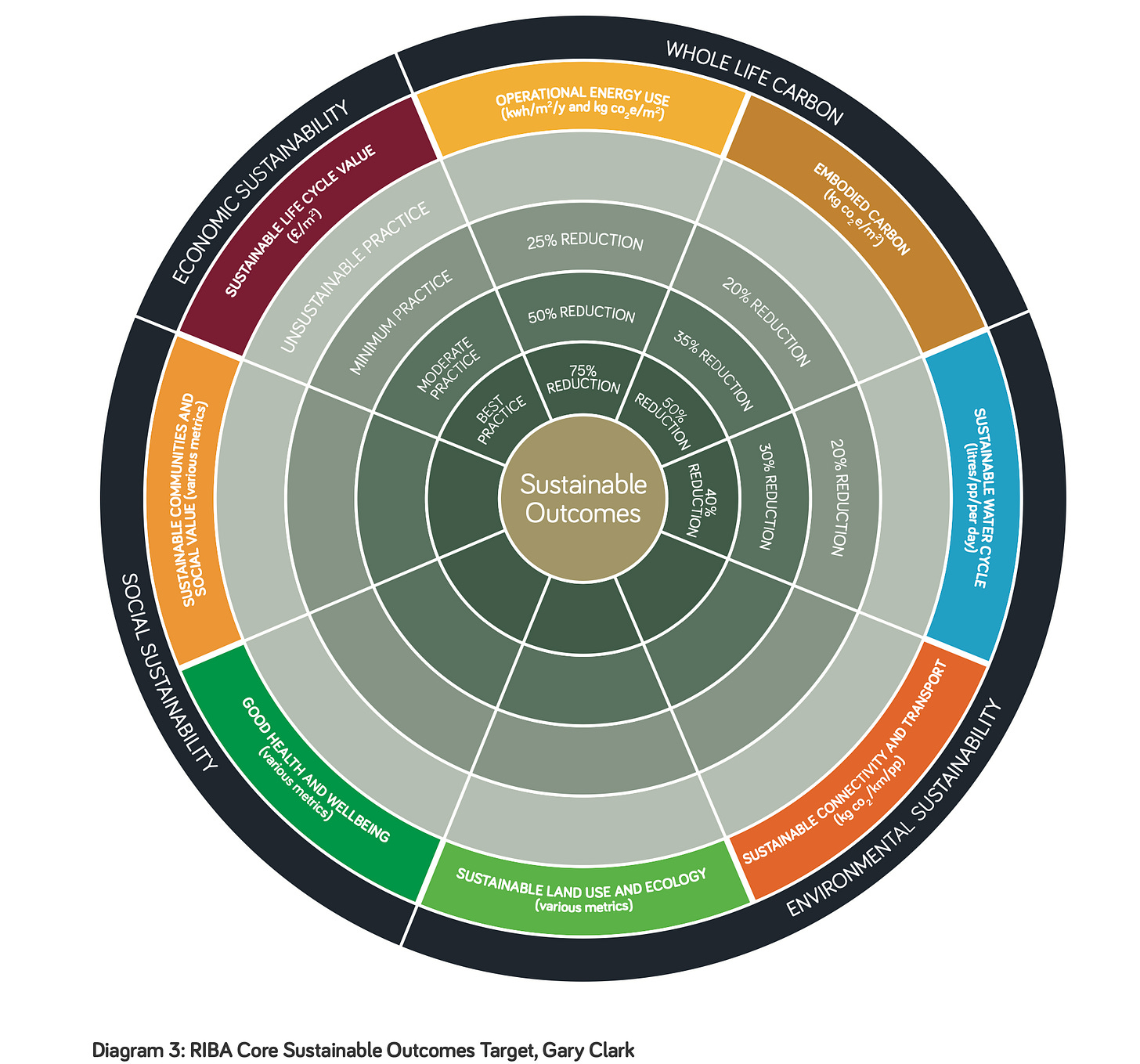

The RIBA also has standards and a sustainable outcomes guide that calls for net zero operational carbon, good health and well-being, and Sustainable communities and social value, which I assume includes not poisoning your neighbours. Perhaps it is time for the RIBA to apply the same standard to its residential award programs and have a sustainable outcomes checklist as part of the judging process.

The jury for the RIBA award was “impressed by the design’s efficiency, as much as its inventive, sophisticated use of space and materials. A single air-source heat pump also provides all the house requires for heating and washing, with bills a fraction of typical running costs.” It doesn’t appear that the wood stoves are needed.

Then there is the issue of the six columns and the embodied carbon of all that concrete, none of which is needed above grade in a two-storey house. The big RIBA awards will soon take embodied carbon into account; perhaps they should have it here.

Six Columns is a lovely home. It’s not a monster house out in the country as the house of the year often is. It looks warm and comfortable on its small urban lot.

But we shouldn’t be burning stuff anymore. We shouldn’t be building houses out of materials with high embodied carbon when alternatives are available. And we certainly shouldn’t be giving them the RIBA House of the Year Award.

I have to comment here because I heat with wood, but not a wood stove. Instead it is a masonry stove, surrounded by a couple of tons of rock. We are rural and the wood is all collected from the woods on our farm, entirely from dead trees. We do not cut down living trees for firewood. I burn only once most winter days, usually in the evening, and the fire is not oxygen limited. After starting particulate emissions are minimal, far less than a gas stove. As a professor of environmental science I am quite aware of the dangers of particulates and cast iron wood stoves are much worse than my masonry firebox. 12 hours after the burn the stone around the masonry guts of the fireplace is usually between 45 and 58 degrees C (112 and 136 degrees F), and the house is well insulated. I am not in Canada, so the need to have two burns is limited to rare cloudy days and temperatures well below freezing. Basically I agree with you. Stoves are sources of particulates and burning wood in urban areas is dangerous. However, in rural areas, with a well-designed masonry stove, the worst aspects are avoided.

You are right to point this out. As you know our house on a hill is still heated with wood, I can't excuse that any more than our dependence on a car to get around, or the inefficient form of the house we built. I try and stop others making the same mistakes which were informed by other examples.

I think you pulled your punches re other aspects of the house such as the extravagance of materials and upfront carbon (no £ budget mentioned!). I'm in no position to judge people's consumption but what annoys me is when it is sold as sustainable with 'narratives' about visible structure allowing reuse. I'd defend anyone's right to build any house they like if they have the resources but I struggle with putting it on a pedestal as a house of the year. This is a good example of architectural style dressed up as design (problem solving). It will inspire others to do the same rather than move on.

Like the rural mass stoves fed with twigs that fell from trees, or the 'harmless' racist interesting character down the pub, the individual examples can always be justified and are what makes the world a richer place. My problem is promoting wood stoves, or buildings like this, as blueprints for sustainable design. Like it or loathe it, but as I think you suggest, don't put it on a pedestal.