Preservation is climate action

We are no longer just trying to save the past; we’re trying to save the future. We are part of a larger movement

I didn’t do a post last Friday because I was in Ottawa, presenting to the 50th conference of the National Trust for Canada. They are working on a “heritage reset,” reassessing what they do, and what they stand for. I have been consulting to the Trust on the issues of climate change and did a brief seven-minute presentation at the opening plenary. Regular readers may recognize much of this from recent posts, but having only seven minutes concentrates the mind and made me distill the information, so it is a bit different and comes with a video! I had a few technical issues doing the presentation, so I have re-recorded the PowerPoint, which you can see here:

And for people like me who hate videos, I will put most of it into a post. The heritage reset is at the stage where we are asking questions-

On Thursday, I was in a Canadian Association of Heritage Professionals (CAHP) session where Vancouver consultant Elana Zysblat said, “Heritage is a thoughtful management of change.” I thought this was brilliant because we are going through a period of massive change. How do we manage this new language of carbon conservation, upfront carbon, and carbon budgets?

It requires a reset of our thinking. For fifty years, we have been worrying about energy consumption, and in the heritage community, we struggled to save leaky old buildings.

Then these guys came along, and we started seriously worrying about cutting carbon emissions.

Almost everyone knows these graphs showing how we have to cut emissions in half by 2030 and to almost zero by 2050. I have always felt that they are fundamentally a flawed approach to explaining the goal because they let people think this is a 2030 or 2050 problem when it is a now problem.

I believe it is much more straightforward to simply show the estimated remaining carbon budgets to limit global warming. Forget the ramps and the graphs; there is no 2030 or 2050 here; it is all about what we do now.

It’s all about how every ton or tonne of CO2 that is emitted now adds to global warming, which is why we have to do everything we can to limit emissions now. Immediately. Today.

When we talked about energy, we mostly meant operating energy, which keeps our buildings warm or cool. When we talk carbon emissions, there are the operational emissions that come from running a building, but there are also what some call embodied carbon emissions, which I think confuses everyone because embodied means “include or contain something as a constituent part,” and this carbon is not included or embodied, it is in the atmosphere.

It also mostly happens upfront, before the contractor hands over the keys, which is why we call that column of extraction, manufacture and construction “upfront carbon emissions.” And it’s big and getting bigger in comparison to the operational emissions as buildings get more efficient or electrified and can approach 100% of carbon emissions. These are NOW emissions that go smack up against the carbon budget.

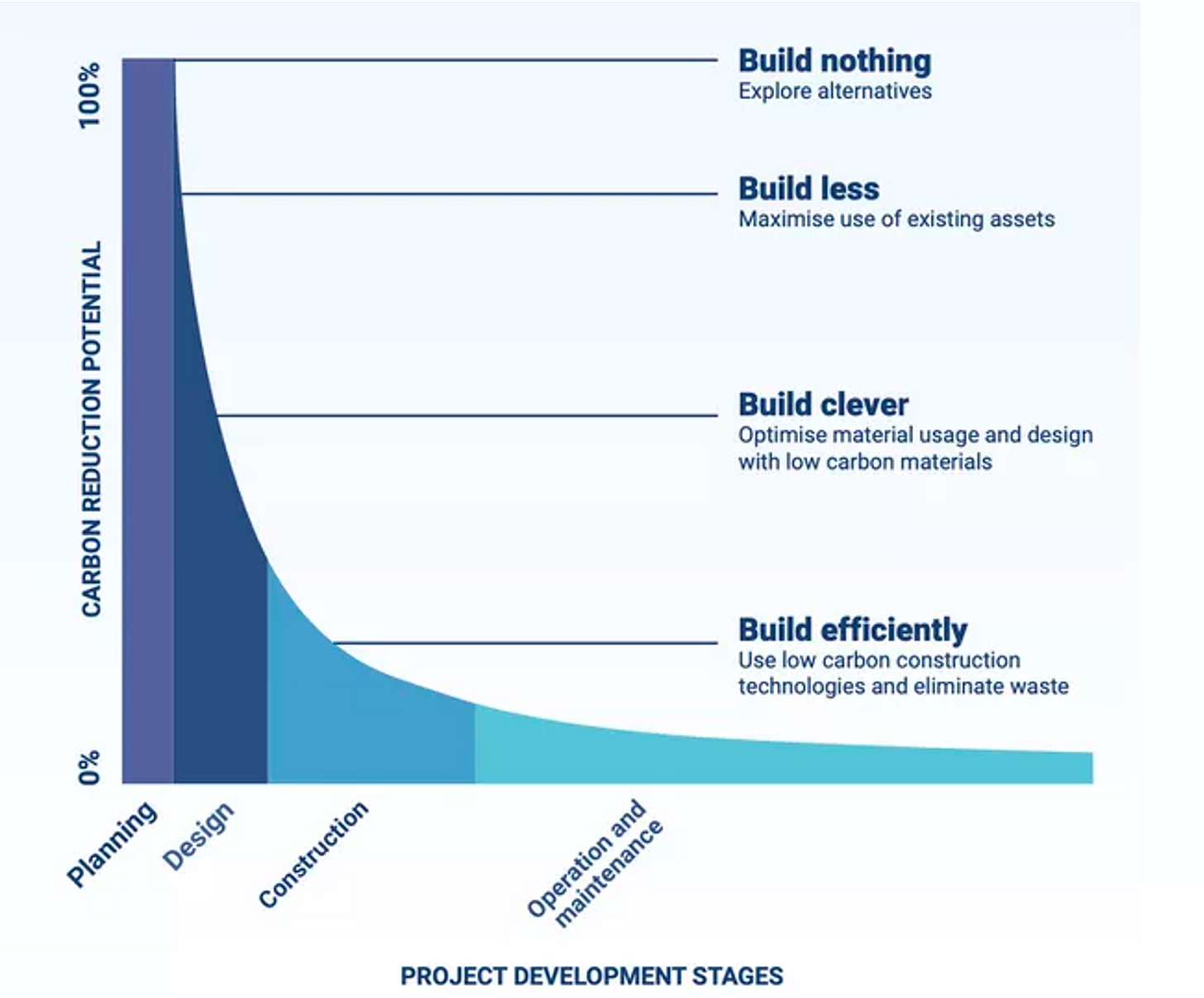

That’s why many in the industry are realizing that the best way to avoid those upfront emissions is to not build anything, and explore alternatives. Next, you want to build less and maximize the use of existing assets. Only then do you look at clever buildings made from low-carbon materials. This changes everything; I wrote earlier:

There is a fundamental change happening in the way we look at existing buildings. A dozen years ago, everyone worried about energy, and we had to justify saving buildings in the face of those who would say they are energy hogs that need replacement. Today, we worry about carbon, and those who want to tear down existing buildings must justify what’s called the upfront carbon, or the emissions from making building materials and building new structures, that happen before the building is even occupied.

It’s not just heritage types; it’s engineers like Will Arnold telling us to “use less stuff.”

It’s consultants like Preoptima saying, “When looking at existing buildings, the three magic words are retain, retain, retain. Think critically as to whether building more or building new is the answer. Do we need to use new materials at all? Remember that building nothing eliminates the potential for embodied carbon emissions.”

It’s architects like David Chipperfield saying, ‘We have to move [on tackling embodied carbon] and I would say you are smelling that already now in planning discussions. The move has to be not ‘what’s the reason for keeping [the building]’ but ‘give us a convincing reason why you can’t keep it’.”

And, it’s heritage professionals like Jim Lindberg saying, “The urgency of reducing embodied carbon emissions inverts common perceptions about older buildings and climate change. Rather than outdated structures that we hope to replace, older buildings should be valued as climate assets that we cannot afford to waste.”

Professional groups are on the case too, with Architects for Climate Action telling us to “assume demolition is not an option.” Architects Declare says, “upgrade existing buildings for extended use as a more carbon-efficient alternative to demolition.”

Heritage professionals have used legal tools like designation and listing to save buildings, but many others consider these to be obstructionist and NIMBY. But now that we are in a battle to stop carbon emissions, we can accentuate the positive.

In the UK, the demolition of the Oxford Street M&S store was considered a “carbon catastrophe” and stopped by the Minister. The director of SAVE Britain’s Heritage said “the dial has moved. The age of automatic demolition as come to an end.” Laws can be powerful tools for eliminating carbon emissions.

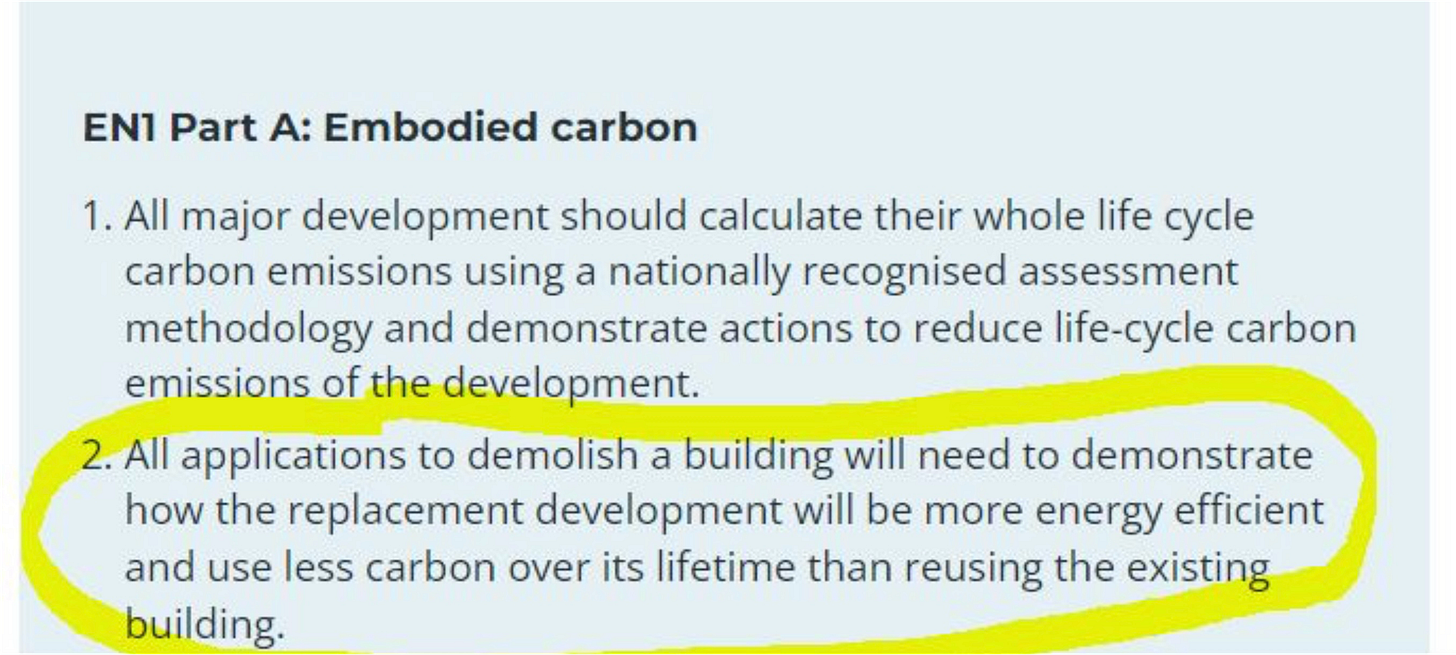

As I was on the train to Ottawa, this came into my inbox, proposed legislation in Leeds, UK, where applicants to demolish a building would need to demonstrate that any new project had lower whole-life carbon emissions than reusing the existing building. That kind of legislation changes everything.

And this is why you don’t tear down perfectly good Science Centres in Toronto or Prime Minister’s residences in Ottawa when we can renovate and restore them. At 6AM the morning of my lecture, I was trying to summarize and conclude, and came up with a statement that seems to have resonated:

The Big Reset:

We are no longer just trying to save the past; we’re trying to save the future. We are part of a larger movement because preservation is climate action.

Previously on this subject: ( I’m recycling here)

Why heritage preservation is climate action

When you look at the world through the lens of upfront carbon, it changes everything

I never get tired of that triangle graphic with the hierarchy of net zero design.

Again, I think we need to differentiate between structural ("We want to keep the building standing and in use") and aesthetic ("We want the building to look as is, forever") preservation. The former avoids upfront carbon emissions, whereas the latter, if anything, increases upfront carbon emissions because it enforces interior insulation which makes the building more vulnerable to external conditions and increases the odds that it will need reconstruction in the future.

If I want to put 6 inches of wood fiber insulation and a layer of stucco on the outside of my 1700s home, why shouldn't I be able to? After all, that's how historical people repaired and protected failing walls. If I want to install exterior storm windows, or heaven forbid, replace the old hung windows with period- (but not necessarily region-) correct tilt/turns, why shouldn't I be able to? Doubly so if wood --> vinyl replacements were allowed, as is the case in my condo building, but hung --> tilt/turn is not.