On Leisure, "positive idleness" and "negative idleness"

A bonus from my earlier book, with thoughts on leisure from Veblen, Keynes, Russell, and Hickel.

I recently saw this in Substack Notes and added my own comment, with a screenshot of a quote from Bertrand Russell from my book Living the 1.5 Degree Lifestyle. Katie JgIn also just wrote a post In a Sped-Up World, It’s Becoming a Luxury To Slow Down discussing leisure.

Leisure was one of the six “hot spots” of carbon emissions discussed in the book, and I looked at how and why we spend our leisure time as we do, and what we have to do to reduce the carbon emitted doing it. Here’s an excerpt from the book.

In 1899, Veblen could title his book “The Theory of the Leisure Class” because there was, in fact, a class of people who had time on their hands, as distinct from those who had to work. There was not only conspicuous consumption but also conspicuous leisure, which he defines as the non-productive consumption of time. Members of the working classes didn’t have much time for leisure, but the rich wanted to demonstrate how much leisure they actually had, thanks to all the people working for them. “Conspicuous abstention from labour therefore becomes the conventional mark of superior pecuniary achievement and the conventional index of reputability.” The leisure class couldn’t just have it, they also had to flaunt it: “The wealth or power must be put in evidence, for esteem is awarded only on evidence.” This may well explain the consumption of Sea-Doos and power boats and ATVs, all those expensive and powerful toys that people use to fill their leisure time.

Since Veblen was writing back in 1899, there have been radical changes. With the reduction in hours of work and increases in pay after the First World War, many more people had time on their hands. Economists thought it would continue this way; in 1928, John Maynard Keynes predicted that because of a predicted eightfold increase in productivity, we would be working on average three hours a day by 2030. He thought it would make us better people:

We shall once more value ends above means and prefer the good to the useful. We shall honour those who can teach us how to pluck the hour and the day virtuously and well, the delightful people who are capable of taking direct enjoyment in things, the lilies of the field who toil not, neither do they spin.

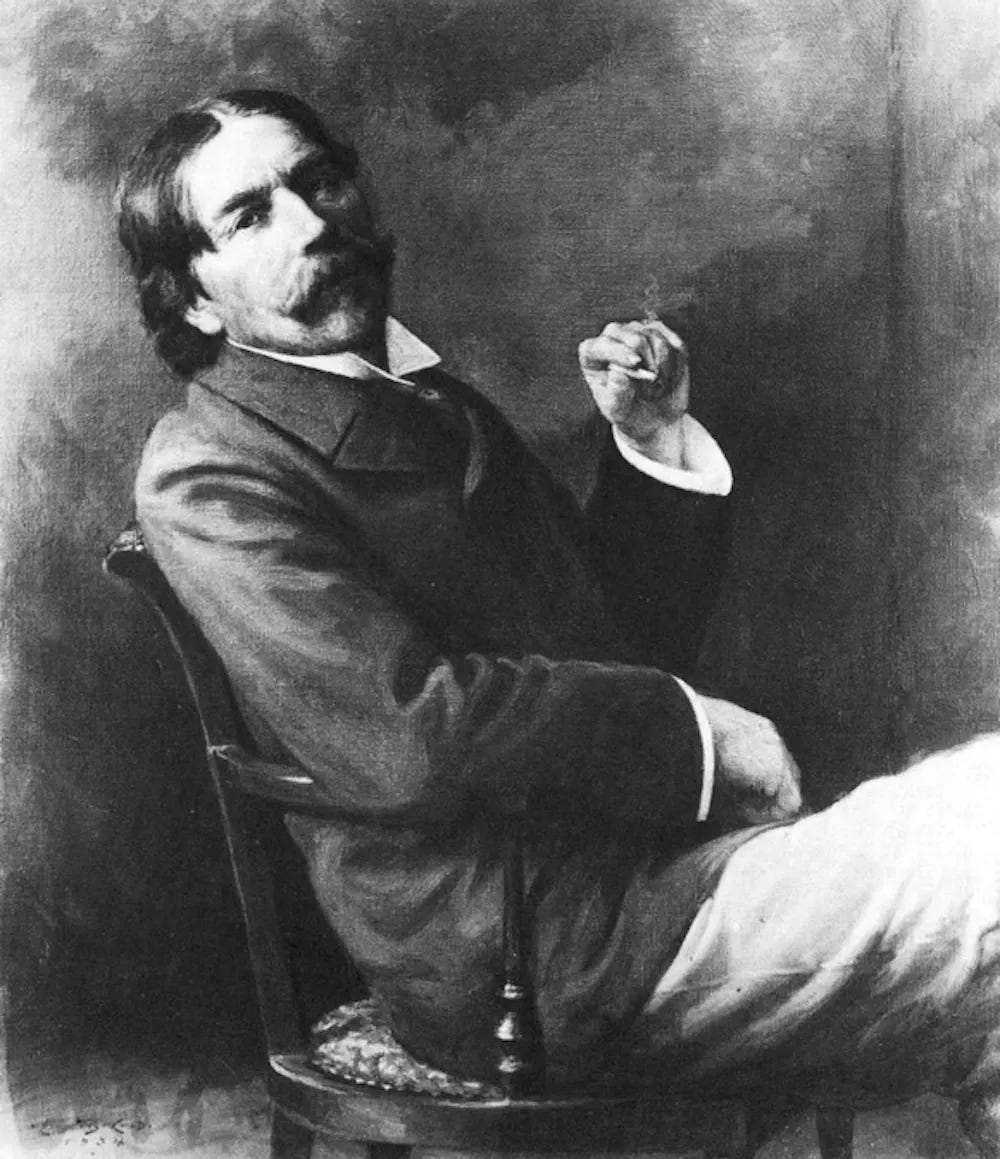

Bertrand Russell wrote in his 1932 essay “In Praise of Idleness” how everyone should now be a member of the leisure class:

Leisure is essential to civilization, and in former times leisure for the few was only rendered possible by the labors of the many. But their labors were valuable, not because work is good, but because leisure is good. And with modern technique it would be possible to distribute leisure justly without injury to civilization.

He thought that everyone should work fewer hours and have more time for leisure. The problem that he foresaw and that we see today is the issue of “positive idleness” such as painting or writing vs “negative idleness” which “ends up being the effect of work under the spell of consumerism and its consequent socioeconomic inequality.”

The pleasures of urban populations have become mainly passive: seeing cinemas, watching football matches, listening to the radio, and so on. This results from the fact that their active energies are fully taken up with work; if they had more leisure, they would again enjoy pleasures in which they took an active part.

We are all so worn out from our day at work that we basically flop down in front of the television. This is borne out by the statistics, which is why the artificial division of this category is distracting. The 1.5-degree lifestyle study includes “leisure activities performed outside of the home, e.g., sports, culture, entertainment, hotel services,” but in fact we spend the vast majority of our leisure time at home.

And why didn’t we get all that extra time that Keynes and Russell promised us? According to Benjamin Freidman, it’s because of inequality. Basically, all the gains from the increases in productivity went into the pockets of the rich. He quotes economist James Meade, writing in 1965, discussing why that leisure time never happened:

Meade instead thought “wages would thus be depressed,” as ever less labor was necessary for production. Correspondingly, an ever greater share of total income would go to the owners of the machines. In the absence of government-provided welfare on a massive scale, therefore, most of the workforce would be compelled to take whatever low-paying jobs they could get, presumably in the service of the machine-owners but not working with the machines. In Meade’s vision, “we would be back in a super-world of an immiserized [impoverished] proletariat of butlers, footmen, kitchen maids, and other hangers-on.” In today’s American context a half- century later, one might substitute gardeners, swimming pool attendants, personal trainers and home nurses.

Which brings us back to the concept of degrowth. As Jason Hickel wrote in Less is More , it’s all about distributing income and resources more fairly, liberating people from needless work, and “investing in the public goods that people need to thrive.” He continues, sounding a bit like Bertrand Russell:

Some critics worry that if you give people more time off they’ll spend it on energy-intensive leisure activities, like taking long-haul flights for holidays. But the evidence shows exactly the opposite. It is those with less leisure time who tend to consume more intensively: they rely on high-speed travel, meal deliveries, impulsive purchases, retail therapy, and so on. A study of French households found that longer working hours are directly associated with higher consumption of environmentally intensive goods, even when correcting for income. By contrast, when people are given time off they tend to gravitate towards lower-impact activities: exercise, volunteering, learning, and socialising with friends and family.

This is why leisure will become an increasingly important part of our carbon picture. In societies with strong social safety nets and less inequality, people have more leisure time and less worry. According to the International Labour Organization, “Americans work 137 more hours per year than Japanese workers, 260 more hours per year than British workers, and 499 more hours per year than French workers.”

The ideas of degrowth, sufficiency, and more leisure time all begin to look very attractive.

I try to write original content on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, and have been doing “bonus posts” from my archives or my books on occasional Tuesdays and Thursdays. The bonus posts are not a lot of work, but dealing with the comments is emotionally exhausting. For now I am going to turn off comments on the bonus posts.