OK, what should a green building look like?

It's going to be not too tall, not too big, not too glassy, boxy but beautiful, possibly Passivhaus, and it will have trees around it, not on it. Oh, and it is probably a bit boring.

After writing my last post, where I complained about an AI rendering of a “green” building, a reader made the obvious retort: What do I think a “green” building and a green city should look like? This is a subject I have been thinking about and discussing in my upcoming book, “The Story of Upfront Carbon.” The problem is that it may not make for pretty AI renderings if we are talking about building science rather than dramatic images. As Professors Jo Richardson and David Coley noted when discussing windows in Passivhaus buildings:

“Passivhaus only works if the right design decisions are made from day one. If an architect starts by drawing a large window, for example, then the energy loss from it might well be so great that any amount of insulation elsewhere can’t offset it. Architects don’t often welcome this intrusion of physics into the world of art.”

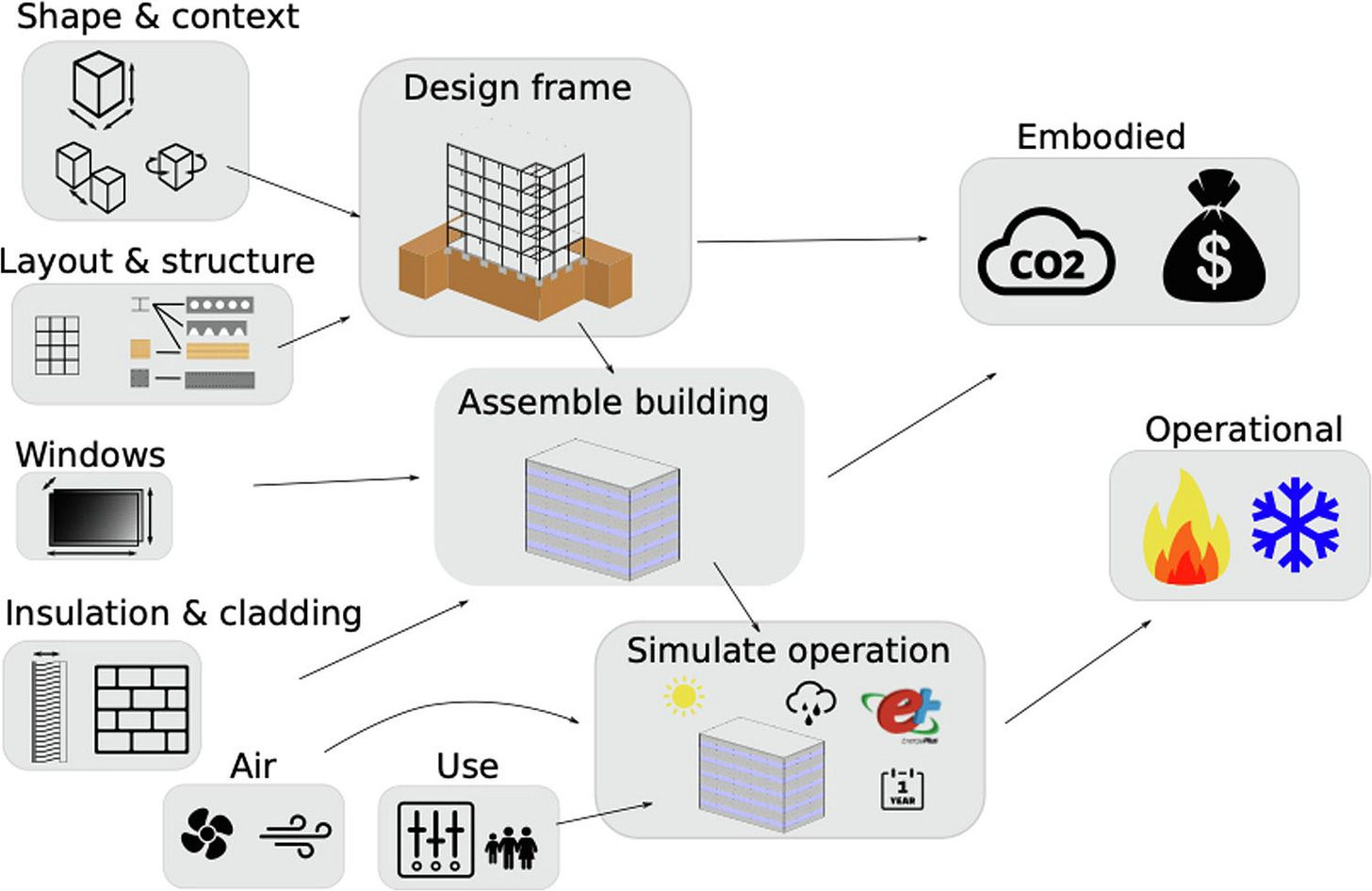

If we are going to be driven by physics and building science rather than art, a good place to start might be the research by H. L. Gauss of the University of Cambridge. His team built what I called a “magic box” of a program where they could adjust input variables:

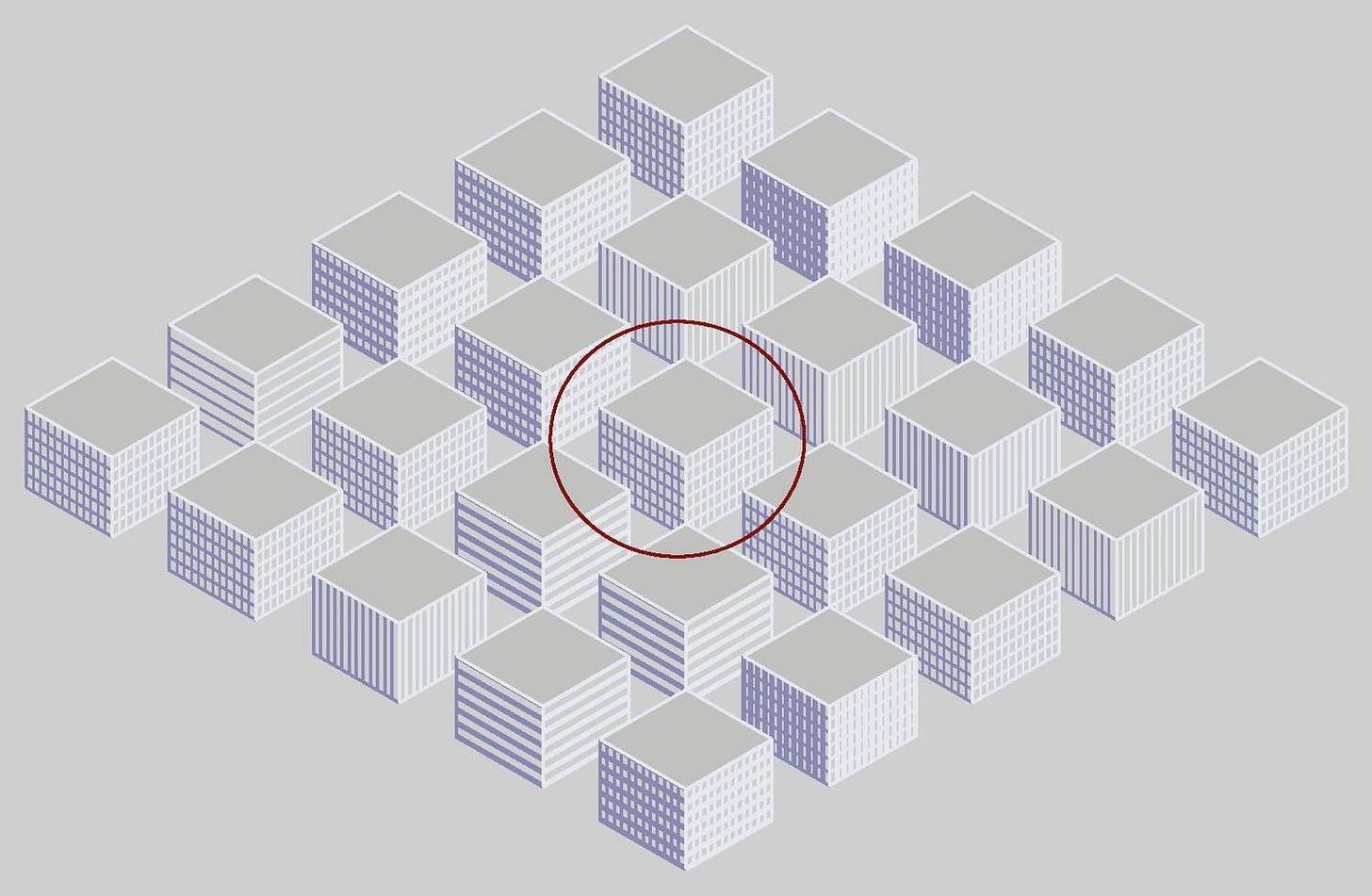

“A wide range of sizes and shapes of buildings are considered by varying the area per storey, aspect ratio, number of storeys, and height per storey. The building orientation and the distance to neighbouring buildings, which are assumed to be of the same shape and size are further considered to model different urban contexts. Structural frames are designed for a range of column spans, frame types, imposed loads, and are optimised for either cost or carbon.”

There are so many knobs to turn here, with input variables for a building's shape, size, layout, structure, ventilation, windows, insulation, air, and use for residential and office multi-story buildings, across different climates. For embodied carbon, they use "cradle-to-completion," which is our definition of upfront carbon emissions. They modelled a simple building without basement or service cores.

In my upcoming book, I did a play on Louis Kahn and his conversation with a brick:

You say to brick, “What do you want, brick?” Brick says to you, “I like an arch.” if you say to brick, “arches are expensive and I can use a concrete lintel over an opening. What do you think of that, brick?” Brick says: “I like an arch.”

So I said to the green building, “What do you want to be?” With Gauch’s magic box interpreting, we learn:

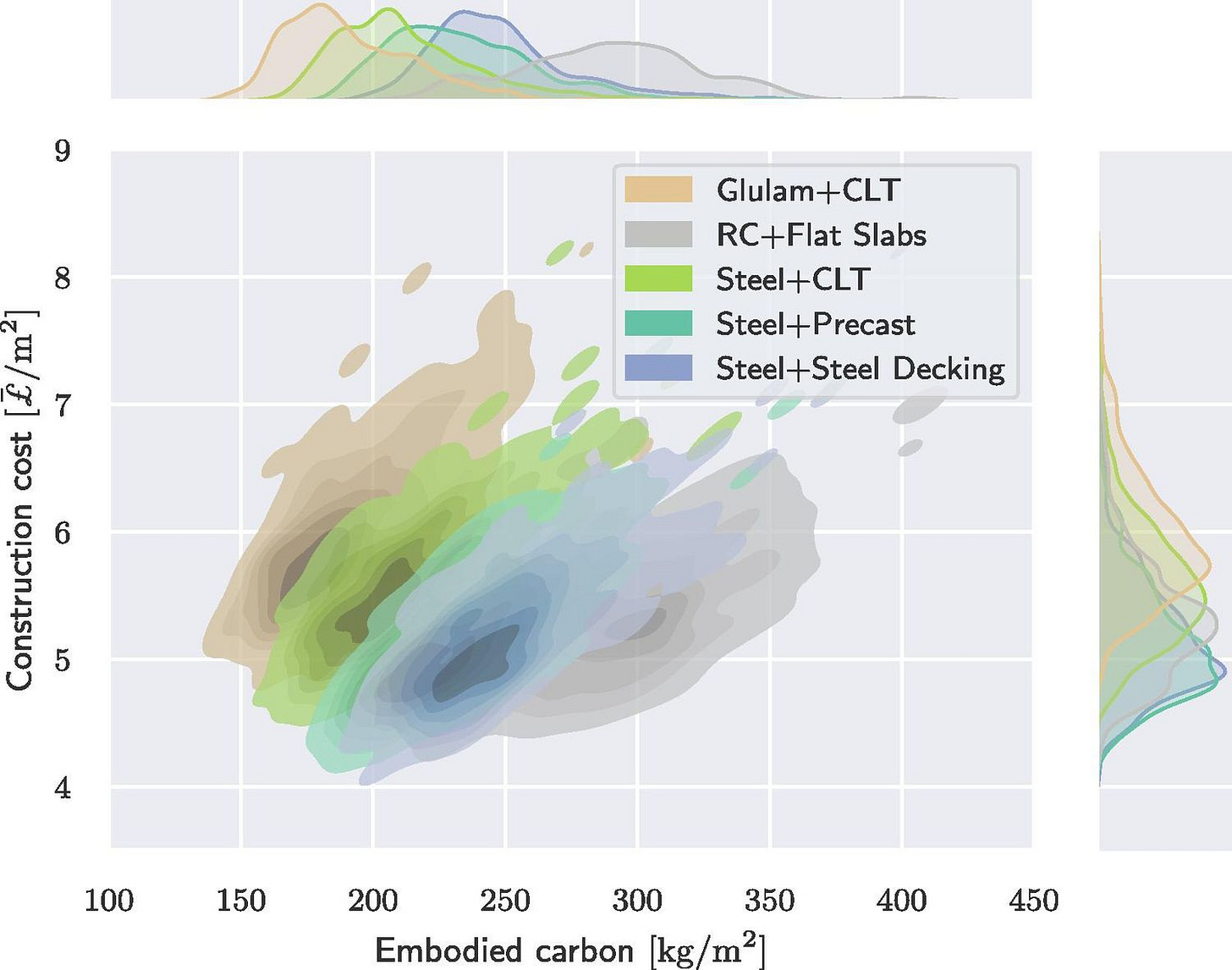

Buildings want to be wood and renewable.

Mass timber comes in with the lowest upfront carbon, but not the lowest cost. I asked Gauch why there wasn’t an input for light wood framing, and he told me, "We have not included light timber frames in our study. It is not common in the U.K. to build larger buildings that way, but a comparison might be an interesting study to do!" It would have made a big difference in the cost because it uses about a quarter as much wood as mass timber.

Buildings want to be short.

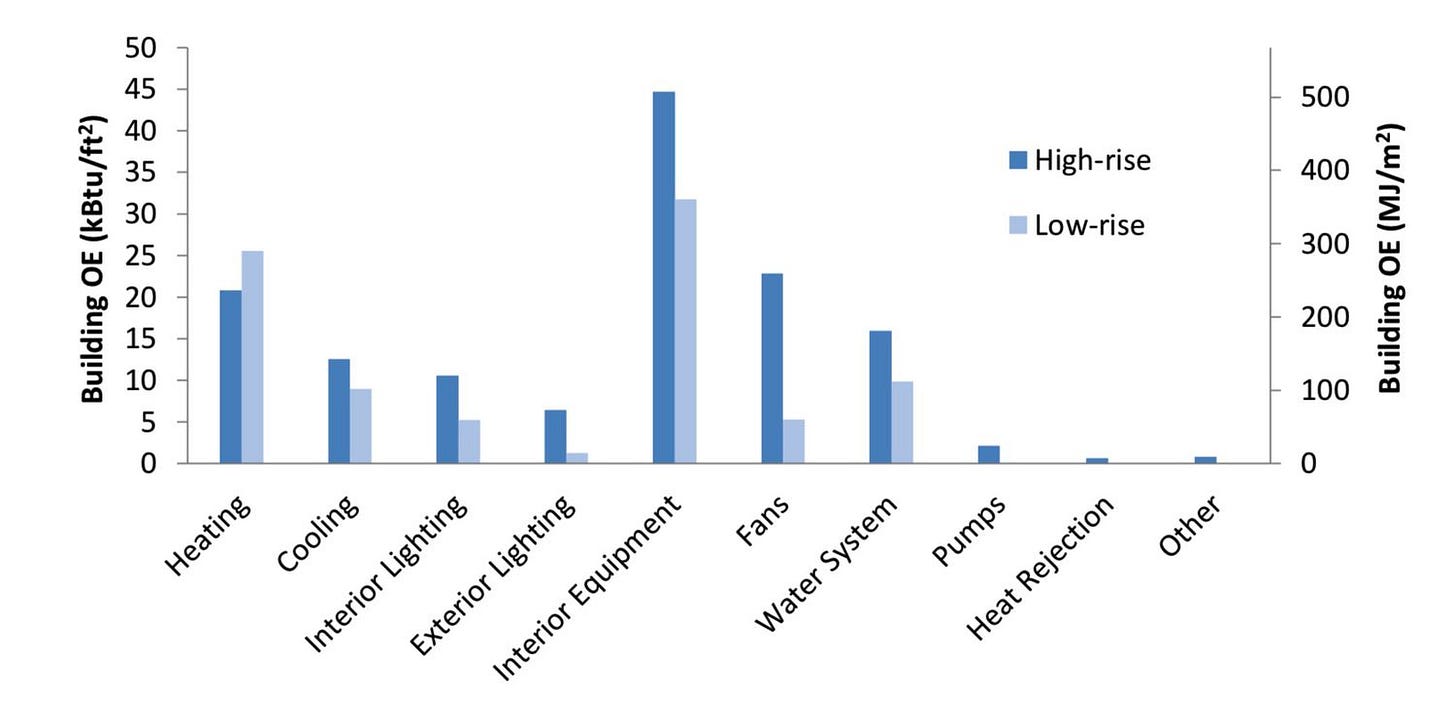

Being short, I liked this. The Goldilocks spot for upfront carbon is about six stories. There are practical limits to how high you can build in mass timber, and six stories are usually the limit for light wood framing that’s common in North America and Scandinavia. That’s why architect Piers Taylor told the Guardian: “Anything below two storeys and housing isn’t dense enough; anything much over five and it becomes too resource intensive.”

Everything gets more expensive when you go tall, not just structure. Plumbing, structure, elevators, everything except land cost per unit, which is why developers want to keep piling on the floors. And for those who say we need tall buildings to house everyone, we’ll always have Paris to show us how to do density.

Buildings want to be boxy.

The study finds that compactness cuts heating and cooling in half and reduces upfront carbon and construction costs. This flies in the face of contemporary practice, where architects use computers and parametric design to increase complexity and surface area. In our homes, we see gables and jogs and bump-outs, when in fact, we should all be following architect Bronwyn Barry’s hashtag #BBB: Boxy But Beautiful.

Buildings want to have more wall than window.

This is a problem for architects, who design windows more for their aesthetics than for their usefulness. Gauch writes in the study:

Decisions concerning windows are most influential for heating and cooling loads, especially the window-to-wall ratio. Whilst higher window-to-wall ratios decrease all three efficiency metrics, windows with lower U-values (triple and quadruple glazing) entail higher costs. This suggests a non-negligible trade-off between energy efficiency and construction costs.

We spend so much time yammering about energy efficiency and insulation, but Gauch found that building form plays a huge role:

"Our results show that building size and shape as well as the frame type and layout are amongst the most significant variables determining embodied carbon, construction cost, and heating and cooling loads of a building... We have shown that it is difficult, but possible, to achieve designs with near-zero energy demands for heating and cooling in many climates. Yet only through a combination of mechanical ventilation with heat recovery, compact building forms, limiting the window-to-wall ratio, and small solar heat gain coefficients can designs satisfy, or get close to, Passivhaus standard requirements."

I wrote about this on Green Building Advisor: Rethinking Window Size.

So when I go back to the question of what a green building should look like, it looks a lot like the LILAC affordable ecological co-housing project, by White Design and built out of Modcell prefabricated straw panels. It’s not as flashy as an AI rendering, but it twists every knob on the magic box, with low carbon materials, boxy forms, not too many windows and mechanical ventilation heat recovery. They could put green roofs on them but did solar panels instead.

None of this is to disparage putting green stuff on buildings. Cornelia Hahn Oberlander and Arthur Erickson created one of the most beautiful spaces I have ever been in at Vancouver’s Robson Square. Green roofs and living walls have many benefits, but significantly reducing upfront and operating carbon emissions is not among them.

I have spent days asking search engines to show me green buildings, and they are all tall curvy things covered in plants that make Vincent Callebaut look plausible and talented. But as I complained after seeing yet another Bjarke! Ingels building:

If we are ever going to get a handle on our CO2, we are going to see a lot more urban buildings without big windows, without bumps and jogs. Perhaps we might even have to reassess our standards of beauty.

Lots of people are buying them now where they are offered, and if you think you don't have central government planning in the USA, you are dreaming.

Maybe a start would be to stop calling them green buildings ... Poor AI is wondering "why do these humans keep asking for buildings that are the colour green". Just a thought - nice post. I love the boxy but beautiful phrase.