My TMU Sustainable Design students on how to fix the world

I think I learn more from them than they do from me.

For about a dozen years, I have taught a one-term course on Sustainable Design at Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU, formerly Ryerson University). It started in the School of Interior Design but has expanded to include students of photography, urban design, fashion, and journalism from the Creative School. Teaching sustainable design is tough; it is constantly changing. Who was teaching about embodied carbon a dozen years ago? It’s not like teaching Latin; Every year, you have to keep current and start over.

Then there is the format. Having an old white guy standing in front of a class lecturing is so tired. The only things that have changed since 1233 in Bologna are that now I have PowerPoint, and the students have phones. During the pandemic, I taught by Zoom and looked forward to being in the classroom again, but about half of the students don’t show up, and half of the ones that do have their noses in their computers. With only ten lectures, I barely get to know them.

Then, there is the idea of teaching sustainable design to third and fourth-year students in a one-term optional course. It should be mandatory in the first year. I have had students tell me they would have done different work had they learned about it earlier.

Then there is the lecture hall; the class is very popular, and there isn’t a big enough classroom in the School of Interior Design, so I am shuffled all over campus. At least this year, I was in the School of Architecture, but the lecture hall doesn’t meet standards for air changes, and my little CO2 meter often pushes 1400 PPM. I tested for Covid every week.

Then there is the grading. I have 136 students and do not have a teaching assistant, so I have to do everything myself. It took a week of 10-hour days to get through the final exam, and I couldn’t see straight by the end of it.

So why do I do this? It’s not for the money; I suspect I would earn more per hour flipping burgers. It’s not for the camaraderie; I have barely met other staff because I am never in the school itself. It’s not for academic glory; I used to have “Adjunct Professor” on my email signature line and was informed that this was wrong; I am a mere “Contract Lecturer.”

Ultimately, it is for the satisfaction I get from many of my students' work, particularly in the final exam. It becomes clear that they have been listening and learning, and many tell me they have been inspired. A few have said it changed the direction of their lives and switched courses to the sustainability sector.

And sometimes, I feel that I am learning as much from them as they are from me.

Take this year’s exam, which I titled “How to Fix the World-” if there is one thing I am trying to get across, it is that while our problems are dire, there are solutions. If they are going to be designers, they must be at the forefront, understanding the issues and selling the solutions.

I have a short attention span and die if I have to read a long paper, so I broke the exam into small bits. I gave the students 16 topics running the gamut from work, water, fashion, food, and education. I asked them to define the problem (a narrow column because I only expected a few words) and propose a solution for any six of the 16.

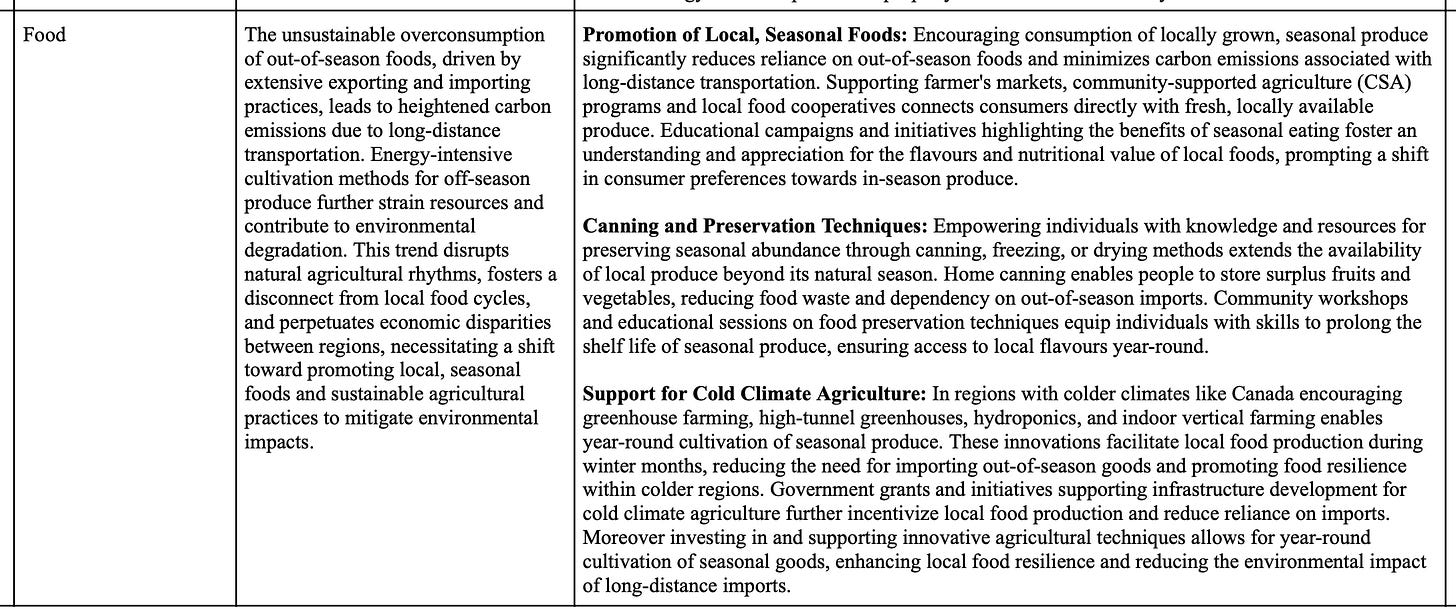

The answers were interesting, intelligent and often better than I could have written. Here’s an example of the different kinds of answers I got for the problem of food, like this basic summary of the solution (less meat, grow your own, local and seasonal)

Others like Zooey gave me lists.

Kate looked at the footprint of delivery apps, something I had never considered.

Caitlin looked at food waste.

You’ll see a lot of Rosie, who would list three or more smart points on each subject. This could well be the outline of my course next year. They are not just parroting me; Rosie talks about cold-climate agriculture, which I never mentioned. Put these all together, and you have an excellent introduction to the problem of food.

Clothing and Textiles are a huge issue, 10% of global emissions, bigger than concrete and twice that of aviation. I knew nothing about this and ignored it in my book. So I was excited to have a few fashion design students; some knew all about it, and the others were shell-shocked. Most of the students concentrated on fast fashion.

However, materials mattered too.

In transportation, it was clear that my riding in to class (literally into the classroom and parked at the back, I want them to see it!) in the rain and cold had an influence, and almost every answer discussed cycling infrastructure.

Here’s Rosie again, making many points but not forgetting about my beloved e-bikes.

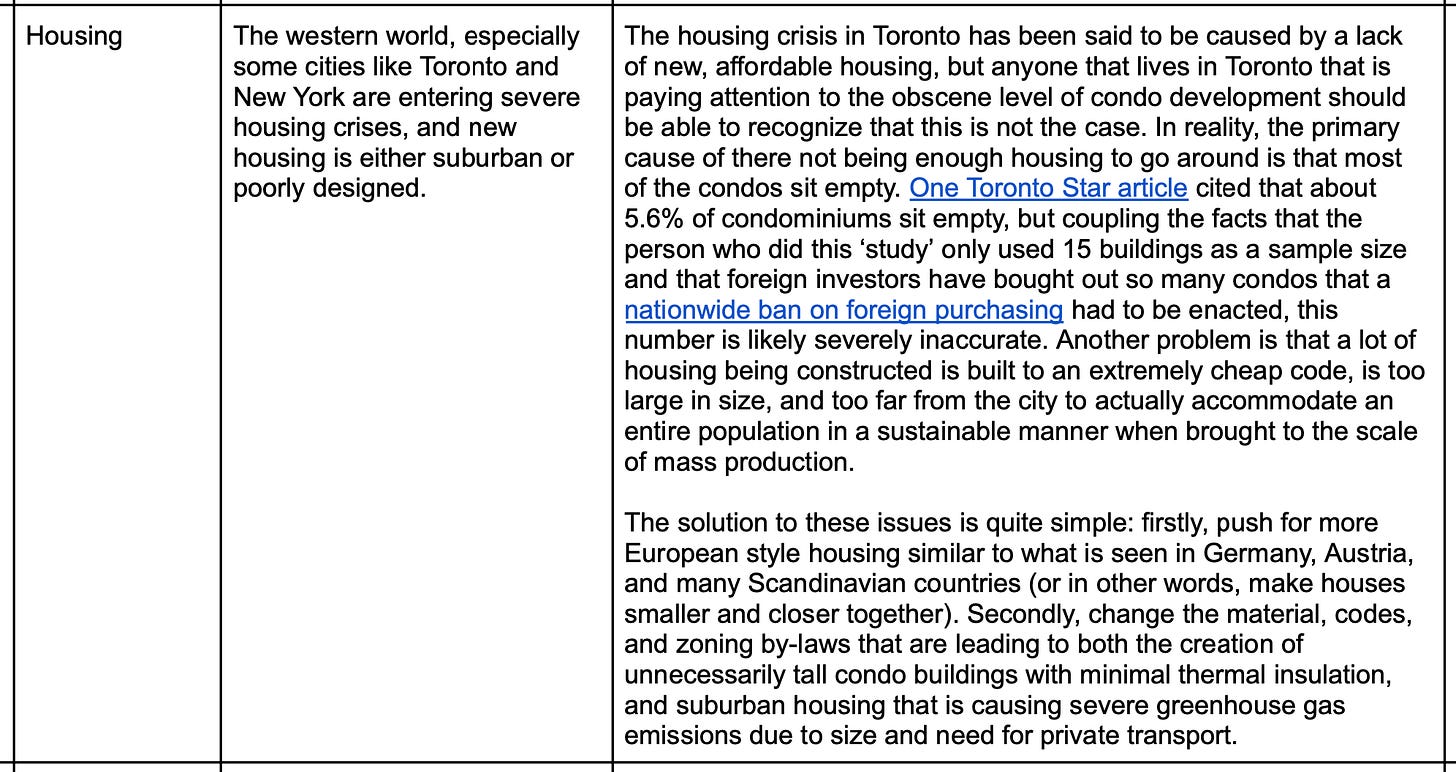

In housing, my message got through: go for the Goldilocks density, go Passivhaus, learn from Germany, Austria and Scandinavia, and stop with the too-tall condos.

Similarly in tech, the issue was that of frequent upgrades and planned obsolescence.

Some of the sixteen topics are there because I just wanted to hear what students had to say about issues that I have no answer for, such as how to teach about carbon and climate. When do you start? I got very few answers, but I liked Alesia’s: “Integrating comprehensive climate education into formal school curricula is fundamental. This includes educating students about the science of climate change, its consequences, and the role of human activities.”

The least answered and probably toughest category is equity, how people in rich countries are emitting so much carbon, and the poor are suffering the consequences. This is an issue one could spend a whole term on; Juliana’s answer is two classes right there. This is the lecture where I get a bit bolshy and eat-the-rich. This is the one that will be hardest to solve.

In the end, I do not get a recipe for how to fix the world. But I have a lot of ingredients and a lot of directions. Just putting this post together has me thinking about another six posts I could write. There is a book in it somewhere.

Every year, as I am marking papers, I think I should stop this; perhaps it is all too much work, and I should step out of the way for someone younger with new ideas. But as I told my students in the first class, “Don’t rely on ChatGPT. Its database only goes up to 2021, and almost everything we are talking about is newer than that.” I am still on top of new ideas and even generating a few of them, often because I am challenged and inspired by my students. I’ll be back.

You do them no dis-service as an "old white guy" sparking their creative minds! Riding into class on your bike certainly catches their attention and gives you some immediate credibility on the subject at hand. Successfully challenging a large group of kids w/ diverse backgrounds and different majors to just think about the multitude of impending problems, and then come up with their own creative ideas is a great accomplishment. Kudo's Lloyd!

“Integrating comprehensive climate education into formal school curricula is fundamental. This includes EDUCATING students about the science of climate change, its consequences, and the role of human activities.”

The caveat, of course, is whether or not you're going to educate them or indoctrinate them. (I'd suggest it's the latter and not the former.) How is it that so many Nobel laureates in physics, atmospheric sciences, geology, and other academic disciplines change their tune on climate change once they retire? Is it because they've lost their minds, or is it that they no longer have professional retribution to fear? Personally, I'd suggest your students read everything about climate change using their critical thinking skills—but that's something in short supply amongst the younger generations.

"The answers were interesting, intelligent and often better than I could have written." That's probably because much of what was submitted was likely done via ChatGPT. I mean, just looking at the responses given, it reads like it was churned out by an A.I. bot, especially if you're only requiring them to provide a PDF document as a final answer.

Lloyd, you talk about "sustainability" frequently, but I don't think you've ever properly defined it in context of feasibility, costs, or the balance between sovereignty, resource allocation, population, need, and local/regional environment. I think that it's vitally important to define sustainability in terms of context for all those things, because as I alluded to in another post, dealing with climate change is not just a series of individual silos to be addressed irrespective of each other.

When I was going through college I took a single-semester course on ethics; we explored many facets of what ethics encompassed and how it was demonstrated, and ultimately on the last day of the class our professor revealed to us his definition of what ethics meant, and it goes like this:

"Ethics means doing the MOST good for the MOST people MOST of the time."

Notice he didn't phrase it as an ***absolute***, because no matter what is done in life there will be winners and losers; some will have more than others, whether by sheer luck, work ethic, or design. My throwing out an eggplant tonight because it was going fuzzy will not, in any capacity, affect the resolution of someone's hunger pangs on the other side of the planet tonight. Likewise, merely suggesting we should shun meat and eat more of a plant-based diet overlooks two very important things: (1) most of the world's meat is grown on land that is NOT conducive for growing vegetables or fruit, and (2) meat can be processed, frozen, and transported across the entire globe without ANY degradation in quality or quantity. The same cannot be said about fresh vegetables and fruit, which is simply a function of the perishable nature of said consumables. The **ethical** thing to do is to fully utilize what you buy and thus limit waste, but waste will be inevitable to some degree no matter what. But suggesting that a resource like beef and lamb should be severely restricted belies the resource utilization of the land itself for an alternative.

So how do you get a nation with few natural resources to grow more of their own food? In modern Western nations, we have the good fortune—again, by design or luck—of being able to produce vast quantities of food that can be shipped to all nations around the globe. Which then begs the question, should the nations **without** those resources have ever been allowed to have as many children as they did, forcing them into unsanitary and unsafe conditions, rife with poverty, crime, and hopelessness, or would it have been more ethical to allow them to become dependent on foreign aid to artificially prop them up above the carrying capacity of the land they live on?

That's an existential question, besides being a rhetorical question. My point is, "sustainable" is not a catch-all term that only some people (read: developed nations) must ascribe to in practice, or that can even be easily defined at the individual level, much less collective, because of how complex the practice of living is for all of us. If I have a lot of money but lead an austere lifestyle, what rewards do I get for doing so? Anything tangible? And if not, then why should I be ridiculed for indulging in activities or consumerism that provides personal enjoyment and enrichment of the soul—and which CANNOT be distributed equally amongst the other 8 billion inhabitants of the planet? Like I pointed out above, my failure to eat that eggplant before it went fuzzy will, in no shape, way, or form impact the life of someone else somewhere else—whether that be next door, in the next county over from mine, next state, or across the ocean.

You wrote: "The least answered and probably toughest category is equity, how people in rich countries are emitting so much carbon, and the poor are suffering the consequences ... [t]his is the lecture where I get a bit bolshy and eat-the-rich." Well holy shit, that comes as no real surprise to anyone that you get "bolshy" about carbon equity. But then again, you've ***always*** been a watermelon—green on the outside, communist red on the inside—except you've now stopped pretending you **aren't** one.

Here's the thing: **YOU** don't get to tell me WTF to do with **MY** money, or how I must live **MY** life, any more than I get to tell you what to do with **YOURS**. You want to live a life of austerity, shunning many of the things that make modern Western society a pleasure that literally millions risk their very lives to attain? Great, that's YOUR choice, and more power to you and your misguided belief that it's going to mean a squirt of flea piss on a rat's ass to saving the planet, because it's not—that was the false equivalence so often promoted over on TreeHugger, that somehow YOUR personal decision to live a life of lesser means translates into "saving" the planet, and that by extension, I should thus be forced and coerced to do the same. As I said back then to those idiots who espoused that mindset, "F—k you and the horse you rode in on." It ain't happening, ever, and not just because it runs afoul of the ideals of personal freedom and individuality—it also runs afoul of basic human nature.

You wanna eat the rich? Great—but if you had the ability to exercise your fascist dreams to make that happen, where would investment come from for innovative minds to create the next true breakthrough in technology, science, agriculture, transportation, medicine, and the like if meritocracy and rewards are not part of the equation? I'm not saying you should kneel and kiss the ass of people who are well-to-do (or even obscenely rich) but at the same time, what THEY do with THEIR money and time IS OF NO CONSEQUENCE TO THE PLANET, NOR OF REQUIRING INTERVENTION BY YOU OR ANYONE ELSE TO DICTATE TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF HOW THEY UTILIZE THEIR PERSONAL ACHIEVEMENTS. We saw how the Soviet Union collapsed under the weight of its own disincentives to meritocracy and innovation; are you suggesting that for the good of the planet Western society should eschew modern life and embrace a third-world lifestyle? Good luck with that if that's your belief, because that's neither ethical nor reasonable.

Once again, you've proven to me that "sustainable" is a feel-good term that watermelon communists love to promote but can ill-define—and even more poorly demonstrate (COP28, anyone?) because it relies on the twin tenets of coercion and prohibition to achieve its goals.

Good health and happiness to you in 2024; the gloves are off early this year.

Good health and good fortune to you in 2024, Lloyd.