Many are at Stage 5 of climate denial: "It's too late." It's not.

An excerpt from my book, The Story of Upfront Carbon, about doomerism and its discontents.

My recent post, ‘In Defence of the Doomer David Suzuki,’ sparked a lively discussion about doomerism here and on LinkedIn. I find it hard to be a doomer when I’m entertaining my six-year-old granddaughter and thinking about her future; I want to believe that we can make the world livable for her and her sister. I also find it hard to find time to write a post when I would rather take her hiking and rock-hunting, so here’s an excerpt from my book, The Story of Upfront Carbon, where I discuss doomerism.

OK Doomer

About a decade ago, as the IPCC released its fifth round of reports, climate journalist Dana Nuccitelli described the five stages of climate denial . They were:

Stage 1: Deny the problem exists. We are well past that now, although a few flat-out deniers still exist in comments sections of newspapers.

Stage 2: Deny humans are the cause. There are still a few of these about, still blaming sunspots and claiming that the earth goes through natural cycles.

Stage 3: Deny it’s a problem. More CO2 means more plants! More warming means more Canada!

Stage 4: Deny we can solve it. It’s too expensive; it will hurt the poor; it will trash the economy. This is the popular one right now with Lomberg and Shellenberger.

Stage 5: It’s too late. When Nuccitelli wrote these, he noted that “few climate contrarians had reached this level.” Today, the world is full of what author and climate scientist Michael Mann called “doomists:”

Exaggeration of the climate threat by purveyors of doom—we’ll call them “doomists”—is unhelpful at best. Indeed, doomism today arguably poses a greater threat to climate action than outright denial. For if catastrophic warming of the planet were truly inevitable and there were no agency on our part in averting it, why should we do anything? Doomism potentially leads us down the same path of inaction as outright denial of the threat. Exaggerated claims and hyperbole, moreover, play into efforts by deniers and delayers to discredit the science, posing further obstacles to action.

Hannah Ritchie of Our World in Data recently raised the same point, suggesting that doomers were worse than deniers.

Climate deniers want us to choose to do nothing; that it’s not a problem and doesn’t require any action. Climate doomers tell us that we don’t even have a choice to do something; we’re already screwed and it’s too late to act. Follow either and we end up in the same place of inaction. That’s a place that we can’t afford to be.

Author Jonathan Franzen is a key “doomer,” as I prefer to call them, telling Australian radio that “We literally are living in end times for civilization as we know it. . . . We are long past the point of averting climate catastrophe.” Brynn O’Brien, executive director of the Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility, responded and is quoted in the New Statesman:

The only people who fall for it are rich white people who think they will be spared until everyone and everything else is gone. His position is unscientific, morally careless (at best) and politically blinkered. Things are very bad and will get much worse. But scientifically and politically, there are still so many choices we can and must make to avoid all-out catastrophe, to avoid “end times.”

The doomers were out in force when the annual Emissions Gap report from the United Nations Environment Programme was released just before COP27. Everyone piled on one sentence: “As climate impacts intensify, the Emissions Gap Report 2022 finds that the world is still falling short of the Paris climate goals, with no credible pathway to 1.5°C in place.” They all then proceeded to totally ignore the sentence which directly followed: “Only an urgent system-wide transformation can avoid an accelerating climate disaster.”

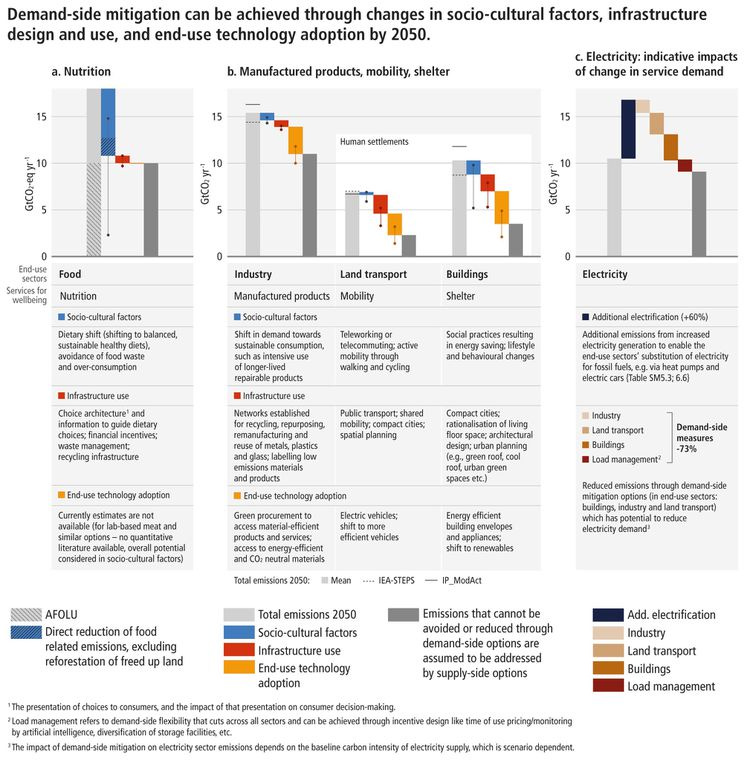

The report looks at how to deliver this transformation through action in the electricity supply, industry, transport and buildings sectors, and the food and financial systems. The report then laid out what UNEP Executive Director Inger Andersen called a “root and branch transformation” of our economies and societies, with many of the same “demand-side mitigations” called for in the IPCC report.

The emissions gap between where we are and where we have to go can be closed with reductions in demand, living in smaller spaces, switching to lower-emitting modes of transport such as bikes and public transit, eating less meat, and building better buildings. These are again all about sufficiency.

But the doomers have a point when they quote the report. In his book I Want a Better Catastrophe, Andrew Boyd tries to put the best spin on being a doomer, suggesting that people and organizations may be putting their best spin on bad news. Inger Andersen calls for a “root and branch transformation,” when she knows it is not happening. Is she just telling people the most hopeful version of the truth, as Boyd suggests? Boyd describes the process:

Try to be as positive and pragmatic as you can be. Tell the best possible version of events. Focus on the promise and potential of the moment. And fight like hell and hope for the best.

This is the position I have taken: that we know what to do. Otherwise, I wouldn’t have much of a book here. It’s hard sometimes when we see so little progress. As I write this, I am trapped inside a cabin in the woods because the air outside is toxic, full of smoke from forest fires in Quebec. But I am still positive and pragmatic. I am not alone; Professor Kevin Anderson of the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, perhaps one of the direst climate experts, said in a recent interview:

We are going to fail. We are going to go to 3 or 4 degrees Centigrade of warming, and we will have to live through or die from all of the repercussions that will have. That is a terrible prospect and one that I think we have to try everything to avoid. But the message of hope, if there’s any thread of hope in this, is that it is a choice to fail . . . we can choose a different way out of this. Now whether we can still hold to 1.5, it looks incredibly unlikely to me. But incredibly unlikely doesn’t mean it’s impossible. It is only impossible if we don’t try.

And that is why we are here, to fight like hell and hope for the best. And as the UNEP Emissions Gap report notes, we have to do it now, with every decision we make, to avoid what’s called “lock-in”:

Decisions made today can define emissions trajectories for decades to come. For example, a building lasts 80 years on average; a coal-fired power plant 45 years; a cement plant 40 years. Pipelines and gas connections create decade-long dependencies. Interventions can also lock in behavior and policies that reinforce incumbent systems. Actions today that lock in a high-energy and high-carbon future for decades must be avoided, including avoiding new fossil fuel infrastructure for electricity and industry, car-centered city or regional planning, and inefficient new buildings. These actions do not always result in immediate emission reductions, but are fundamental for the long-term transition.

Lock-in is disastrous when we are talking such small numbers remaining in the carbon budget and so little time to reduce emissions. But lock-in doesn’t just happen at the industrial level with highways and cement plants—it happens at the personal level with the decisions that we make in our own lives. In 2014, when renovating my own home, I bought a new gas boiler to pump hot water to our hundred-year-old radiators. Heat pumps were just too expensive at the time, so I locked myself into gas. People do this every day when they buy new cars or new houses in the suburbs; they are locked into fossil fuels for years to come.

Every giant new pickup truck I see in my neighbourhood is lock-in writ large. It seems there should be a Stage 6 of climate denial: “It’s happening, it’s real, it’s someone else’s problem, it is too inconvenient, and I don’t care.”

This is why socio-cultural and behavioural change as well as demand-side mitigation are so critically important. Just as every kilogram of carbon we add to the atmosphere is subtracted from the carbon budget, every new lock-in ensures that we keep subtracting it for years to come.

Special offer!

I do not want to put up a paywall on this site, but it provides a meaningful portion of my income. So here’s a limited-time offer: I will send a signed copy of the print edition of “Living the 1.5 Lifestyle” to anyone in the USA or Canada who signs up for a one-year subscription (C$50, cheap at about US$35 ).

I really appreciate the information you share in these posts! And I completely agree about the big pick ups - I am surround in my town with the extra large trucks whose drivers add all the stupid stuff to them that seem to make make them even worse for us pedestrians on the sidewalk. And don’t even get me started on the ones who remote start their trucks in back corners of my apartment parking garage, where there’s no ventilation, and leave them running for a long time before they bother to come back down and get in them!

However much damage has already been done, we still can still significantly ‘flatten the curve’ with meaningful action.