Looking back at Bjarke Ingels' Amager Bakke

The incinerator with a ski hill that "under a decade since opening, has gone from green icon to bête noire."

Almost everybody loves Bjark Ingel’s Amager Bakke, (also known as ARC) the world's most photographed incinerator — sorry, I mean waste-to-energy (WTE) plant — in Copenhagen. I toured it in 2017, and shortly before it was complete, it was burning garbage, but the ski slope and the climbing wall had not yet been installed. The numbers were impressive:

It's a lot of garbage; in 2015 ARC converted 395,000 tonnes of waste into 901,000 MWh of energy, of which 766,000 MWh was heat, equivalent to the consumption of 150,000 homes, and 135,000 MWh of electricity. It uses a "wet" smoke cleaning system that will remove 85% of nitrous oxide, 99.9% of hydrochloric acid, 99.5% of sulfur.

What it doesn’t remove is Carbon Dioxide. Burning waste puts out more CO2 per tonne of garbage burned than coal, but half of it “doesn’t count” because as the International Energy Agency explains, "burning fossil fuels releases carbon that has been locked up in the ground for millions of years while burning biomass emits carbon that is part of the biogenic carbon cycle." Burning food waste or IKEA furniture is fine. Plastics, on the other hand, are treated as fossil fuels that took a short side trip through your water bottle.

Denmark is particularly addicted to WTE. I wrote in a 2021 post:

Amager Bakke is purported to be the cleanest WTE plant in the world. But it was an expensive plant to build, and Denmark has 22 others that provide district heat, as well as electricity, to communities. According to Politico, Denmark imported a million tonnes of waste in 2018 from the United Kingdom and Germany, essentially transferring emissions from one country to the other, to keep everything running.

Tim Smedley of Prospect Magazine recently visited what is now commonly called “CopenHill” and was unimpressed. He says it was deserted and smelled like garbage. “The unmistakeable scent of bin lorry seeps in.” He claims it has, in “under a decade since opening, gone from green icon to bête noire.” He points to a report by Zero Waste Europe which notes that the plant was controversial from the start, with many people demanding better recycling and reduced consumption.

“ARC has been a technical and financial fiasco, characterised from the outset by poor judgment that ignored the advice of experts, and project management that contradicts the municipalities’ own waste management and climate plans. As a result, Copenhagen now has an incinerator plant that is double the size needed and that may need to import more and more foreign waste if it is to keep running.”

Smedley concludes that it is an empty, smelly, anachronism.

“As I exit the lift at the bottom of CopenHill, a handful of after-work skiers arrive. I stay to watch them carve down an artificial slope pockmarked with grass and moss. Above our heads, huge chimneys emit endless clouds of steam and CO2. Our clothes will smell of bin juice when we get home. A prominent sign at the slope’s entrance reads “NO SMOKING OR VAPING. Only our chimneys are allowed to vape.”

In the USA, the fossil fuel and petrochemical industry has been promoting Waste to energy for years. Dow Chemical and the Keep America Beautiful people peddled hilarious “energy bags” at one point to keep the single-use plastics gravy train running. I noted that it was even more insidious than recycling: “It wasn't enough that the industry trained us to feel good about picking up their garbage; now they are convincing us that incineration is a virtue, that it is actually part of the circular economy.”

Amager Bakke, ARC, Copenhill, whatever one calls it, was fundamentally a mistake, as are most WTE or as they call them in the UK, Energy from Waste (EfW) plants. In the UK, according to the Climate Change Committee, “EfW plants have been one of the main sources of rising emissions in the UK in recent years and they will need to be decarbonised for the UK to reach Net Zero.” Even Denmark is backtracking; according to Yale Environment 360:

Pushing to meet ambitious carbon-cutting goals, Danish lawmakers agreed last year to shrink incineration capacity by 30 percent in a decade, with the closure of seven incinerators, while dramatically expanding recycling. “It’s time to stop importing plastic waste from abroad to fill empty incinerators and burn it to the detriment of the climate,” said Dan Jørgensen, the country’s climate minister.

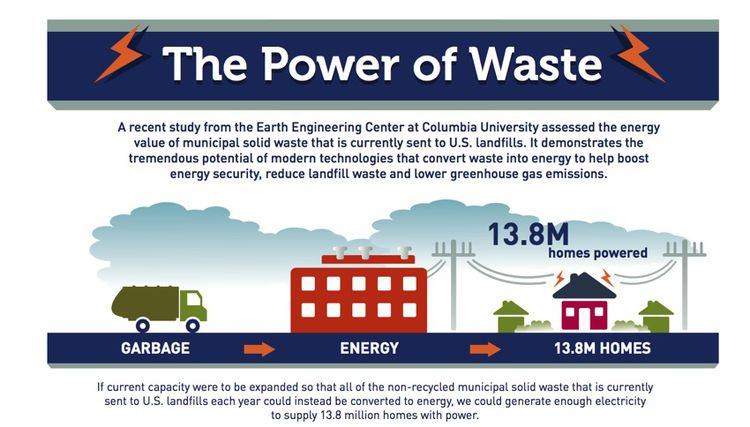

The American Chemistry Council has been pushing WTE in the US to “boost energy security.” I suspect we will be hearing a lot more of this in the next few years; it keeps those petrochemical companies pumping out single-use plastics. They say “It’s not waste; it is solid energy.” But as I wrote a couple of years ago,

The unfortunate truth is that recycling is broken, landfills release methane, and even the cleanest waste-to-energy plant pumps out CO2. Aiming for zero waste is really the only option we have, now that we know that pretty incinerators topped with ski hills won't save us.

I spend a lot of energy bashing Bjarke for his overly expensive and complicated designs. Amager Bakke may be his greatest monument: a white elephant and a stranded asset, but hey, what a fun climbing wall and a ski hill with a great view.

A few years back, I was interviewed for an article on CopenHill inThrillist (https://www.thrillist.com/travel/nation/copenhill-copenhagen-ski-slope-power-plant). While lauding the fact that it made for unusually interesting municipal design, I also said "One can debate the merits of waste-to-energy. Yes, it makes energy from garbage, but it’s still incinerating it and spewing not-so-great things into the air, even when it’s called clean waste-to-energy. And wouldn’t it be better to not make so much garbage in the first place?”

I've since taken to calling waste-to-energy "waste incineration with a side of energy."

There is no solution to managing solid waste other than not producing it in the first place. I'm on our little town in Maine's solid waste committee. One fact that surprised me is that close to half of municipal solid waste (MSW) in Maine is demolition and construction waste. Using existing buildings instead of building new can help.

Just composting food waste would also help reduce the quantity of MSW and also save money, since dumping it in landfill or incinerating is priced by the ton and food waste is heavy.