Let's get creative with our office-to-residential conversions

They might be cheaper, faster, and a lot more fun if we throw out the rules.

There’s been a lot of talk about converting our empty office buildings into much-needed housing. I have some experience with this from my days as a real estate developer, having converted George Brown College in Toronto’s Kensington Market into condos. I can confirm that it can be expensive and that the units tend to be deep because of the usual size of the floor plates. Steven Paynter of Gensler tells the CBC that only 25 percent of office buildings are suitable for efficient conversions. Raymond Wong of Altus says, "If you go through all those variables with space layout, the building itself and the anticipated cost, it might be easier to demolish it and start from scratch." The Brookings Institution says, “Office conversion is a very pricey way to add just a fraction of the housing we need.”

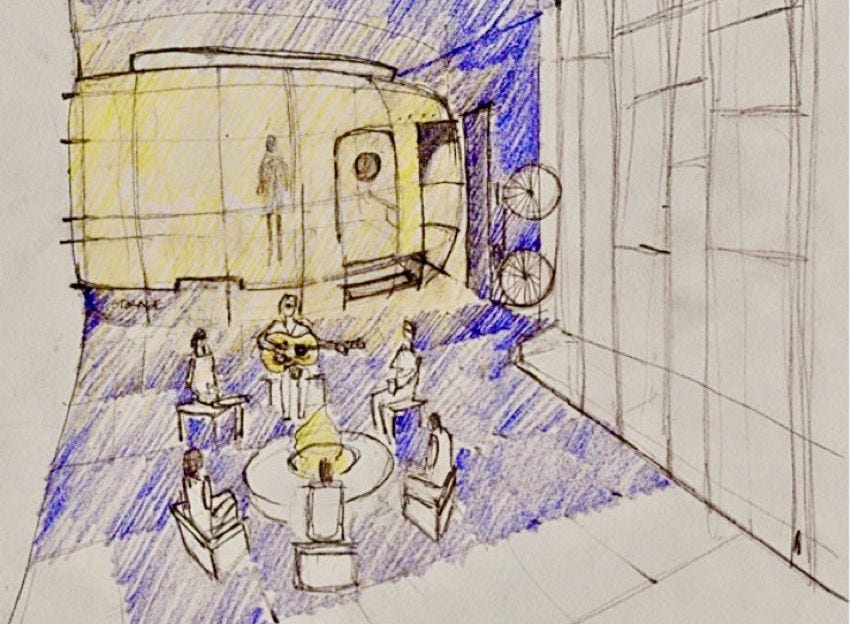

But I can’t help thinking that there might be unconventional opportunities here. We have young people who cannot afford conventional condos in the city; we have co-housing groups that cannot afford land; we have older people who are looking at communal living. And unfortunately, we have a lot of people camping in the streets and parks. Why not take a leaf out of the Hüttenpalast Hotel in Berlin and just clean out the floor, and turn it into a camp ground or trailer park in the sky? Leave all the washrooms in the core, add showers and kitchens there where the plumbing already is, and share them.

The tiny house movement is big, but the problem people have is where to put them. Why not open up office floors for tiny houses? Why not treat the floor plate of an office building as a plot of land in the sky?

This is not a new idea; I first saw it when I was a young architect, when Toronto architect Paul Reuber converted a floor of an industrial building on John St. In Toronto (now Umbra, after a wonderful renovation by Kohn Schnier) Paul designed the bedrooms and other spaces as modules and tells me in an email:

The residential space was on the 3rd floor of a smallish 3-story industrial building with large windows on 2 sides. After completing the Cow Cafe on the second floor, my client’s contractor decided to lease the 3rd floor for his residence and office. A full bath was installed in one corner of the space. The space was actually inspired by the style and configuration of the second floor Cafe as well as my own loft I had renovated above a store on Spadina Avenue.

Essentially, there were 3 modules:

1. Storage modules: as windows were too high for the 3 Chettle kids to look out of, 9 moveable storage units topped with carpeted lids, 1m x 1m x .5 m high were constructed to form an elevated living area. (A similar technique had been employed at one end of the cafe). “Bakers” shelving also used in the cafe and a stair module was built to provide platform balustrades and access.

2. Parents’ module: actually consisted of two modules. A larger module had of an elevated mattress platform suspended over an enclosed walk-in closet, with a desk and bookshelves open at one end. A smaller stair module provided access (steps contained pull-out drawers) to the bed, additional enclosed storage and a bedside nightstand.

2. Kid’s module: 3 modules consisted of a bed platform suspended above a desk, shelves and closet, and privacy panels on two sides of the mattress platform. A door unit could be added for privacy depending on the configuration.

All modules were equipped with wheels for easy movement.

The same concept could work on a co-housing or co-living basis.

Filipe Magalhaes and Anna Luisa Soares proposed a model where IKEA trailers were parked on slabs that could be old office buildings. They tell Designboom that it is “ a political move that seeks the densification of the city through low-cost construction targeting a young and unattached client. on a conceptual level the project attempts to provide an idea that fights the desertification of an unstable economic conjecture, where low cost appears as an affordable solution.”

Years ago, when I helped Treehugger founder Graham Hill on his LifeEdited competition to design a tiny apartment, I loved this entry which constructed an Airstream trailer at one end, and left everything else open for what felt like camping in the apartment. Because until very recently, that is how people lived; Witold Rybczynski explains in his book "Home" that in the Middle Ages, "people didn’t live in homes so much as camp in them."

In "Mechanization Takes Command," Siegfried Giedion writes these were times of “profound insecurity, both social and economic, constraining merchants and feudal lords to take their possessions with them whenever they could, for no one knew what havoc might be loosed once the gates were closed behind him. The deeply rooted in the French word for furniture, meuble, is the idea of the movable, the transportable.“

Many people are living with profound insecurity today. We see many of them camping in the streets and in parks, and others in substandard housing. Perhaps we should rethink some of these office conversions and treat the space as celestial real estate.

That’s what cartoonist A.B. Walker called it in a 1908 edition of Life Magazine, although he was thinking of a more upscale market. But the basic principle still applies.

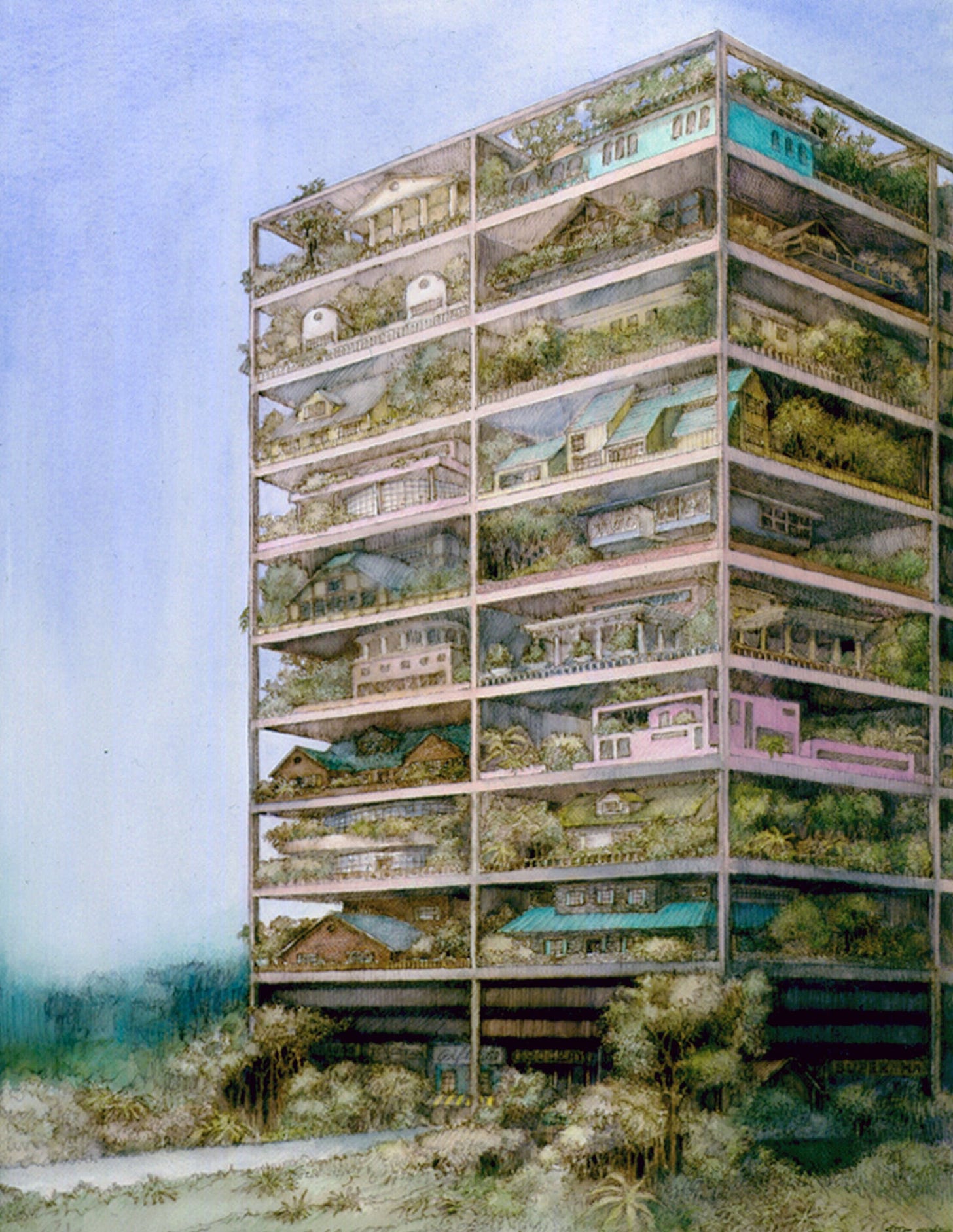

James Wines of SITE had much the same idea in 1981: “a multi-storey matrix that can accommodate a vertical community of private houses, clustered into village-like communities on each floor.”

Plug-in Housing

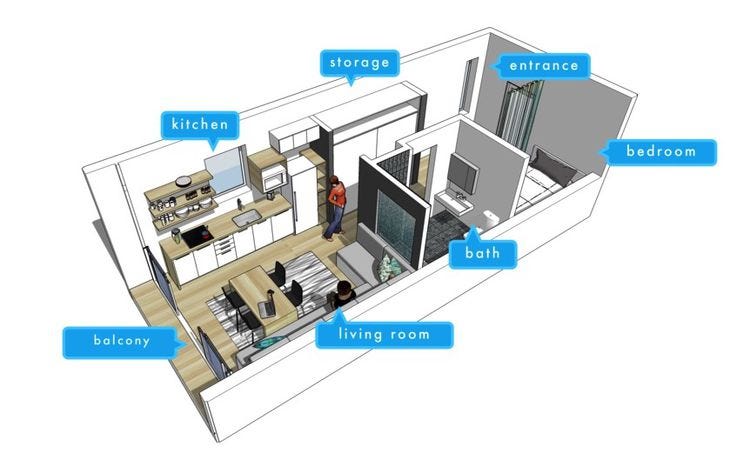

Another option might be to learn from Le Corbusier and plug in prefabricated units. Addison Godine of Live light tried this a few years ago, developing a 385 square foot unit that looks comfortable. The average floor-to-floor height in office buildings is close to 14 feet, which leaves lots of room to design a unit that can slide right in.

Godine planned to build racks where the units, called uhüs, got plugged in, but it could work just as well plugging into existing structures. I loved the business model, which could radically reduce the price of housing. Godine told me at the time:

“The most disruptive idea we have going is that urban housing can be more of a direct-to-consumer business. Our vision is that we or another entity buys the land and develops the exo-structure, but then leaves it at that. What results is a platform for a competitive marketplace of uhüs to develop on: essentially standardized land parcels. The consumer is then empowered to choose their desired uhü, just as consumers today are empowered to choose their desired automobile. By doing this, we greatly reduce the financial investment required of the developer, and put most of the investment burden in the hands of the consumer.”

This is essentially a trailer park model, where the developer owns the land and leases it to the owner of the home. In our modern vertical version, the developer would gut the office building and provide a plug for power, a hose and a drain, much like a trailer park hookup, while the purchaser would bring their unit and plug it in.

Vertical trailer parks make sense just the way condos do; You can accommodate a lot more people and reduce the cost of ownership. Elmer Frey, who invented the mobile home, proposed them way back in 1966. Building an entire structure may have been too expensive, but if you have an existing building, it might work.

These may all seem like silly ideas, like Catherina Scholten’s stage set that so many people thought was real that back in the early days of social media, this image was "racing through the blogosphere faster than headlice through a kindergarten."

But perhaps we need some silly ideas, instead of the conventional ones, if we are going to solve the twin problems of empty office buildings and affordable housing. They seem made for each other.

One of the stranger rules I've read regarding office-to-residential conversions is that windows are required in bedrooms but not living rooms, even if the windows are not meant to be an emergency exit (e.g. a fixed window on the 20th floor). That seems backwards--bedrooms are a place where having no external lighting is okay (to promote sleep regardless of sunlight) but you definitely want some external lighting in the living room!

Wonderful article!