Jargon Watch: Circular-ish vs Circular

Nobody is doing anything even close to true circularity. As Raz Godelnik notes, it's just another form of "sustainability-as-usual."

I have never been fond of “circularity” and “the circular economy,” thinking it little more than a fancy new term for recycling. I have previously written that There's only one way to make the circular economy work: use less stuff, because one will always need inputs of new materials and lots of energy in an expanding economy.

Now Raz Godelnik, an Associate Professor of Strategic Design and Management at Parsons School of Design — The New School, introduces a new term to describe what is really happening now; he calls it Circular-ish. Writing in Medium:

“Circular-ish is an innovation with circularity aspirations that nevertheless fails to entail most, if not all, of the three circularity principles: waste elimination, material and product circulation, and regeneration. It focuses mostly on changes at the materials level or offers incremental business model modifications that do not challenge the core ways in which companies creates and deliver value. In all, it does not reflect a system transformation, but rather a system tweak.”

Being circular-ish looks good but doesn’t represent a meaningful change; Godelnick calls it “another form of sustainability-as-usual, where companies aim to create some positive environmental impact — but in ways and at a pace that do not threaten their core business and the market’s performance expectations.”

Read Godelnik’s full article: Why we are trapped in the era of circular-ish — and how to break free

I like this term circular-ish, and might have used it in my book, The Story of Upfront Carbon, where I did a chapter on words ending in Y, including circularity. Here’s an excerpt:

My dad’s first job was in the circular economy. He married into a family that had what they called an “auto parts” business but could be more accurately described as the city’s biggest scrapyard. If they got a call that a car was ready to be scrapped, he would dash out as fast as he could to get the battery; it was full of lead and the most valuable, portable part of the car. The tow truck would come by later to get the rest.

Labour was relatively cheap relative to the cost of the parts, so it paid to disassemble the vehicle and sell the parts. It was the same with clothing and rags; the rag picker would visit your house and pick them up, and what couldn’t be fixed and resold was turned into fine paper. High-quality draughting paper still is.

Everything used to be circular. In Japan and China, poop would be put in terra cotta jars and left out for pickup for use as fertilizer. It had value; rich people got paid more because they ate better food and produced better poop.

Even our pee was circular. In Ancient Rome, it was used in laundries and to whiten teeth. Later, it had even greater value; the urea in urine breaks down into ammonia, which reacts with oxygen in the air to make nitrates. Mix that old pee with ash, and you get potassium nitrate, or saltpetre, a key ingredient of gunpowder.

Our milk, our Coke, and our beer were circular. They all came in glass bottles that were returned, washed and refilled. There were no litter bins because there was no litter; kids would pick up bottles and take wagons full of them to the store for the deposit. You drank your coffee from a cup at a diner and left it there to be washed and reused.

Then came what I have called the “convenience industrial complex” based on the car, which became a kind of mobile dining room, and the development of plastics, made from fossil fuels, which were much cheaper than the natural materials they replaced, so cheap that they were disposable. We got the shipping container and globalism, which drove down the costs of production so much that it no longer made much sense to fix things; as Emrys Westacott wrote in “the Wisdom of Frugality:”

“There was a time when it almost always made economic sense to repair an item rather than replace it, so people would darn socks, patch sheets, and take their defective video recorder in for repair. But when half a dozen socks cost what a minimum-wage worker can earn in less than an hour, and when the cost of repairing a machine may easily be more than the price of a new one, some of the old ways can seem outdated.”

So we now live in a world where we drive cars powered by fossil fuels to buy food wrapped in single-use plastics, then to the mall to buy polyester socks that are too cheap to repair and fast-fashion clothing that for many people is too cheap even to wash, all shipped over from Asia in ships powered by dirty residual fossil fuels that are alone responsible for 3% of global emissions.

In 1925 Calvin Coolidge said, “The business of America is business,” but today, the business of America is turning fossil fuels into stuff and designing everything so that we need more stuff all the time, and then ensuring that millions of fossil-fuel powered vehicles have to be driven around by shoppers and companies promising two-hour delivery. It is as if the entire system was designed to maximize the consumption of fossil fuels. To paraphrase Robert Ayres: “The economic system is essentially a system for extracting, processing and transforming fossil fuels into energy embodied in products and services.” And in the process, most of that embodied energy turns into upfront and operating carbon emissions.

Enter the new Circular Economy, pitched by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation as “a systems solution framework that tackles global challenges like climate change, biodiversity loss, waste, and pollution.” They note, rightly, that it all starts with design.

By shifting our mindset, we can treat waste as a design flaw. In a circular economy, a specification for any design is that the materials re-enter the economy at the end of their use. By doing this, we take the linear take-make-waste system and make it circular. Many products could be circulated by being maintained, shared, reused, repaired, refurbished, remanufactured, and, as a last resort, recycled. Food and other biological materials that are safe to return to nature can regenerate the land, fuelling the production of new food and materials. With a focus on design, we can eliminate the concept of waste.

None of this is new (our grandparents did it) but it has become the new buzzword; everything is going circular. The plastics industry in particular sees it as its saviour; now that everyone knows that recycling is broken, they have hijacked the concept of the circular economy with what they call “chemical recycling” where they break plastics down to their basic chemical constituents and make new plastics that are indistinguishable from the originals. A report, “Accelerating circular supply chains for plastic” from Closed Loop Partners, claims,

“There are at least 60 technology providers developing innovative solutions to purify, decompose, or convert waste plastics into renewed raw materials. With these available technologies, there is a clear opportunity to build new infrastructure to transform markets. These solutions can also help to decrease the world’s reliance on fossil fuel extraction, lower landfill disposal costs for municipalities, and reduce marine pollution.”

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s approach is more sophisticated, calling for the reduction in the use of single-use plastics and demanding that “No plastic should end up in the environment. Landfill, incineration, and waste-to-energy are not part of the circular economy target state” and “Businesses producing and/or selling packaging have a responsibility beyond the design and use of their packaging, which includes contributing towards it being collected and reused, recycled, or composted in practice.” But all this collecting and reuse by somebody else and recycling takes energy and releases carbon. The 60 technologies pitched by the circular plastic people take vast amounts of energy to break plastics down to their molecular components; it’s probably more than just making the virgin stuff.

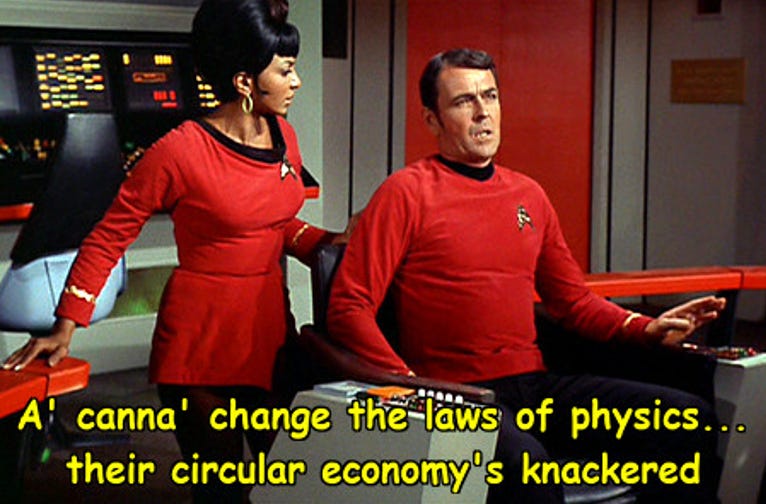

In most circular economies, there is a form of entropy happening with the laws of thermodynamics in play. The aluminum people will keep saying that it can be recycled infinitely, but impurities in the aluminum mean that it can’t be used for everything, and it still takes energy to do it. Paper deteriorates as the fibres get shorter. PET gets contaminated, so it cannot be turned back into water bottles. The more complicated the chemical recycling process gets, the more fuel it needs and the more carbon it releases.

You can’t fight the laws of thermodynamics; it took energy to put the original product together, and because of the tendency to increasing entropy and disorder, it takes more energy to make it circular. As noted by Jouni Korhonen,

“Because of entropy, like all material and energy using processes, circular economy promoted recycling, reuse, remanufacturing and refurbishment processes too will ultimately lead to unsustainable levels of resource depletion, pollution and waste generation if the growth of the physical scale of the total economic system is not checked.”

The circular economy cannot exist in a growing economy; it just takes too much to run. It wants to stay linear because that is how the universe works; things break down to lower energy, disorder, and waste. The only thing we can do is slow down the process; as Korhonen notes, “the second law of thermodynamics means that every circular economy-type process or project should be carefully analyzed for its (global) net environmental sustainability contribution. A cyclic flow does not secure a sustainable outcome.” We must make choices, use less, design for repairability and reuse, and stop pretending that recycling is circular; the recycling industry has just co-opted the term.

yes! when we talk about circularity we must first be talking about "doing nothing" and "durability". Whole-system reuse and the "why" behind things NOT getting reused. Otherwise "circularity" is simply another form of "recycling potential" which is greenwashing. That said, i think the original intention of the term is sound, it has just, like all things, been through the capitalist spin-cycle.