It's Launch Day for the Story of Upfront Carbon!

Lisa Richmond of the AIA Committee on the Environment reviews my book.

Today is the official launch of my book The Story of Upfront Carbon. I am very nervous. Will people like it? Will it find an audience? Why am I suffering from writer’s anxiety, which is apparently a thing? I have been fortunate in that the first review of my book is positive! It was published on the AIA blogs and written by Lisa Richmond. Here it is, reprinted with permission:

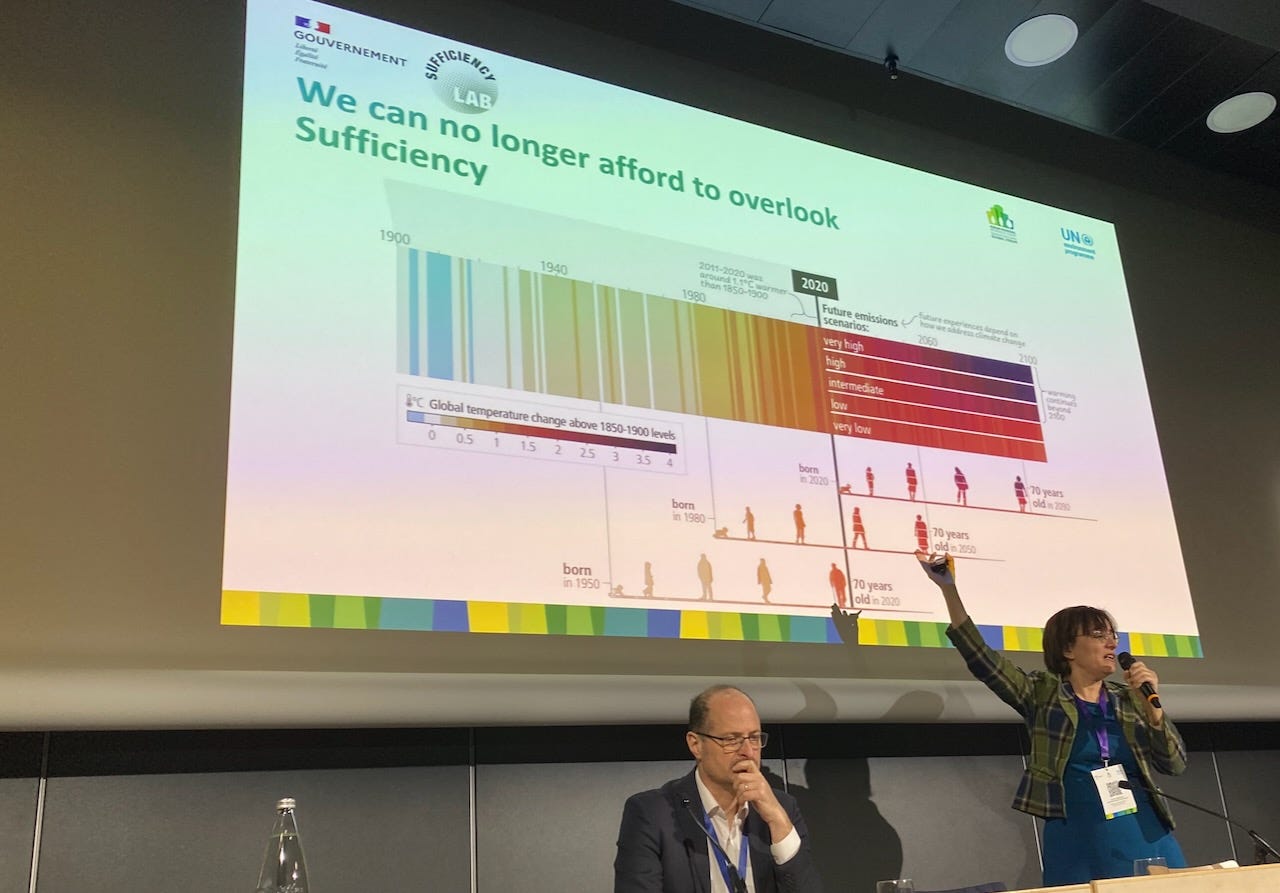

Lisa Richmond is a Senior Fellow with Architecture 2030 and a consultant and strategic advisor with Climate Strategy Works, helping organizations and firms center climate action in strategy and operations. She recently helped convene a session on Sufficiency, featuring Lloyd Alter as a speaker, at the Buildings and Climate Global Forum in Paris.

As a fan of Lloyd Alter's writing, I knew his new book would be provocative. Like Living the 1.5 Degree Lifestyle and his excellent Substack, I expected The Story of Upfront Carbon to help me see the world in new ways. What I didn’t expect: it would be such a delight to read. The book is honest and practical, making complicated subjects accessible using simple, everyday examples. It’s not written for architects, but nonetheless offers rich systems-level thinking about decarbonizing the built environment. This is a sophisticated embodied carbon primer my mother could understand, even enjoy.

Sufficiency: the art of just enough.

Like much of his previous work, Alter’s new book probes the most important, yet least understood, pillar of climate action: Sufficiency, demand management, or the practice of using just enough. In a world of supply-side solutions (new EVs, new solar panels, new heat pumps), sufficiency thinking asks, how can we make do with less?

In its most recent IPCC report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates that demand-side measures could reduce global GHG emissions by 40–70%. And thanks to the time value of carbon, those savings crucially come in the immediate future, not over the life of a building or infrastructure project. Sufficiency strategies aim to “avoid the demand for energy, materials, land, water, and other natural resources, while delivering well-being for all within planetary boundaries," says IPCC lead author Yamina Saheb. “For me,” she shared at the Buildings and Climate Global Forum, “efficiency on its own is business as usual. We simply cannot afford it.”

Build less stuff.

Practitioners in the built environment understand the critical importance of embodied carbon. The manufacture of common building materials is responsible for 11 percent of global carbon emissions. A raft of tools and strategies, from Architecture 2030’s Carbon Smart Materials Palette to Buildings Transparency’s EC3 calculator to the increasing popularity of mass timber, have entered the industry to support better materials choices.

But what if we started by asking the simple question, “should we build?” "You can minimize the amount of material that you use (put simply: use less stuff), or you can minimize the amount of carbon released when producing those materials," Alter writes. "How can we design our lives and our world to use less?"

And using less is critical if we want to achieve ambitious Paris goals. The most recent Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction is clear: any recent gains in operating efficiency have been more than offset by global growth in floor area. “The answer,” says Alter, “is we have to simply build less stuff. Build nothing; Build less; Build clever; Reuse.”

How do we make do with less? Alter offers concrete examples. Design for flexibility, optimize use, prioritize multifamily dwellings. Progressively tax per-capita floor area. Design for deconstruction and disassembly so that materials can be recovered. Repurpose existing buildings. "Refurbishing, renovating, and repurposing buildings may well be the major construction challenge of the next few years," he argues.

Alter doesn’t shy away from strategies that may be a bitter pill for professionals who have spent their career designing things. He scorns starchitect "monuments to upfront carbon.” "Buildings want to be boxy," he asserts. “Less Bjarke, more boring,” he commands. Putting sufficiency first requires seeing design through a different lens.

A matter of justice.

Reining in consumption is not only an existential necessity, it is a moral imperative. Our carbon budget is rapidly shrinking, and every extra ton of emissions we put in the atmosphere is a ton that someone else can’t use. "If one accepts that there are about five hundred gigatonnes of carbon budget left if we are to stay under 1.5°C," Alter asks, "a big question is: who gets it?" The 2023 UN Emissions Gap Report finds that to eliminate carbon inequality, the richest 10 percent would need to reduce emissions by more than 90 percent.

What would carbon budget rationing look like in the built environment? We have always measured progress against where we used to be; the 2030 Challenge for Embodied Carbon, for example, calls for “embodied emissions to immediately meet a maximum global warming potential of 40% below the industry average today." But Alter uses a different standard - where we OUGHT to be to stay within the carbon budget - and digs into the sticky business of how those remaining emissions allowances are allocated.

Degrowth: the inconvenient truth.

This leads us directly to the third rail of international climate dialogue: Degrowth. There is no avoiding the truth, says Alter: "A world where we must use less stuff to reduce carbon emissions … means that economic degrowth isn't a choice, it's an inevitable result."

The question for those who make their living designing and constructing buildings is: What are the business models that will help us thrive in a sufficiency economy? For this, Alter has no real answer. The book ends with a "cheat sheet" focusing primarily on individual behavior, not systems change. As much as individual architects and firms might want to, it will be incredibly hard to fly the flag of sufficiency in a world still built for overconsumption. Useful thought experiments come to mind: British economist Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Design for Business or the Next Economy project, for example. And perhaps, Lloyd Alter, a third book?

The Story of Upfront Carbon is available from New Society Publishers in Canada and the United States. It’s also available in Kindle edition from that big online site.

Like the other folks here, congrats on the successful end to an arduous project to take on: what to put in, what to leave out, shove something else in, and slice it down again. And having the discipline to sit down and "get'r done". Even though, I disagree with some main premises (if I can extrapolate from your writings here and at TH), one HAS to admire the effort and long hours.

Now, that said (and yes, you knew this was coming), I read a few things in the review that require comment. The most obvious one is "...and digs into the sticky business of how those remaining emissions allowances are allocated."

Have you been holding out on us, Lloyd? As in WHO gets to do the allocation, what is the decision system behind that, what are your means of doing that allocation, and how are you going to deal with the pushback against it (e.g., the Dutch Government just fell because of "doing with less" as well as "we're putting you out of business because emissions"?

Or will that last bit be the focus, as VB said, of your next book.

I have a few other questions but I'm juggling a few too many balls right now and I, individually, need to determine priorities and allocations. Later, sir!

Delicious irony in LR's favourable review: "How do we make do with less? Alter offers concrete examples."