Is nostalgia stealing our kids' future?

From the archives: We keep voting for people who promise to make things like they were, forgetting that things could be awful.

My recent post, The coming crises caused by aging baby boomers like me, got a generally positive response! I wrote a lot about this subject for the Mother Nature Network, which was absorbed into Treehugger and where this stuff didn’t really fit. Fortunately I was able to archive most of it and will republish my favourites here. This was written in 2018, just after the election of Doug Ford in Ontario, Canada, and two years into the Trump administration. More positive and upbeat posts to follow.

Where I live, in Toronto, Canada, a "right wing populist" has just been elected the premier of the second largest government in the country with an economy as big as Switzerland's. Two of the key items in his platform are to roll back the sex education curriculum to 1998, and to bring back beer for a buck. He's also rolling back gas prices, perhaps nostalgic for the time when you drove down Main Street drinking beer and learned about sex in the back seat.

He's obviously not alone; south of the Canadian border, the president of the United States has been trafficking in nostalgia. On the economic front, he's trying to bring back coal and steel, but as Brad Plumer notes in the New York Times,

But while the approach has helped Mr. Trump remain popular with many working-class white voters, it has done little to help those populations prepare for changes that could further decimate their professions.

Socially, Trump appears to be feeding a nostalgia for a simpler time when everybody knew their place. A lot of people want this and voted for him to Make America Great Again, to make things like they were. For some, these were good times, especially if you had a unionized job at the factory. But for others, things were not so great.

This is a global phenomenon; Philip Stephens writes in the paywalled Financial Times that "America's Donald Trump, British Brexiters, Europe's new nationalists — they all inhabit a rose-tinted past."

Nostalgia's force lies in a human instinct to screen out the bad while recalling the good. The tendency, I have learnt, becomes more pronounced with advancing years. Hard times become fond moments of shared endeavour and community. With the passage of years, the terrible threat of thermonuclear war can seem like the benign guardian of a stable and peaceful international system. Materially deprived we may have been, but there was something spiritually special about being spared the instant gratification of the digital age.

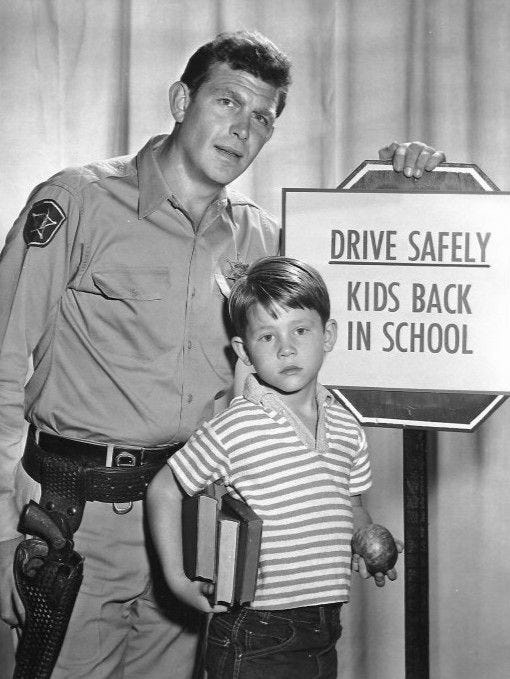

Stephens notes that East Germans are nostalgic for the security and steady employment of the communist days; Swedes, for the closed, homogenous Sweden of the 1960s. But the thing is, in the West, we seem to be nostalgic for the times of greatest change. The space race, transistors, the pill, the incredible changes that traumatized our parent's generation and energized ours. We watched Andy Griffiths on TV but would die before we'd live in Mayberry. Now, we imagine it's reality. Stephens writes:

The deep irony about the now mythologised postwar decades, however, is that these were times when citizens looked unambiguously to the future. Technological advance was seen as progress, liberalism promised emancipation. The age of Sputnik, colour television and The Beatles was all about shedding the past. Its confidence flowed from the embrace of modernity. The emotions were progressive, welcoming of new technology and newcomers alike. And now?…. People who have lost faith in the future are seeking solace in old, imagined, certainties.

There is, of course, a solution coming, courtesy of the inevitability of demographics. There are already more millennials than there are baby boomers; they just vote at half the rate that their parents do. In not too long, they will outnumber the boomers and their elderly parents at the voting booth, too. As Stephens concludes, the only way anyone will get elected then is if they "explain how to ensure our children are better off than their parents." That will be tough, considering what we're leaving them after we burn all the furniture.

Tiny but significant copy edit: FORMER president Trump. We did actually manage to vote him out—even if he didn’t get the message.

Lloyd, please refer to your blog title and stick to it - this re-publication reignites flammable political differences in a foreign country.