In which I sheepishly learn about the merits of wool insulation

An example of how hard it is to make informed decisions about building materials- it's complicated!

LinkedIn makes me crazy, but I still look at it, and came across a post by Harry Urquart-Hay, a New Zealand wool entrepreneur, extolling the virtues of wool. New Zealand generates a lot of wool, and some is used as building insulation. As a fan of natural materials, I liked the idea and often wrote about it. But like everything in the built environment, it’s complicated.

Wool obviously comes from sheep, and sheep are a problem because they are ruminants and their digestive systems produce a lot of methane. When I visited New Zealand last fall to speak at a Passivhaus conference, I took the Northern Explorer train from Auckland to Wellington, listening to a history of New Zealand and looking at the scenery. I wrote in my post about the trip:

“In many ways, I found it profoundly depressing; the forests were cleared away with saws and fire, so that now you have mainly rolling hills covered with cows and sheep as far as you can see. The rainforest that might have been a big part of the lungs of the planet was cleared to produce meat and dairy (25 million sheep and 6 million cows) and methane; it’s basically 150 years of climate disaster.”

Then there is the question of wool’s carbon footprint; According to the Material Carbon Emissions Guide prepared by Builders for Climate Action, wool came in at 296 kg of CO2 per square meter, squished between open-cell spray foam and blown-in fibreglass, far higher than any other natural material. That’s because Life Cycle Assessments apply an allocation of the greenhouse gas emissions from the sheep to the wool as well as the meat.

Between deforestation and methane, I became less enamoured of wool.

But then I learned that the coarse wool has little value; in Scotland, it is sometimes burned or buried because prices are so low that it is not worth the trouble to sell. So, based on economic allocation, all of the emissions should be attributed to the meat, and wool insulation would drop down the ladder to sit with natural materials that store carbon. Much depends on who did the LCA and where they draw the boundaries, and how they treat methane from animals as a greenhouse gas, an ongoing debate.

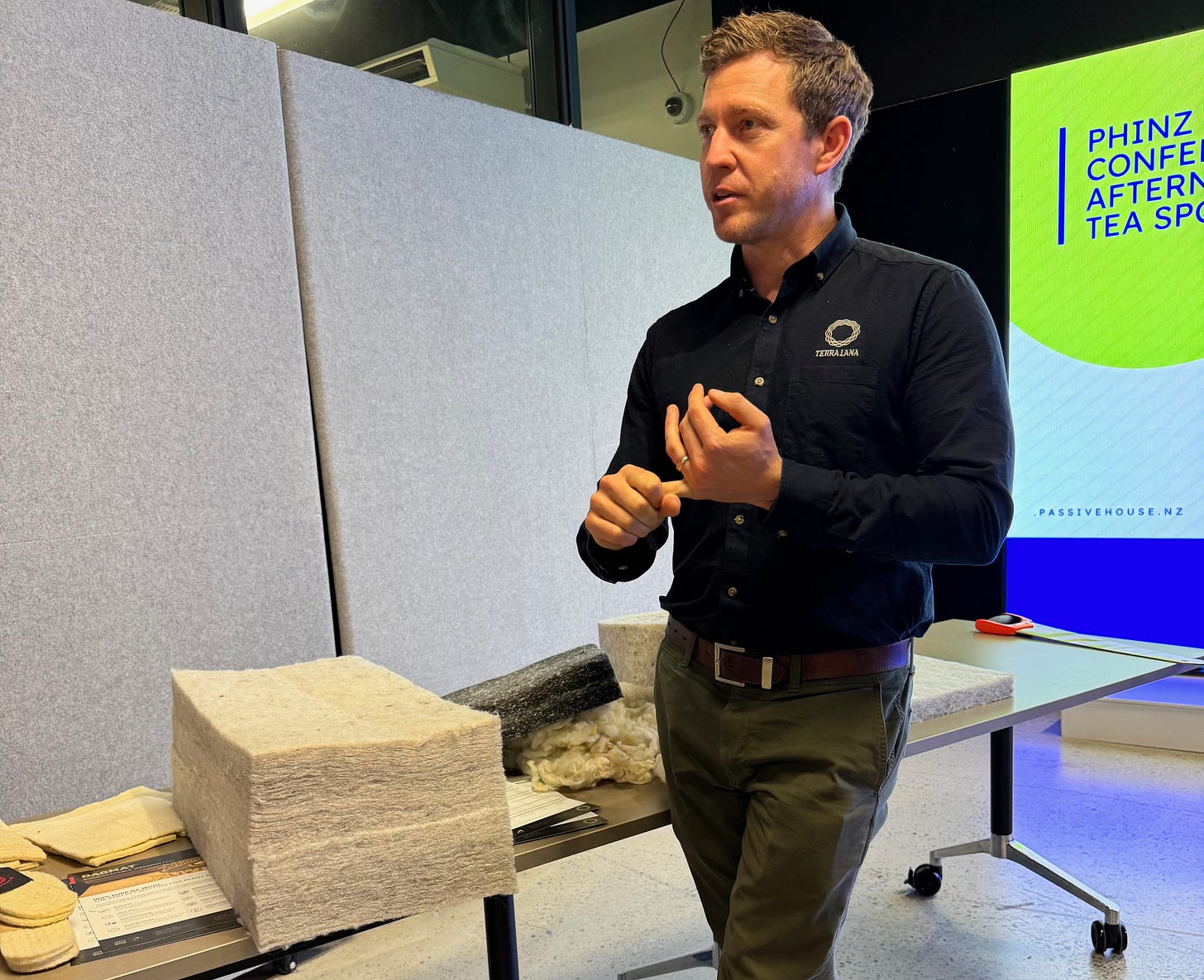

When I was at the Passivhaus conference, I was very impressed with Brad Stuart of Terra Lana, which produces wool insulation in Christchurch. They tell a great sustainability story:

“We blend pre-consumer industry waste wool with local virgin waste wool sourced from a collective of family-owned farms located less than an hour’s drive from our Christchurch factory. This proximity offers multiple benefits: reduced transportation emissions, enhanced fibre quality control and traceability, and a positive economic impact on the local farming community. By partnering with nearby suppliers, Terra Lana ensures sustainable sourcing practices while supporting regional agriculture.”

The problem is that the wool is melt-bonded with PET from recycled bottles to maintain its loft; it can be as high as 40% plastic, although most appears to be about 25%. It’s wonderful that they use recycled PET, but some argue that using PET from bottles for uses other than bottles means that the bottle makers need more virgin PET, so it doesn’t significantly reduce primary demand. I asked an architect at the conference what he thought about wool insulation, and he said he didn’t touch the stuff because of the PET.

This is why making decisions about materials is so complicated and challenging. I certainly can’t blame the wool insulation industry for the devastation of the rainforests of New Zealand or the Highland Clearances in Scotland. If the wool is a waste byproduct of the meat business without much value, then it’s hard to attribute much of the methane emissions from the sheep to the insulation. And while we want the PET bottle industry to be truly circular, it isn’t; most bottle makers want to use virgin PET, so downcycling the plastic to insulation isn’t a terrible idea.

I am going to give the last word to Damien McGill, Passive House Consultant at Healthy Home Cooperation and my host when I was in Christchurch. He completely terrified me, taking me on a drive on some of the scariest, narrowest roads I have ever been on, in his little old Toyota Yaris with tiny shopping cart wheels- I used to drive the same car and wouldn’t even think of taking it where he took me. He responded to the Linkedin post:

Lloyd, I think we needed to find some narrower roads 😉

The reforestation is happening, but primarily as a monoculture of pinus radiata, which isn’t ideal either.

We are where are. Progress in the 1800’s is different to now. In hindsight they did terrible things; introducing rabbits, then mustalids to control them. Possums for fur, etc. etc.

Progress now should be utilising what we have to it’s maximum potential while considering sufficiency.

Coarse wool is a byproduct of the Sunday roast lamb or BBQ lamb chop industry. It costs more to shear the sheep than the wool is worth, so wool is stockpiled in warehouses, when it could be used to insulate Aotearoa’s cold damp draughty homes.

Is it better keeping Kiwi’s warm or🐀 and 🐁 warm?

What’s the point in burning fossil fuels or growing crops to create insulation products, when the material is idly lying around?

(We could also use straw and hemp where grown as a byproduct of the grain industry, too.)

Wool is not perfect, thermally nor in other ways, but it’s a good news story for NZ farmers, who much like the Southern Alps are the spine of our economy.

Thank you, Damien, and please, no narrower roads.

Special offer!

I do not want to put up a paywall on this site, but it provides a meaningful portion of my income. So here’s a limited-time offer: I will send a signed copy of the print edition of “Living the 1.5 Lifestyle” to anyone in the USA or Canada who signs up for a one-year subscription (C$50, cheap at about US$35 ). I am running out of stock, so hurry!

My uncle is a sheep farmer in Ireland. He has hundreds of kilos of sheep's wool, maybe thousands, and the stuff is basically worthless. The sheep are raised for meat (which is a whole other issue) and have to be sheared every year for their own comfort. The wool isn't soft enough for sweaters but used to be sold to a company in England where it was used to make big industrial wool carpets. But prices are so low the sale wouldn't even cover the cost of shearing or transport. Even getting it for free I tried to find a way to get in converted into insulation (it's filthy and takes a lot of water and effort to clean properly) for my own use but I couldn't make it work. If anyone knows of a company that can clean and dry fleece in Ireland please do let me know!

A wonderful example of how complex the process of addressing a hotter planet can be. The world is a messy place that we increasingly attempt to understand in terms of sound bytes and antisocial media posts.

It takes more than first order thinking to understand the complexity of the environment and our impact upon it. Yet we rely on likes and up votes to inform our decisions. "Explain it in 15 seconds or less or I can't be bothered to pay attention to what you are saying." There seldom are simple solutions to complex problems.