Imagine these houses with acrylic stucco and vinyl windows

An economist says there is an "emissions gap" caused by regulations for historic districts. He's not looking at the bigger picture.

I started writing this post after reading an article illustrated with this beautiful photo of a street full of old houses, and after writing about zoning and air leakage, I got to the windows section and found that I had written about the study behind this article, by the same author, back in February in The deluded world of window replacement. I was about to chuck the whole thing, but thought I might as well publish this. It ends rather abruptly when I discover that I am about to repeat myself.

F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote, “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” I do not claim a first-rate intelligence and sometimes wonder how I can function, writing one day about high-performance buildings and the next day about leaky heritage ones, and can only suggest that they are not really opposed ideas.

Take, for example, this article titled The environmental burden of aesthetic norms by Thiemo Fetzer of the Centre for Competitive Advantage in the Global Economy and a professor of economics at the University of Warwick. He writes about how regulators protecting heritage buildings and districts are responsible for massive carbon emissions. He illustrates his post with a bucolic scene of a narrow street with small homes and not a car in sight.

“This column explores the barriers to climate action in England implied by conservation areas, where simple retrofitting measures such as double glazing or the installation of solar photovoltaic panels require approval, a potentially lengthy and often expensive process. The findings suggest the desire to maintain an “appealing character” in these areas comes at a cost of 3 to 4 million tonnes of avoidable CO2 emissions per year.”

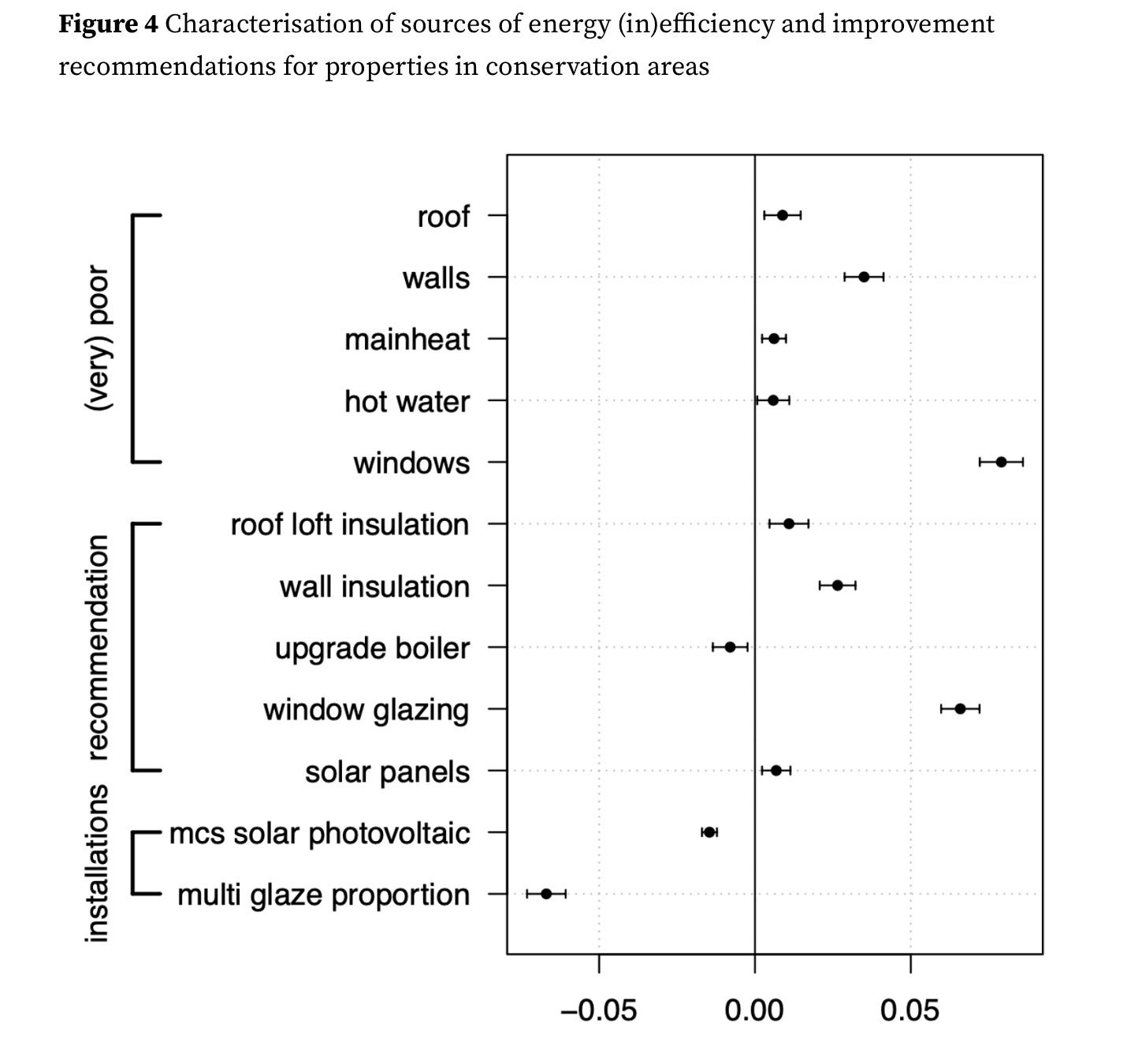

Fetzer studied buildings within heritage districts to those nearby and found an “emissions gap,” a significant difference in energy consumption between buildings inside conservation districts and those outside. “The results showed that the drivers of this widening gap are window glazing and exterior wall insulation – the factors that most strongly affect the exterior appearance of a property and, as such, are the most strictly controlled within a conservation area.”

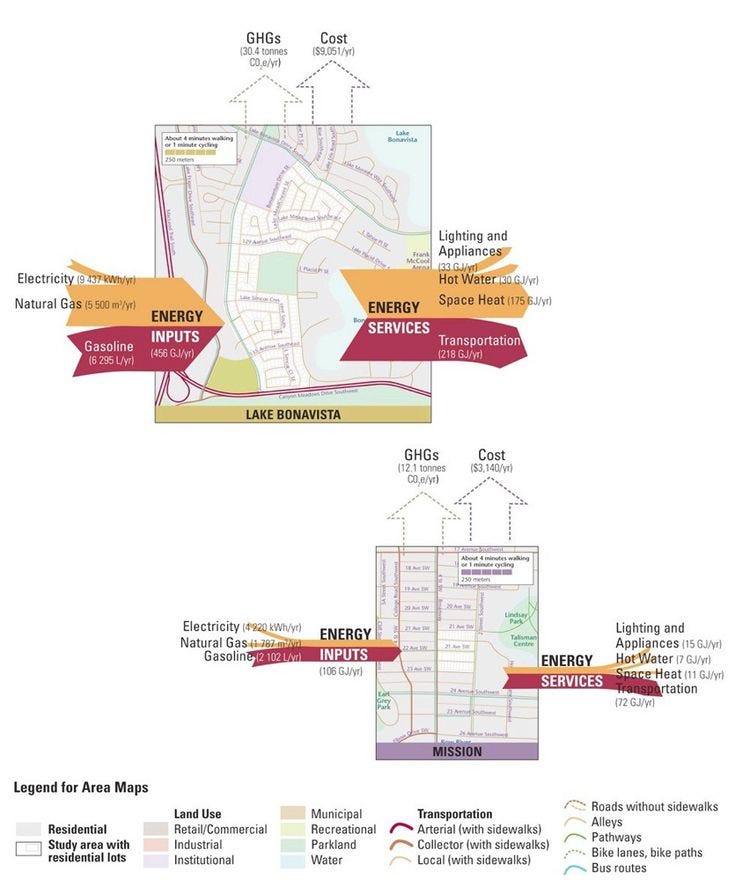

There are a few problems with Fetzer’s thesis. the first is that he is looking at the emissions from houses in isolation. Study after study have shown that emissions per capita are proportional to density, and our heritage districts are often significantly denser than our newer ones. other studies, like Archetypes study by Natural Resources Canada showed that people living in leaky old small homes and apartments, like in the Mission District of Calgary, have emissions that are a fraction of those who live in newer suburbs. Look at the difference in the energy inputs in the illustration above. This was consistent in all 12 cities that the study examined. This is why I have written that the great hypocrisy is that the single biggest factor in the carbon footprint of our cities isn't the amount of insulation in our walls, it's the zoning.

The people who live in those little houses in the photo live in a community designed before the automobile. They live in the original 15-minute city where they can walk to get most of their daily needs. And they likely have significantly lower total emissions per capita than those living outside the heritage districts, since in the UK 24% of CO2 emissions come from transportation and 16% come from residential. That’s why when I wrote about the top five ways to reduce carbon emissions in your home for Green Building Advisor, selling the car was on the list.

Then, there is the question of whether Fetzer’s prescription of exterior wall insulation and replacement of window glazing makes sense. Ignore the question of how that photo would look if all those houses were clad in stuccoed styrofoam with vinyl windows, and look at the numbers. The British don’t seem to like blower door tests, and generally have no idea where the heat loss is, but it’s usually not the windows and walls; it’s air leakage, which isn’t even on Fetzer’s radar. (he is not alone) Window replacement is very expensive, and the bang for the buck in terms of energy savings is lower than just about anything else you can do. Harold Orr, who won the Order of Canada for his work on energy saving in houses going back to the Saskatchewan Conservation House in the seventies, said in an interview:

“When you put styrofoam on the outside of a house, you’re not making the house any tighter, all you’re doing is reducing the heat loss through the walls. If you take a look at a pie chart in terms of where the heat goes in a house, you’ll find that roughly 10% of your heat loss goes through the outside walls.” About 30 to 40 % of your total heat loss is due to air leakage, another 10% for the ceiling, 10% for the windows and doors, and about 30% for the basement. “You have to tackle the big hunks,” says Orr, “and the big hunks are air leakage and uninsulated basement.”

It will be different in the UK, where generally they don’t have basements, but the biggest hunk is still going to be leakage. Other studies have also shown that old windows can be made almost as airtight as new ones, and they can be effectively double-glazed with window inserts that do not change the exterior appearance and cost a fraction of what new windows cost.

And here is where I searched for articles that I had written about window replacement and discovered my previous discussion of Fetzer’s work. Read The deluded world of window replacement.

As someone who lives in a leaky and poorly insulated old house, I'll add that doing so modifies one's

behavior. I don't even try to heat my whole house. I tend to heat one room at a time and I also

wear multiple layers. This doesn't work for everyone, but it is a stategy that was pretty much the norm

untill recently.

"Acrylic stucco and vinyl windows" are a false dichotomy--why not imagine these houses with exterior insulation, lime stucco, and wooden simulated double hung, triple glazed tilt/turn windows?

Another issue is that these houses won't just have to deal with the cold in the future--they'll also have to deal with the heat, something that this article ignores, yet another example of cold climate bias that the green building community is struggling to overcome. You can't deal with the heat by airtightness alone--insulation and glazing has to be part of the solution, and internal glazing inserts aren't going to help as much as external ones because 1) they take up space needed by shades and 2) they have a nasty habit of trapping heat between themselves and the original window, causing damage to the latter.