How to build a low-carbon home

An exhibition at the Design Museum tells us to do it with stone, wood and straw.

After being in Paris for the UNEP Buildings and Climate Global Forum, I left in a hurry on Sunday morning to get to London before the closing of the exhibition at the Design Museum, “How to build a low-carbon home.” I was excited by the premise and the people:

“This display explores three ancient materials that are vital for a low-carbon future: wood, stone and straw. Through the work of contemporary architects Material Cultures, Waugh Thistleton and Groupwork, as well as engineers Webb Yates, follow the journey of these materials from fields, forests and quarries to cutting-edge buildings.”

I should have enjoyed the day in Paris; less rain and better exhibitions. But the premise and the people still excite, particularly in the light of the Declaration de Chaillot signed last Friday, which calls for the use of “local, sustainable, bio/geo-sourced, low carbon, energy efficient materials.”

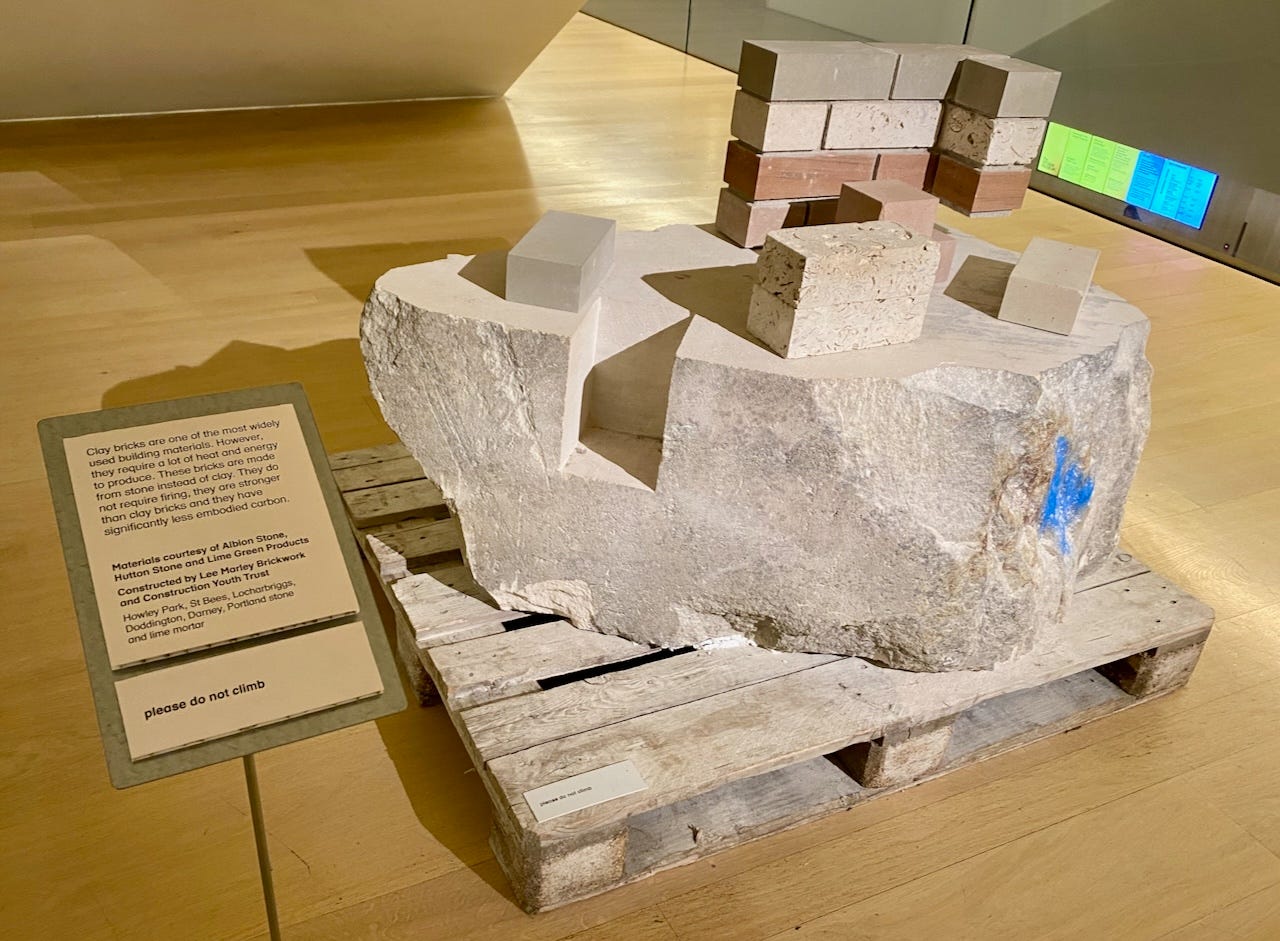

Of the three materials examined in the exhibition, I find stone to be the most fascinating. Steve Webb of Webb Yates makes such a persuasive case for it, telling me earlier for an article in Green Building Advisor that it is “perverse” to grind up and cook limestone into cement.

“Current practice in building is to take high-strength limestone with a strength of, for example, 150N and expend huge amounts of carbon, converting it into much lower-strength concrete (40N/mm2). Not only is it perverse to do this, but the carbon footprint of concrete is 250% higher than stone for a material with only 25% of the strength.”

His proposed house of stone shown in the exhibit seems a bit perverse, with its stone roof truss that could have been so much lighter in wood, but it is certainly provocative.

If you want a masonry wall, (which it appears everyone in the UK does) the use of stone instead of brick makes tremendous sense. In the developed world, firing bricks uses a lot of heat and energy, usually from natural gas, whereas stone units are stronger and have far lower upfront carbon emissions. Will Arnold of the Institution of Structural Engineers wrote on Linkedin this morning that “the world makes more than 1 trillion bricks each year.” In much of the world, brick-making is “a system of modern day slavery.” We don’t need to do this anymore; Webb Yates and Groupwork show us how we can cut stone instead of cooking clay.

Much of the exhibit related to straw is behind plastic and my photos are full of awful reflections, so I can’t show you the images of Flat House, the marvellous hemp and straw building in Cambridgeshire from Material Cultures that I previously covered in Treehugger. The architects write:

“Straw can be used for building in many different ways, by combining it with other natural materials such as clay or bio-waste resins to make walls, bricks, insulation and other modern components. Straw also absorbs carbon dioxide when it grows, making it an environmentally friendly material for contemporary homes.”

I adored this house, with the texture of the hempcrete, the almost Tudor construction of infill between the exposed wood, described by architect Paloma Gormely as "a low-tech approach and bio-based materials can be combined with off-site construction to create a scalable low-impact, beautiful architecture." While I didn’t quite agree with her thoughts about thermal comfort where "the orchestration of natural materials creates a building that regulates humidity, temperature and air quality without the need for ducting or equipment," I thought if this is low-carbon architecture, bring it on.

There was dissapointingly little to see in the wood department from Waugh Thistleton; a model of their wonderful Dalston Lane, and the mockup of their Murray Grove timber tower completed in 2009, the building that started it all, which looked a lot better when I saw it in the Victoria and Albert plywood show back in 2017.

All of this didn’t add up to the original billing and title, “How to build a low-carbon home.”

It would have been wonderful if Paloma Gormely, Steve Webb, and Andrew Waugh sat around a table and designed a home together with stone foundations and columns, a timber frame with hemp and straw infill, and a timber roof, examining and taking advantage of the best properties of each material and giving us a complete model of low-carbon design.

Perhaps I am still in a daze from Paris, but we are in a new, post Declaration de Chaillot world where we have to change what and how we build. The era of burning stuff is over; we don’t need kilns and furnaces. We have seen here how we can build foundations without concrete, we can insulate with natural materials, we can replace steel with wood. This story doesn’t end with the closing of this exhibit; it is just getting started.

I absolutely love the idea of hempcrete. I believe it is non-structural, though, and requires framing if it goes to any height - rather like a half-timbered building. I stayed iin a 450-year-old half-timbered house for a couple of weeks once, courtesy of the wonderful Landmark Trust. It was a very cold December, and the plastering had all shrunk away from the beams, leaving gaps of up to an inch through which the wind whistled, and through which we could see the black night sky. We froze! Is that a known issue with hempcrete?

Definitely a lightbulb moment