How bio-thinking might help us out of our carbon crisis

But first, we have to learn all the different bio buzzwords.

In March, I attended the Architect@Work conference in London, including a “Nature’s Blueprint” session that included architect Jerry Tate. The Tate + Co website states, “The common thread to all our projects is their broad positive impact. To achieve this, we employ a Regenerative Design approach, seeking to increase the natural, social, human, financial and manufactured capital every year, forever.”

Jerry discussed regenerative design in his presentation and showed a slide with the usual images people associate with biomimicry, bones, and leaves, but down at the bottom left, there was an image that excited me: the carbon cycle.

My basic (and incorrect) understanding of biomimicry was that one mimicked biological forms like bones and leaves and that looking at wood and plants made you feel better; where did the carbon cycle fit in?

Given that I teach sustainable design, I am loath to admit to my misunderstanding, but a visit to the Biomimicry Institute website and a link to an article by Allison Bernett quickly set me straight. It turns out that there are a bunch of bio buzzwords, under the general heading of “bioinspired design, but as they say at the Biomimicry Institute, While biomimicry is a type of bioinspired design, not all bioinspired design is biomimicry.

I was conflating biomimicry with biomorphism, where a building might have natural forms and patterns but not actually follow biological principles.

I have also written for years about biophilia, E.O. Wilson’s term for “humanity’s innate response to nature and connection to natural systems.” Biomorphic and biophilic designs make us feel better and improve health but do not necessarily function like nature. Tye Farrow’s work, which I recently showed, is both biomorphic and biophilic in that it follows natural forms and patterns and definitely improves health.

Then there is bioutilization, described by the biomimicry Institute as “the use of biological material or living organisms in a design or technology. For example, using trees as a material (wood) for furniture or a living wall of plants to help clean the air in an office building is bioutilization.”

But true biomimicry “translates nature’s strategies into design…Circularity, sustainability, regenerative design—it means that the things we humans make become a force for restoring air, water, and soil instead of degrading it.”

Now, I was getting back to my comfort zone; I have even tried to get the course I teach renamed from “sustainable design” to “regenerative design” because it isn’t good enough anymore to just be sustainable, to keep things from getting worse; we have to make them better.

All of this brings us back to Jerry Tate and his Serpentine House, which he graciously shared with me. It is a wonderful example of regenerative design, which in many ways is true biomimicry, attempting to work like that carbon cycle.

It was approved under legislation that lets you build on green belts or restricted land-

“The scheme gained planning consent under the ‘Country House Clause’ called Paragraph 80 of the NPPF. This allows planning permission to be granted in an open countryside setting so long as the proposal is truly innovative, sustainable, and deeply related to the local environment. We worked closely with several consultants and East Suffolk Council, including extended pre-application meetings and presentations to the Design Review Panel, to develop the design and demonstrate that the scheme will be both beautiful in its setting and revolutionary in its approach to regenerative design.”

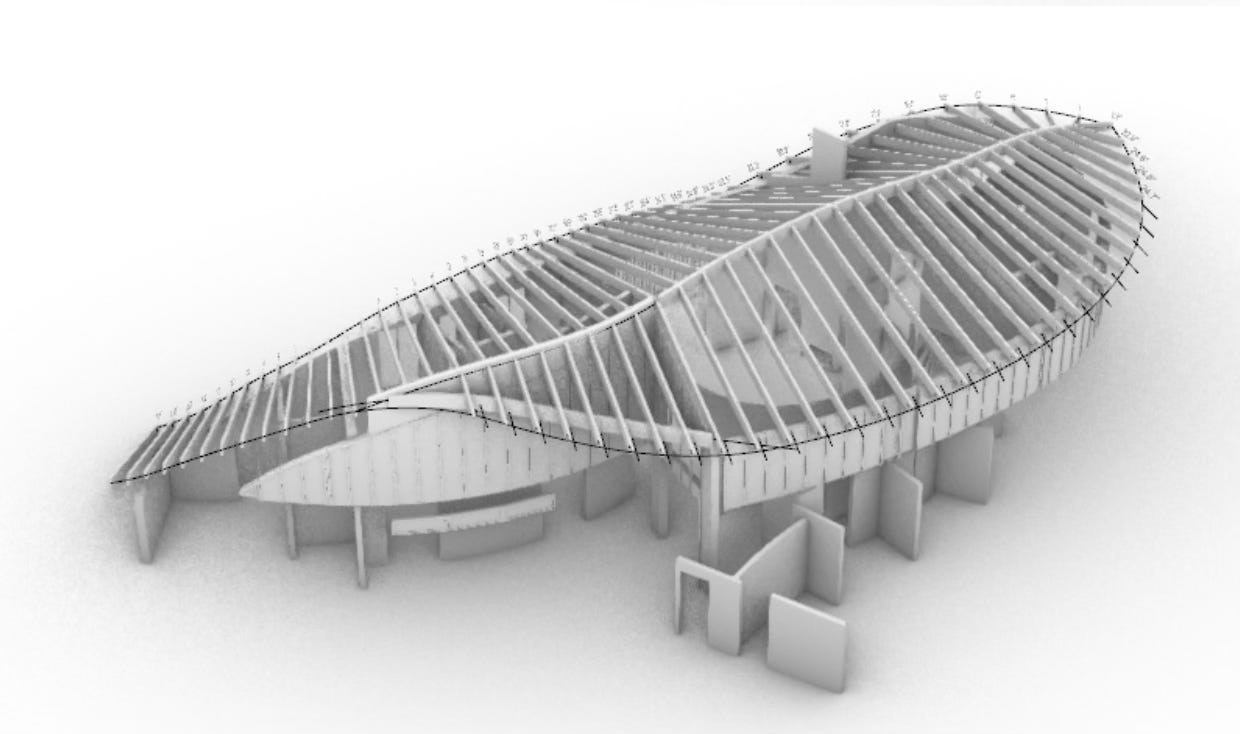

So much is happening here. There is a bit of biomorphism; Tate writes, “We are working with the timber specialists Xylotek on the timber frame of the house, creating a form that mimics the structure of a leaf to visually integrate into its natural setting.”

Here is that carbon cycle again. Plants absorb CO2, while animals eat the plants and release CO2 along with the decomposing plants. Meanwhile, digging up and burning fossil fuels puts vast amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere.

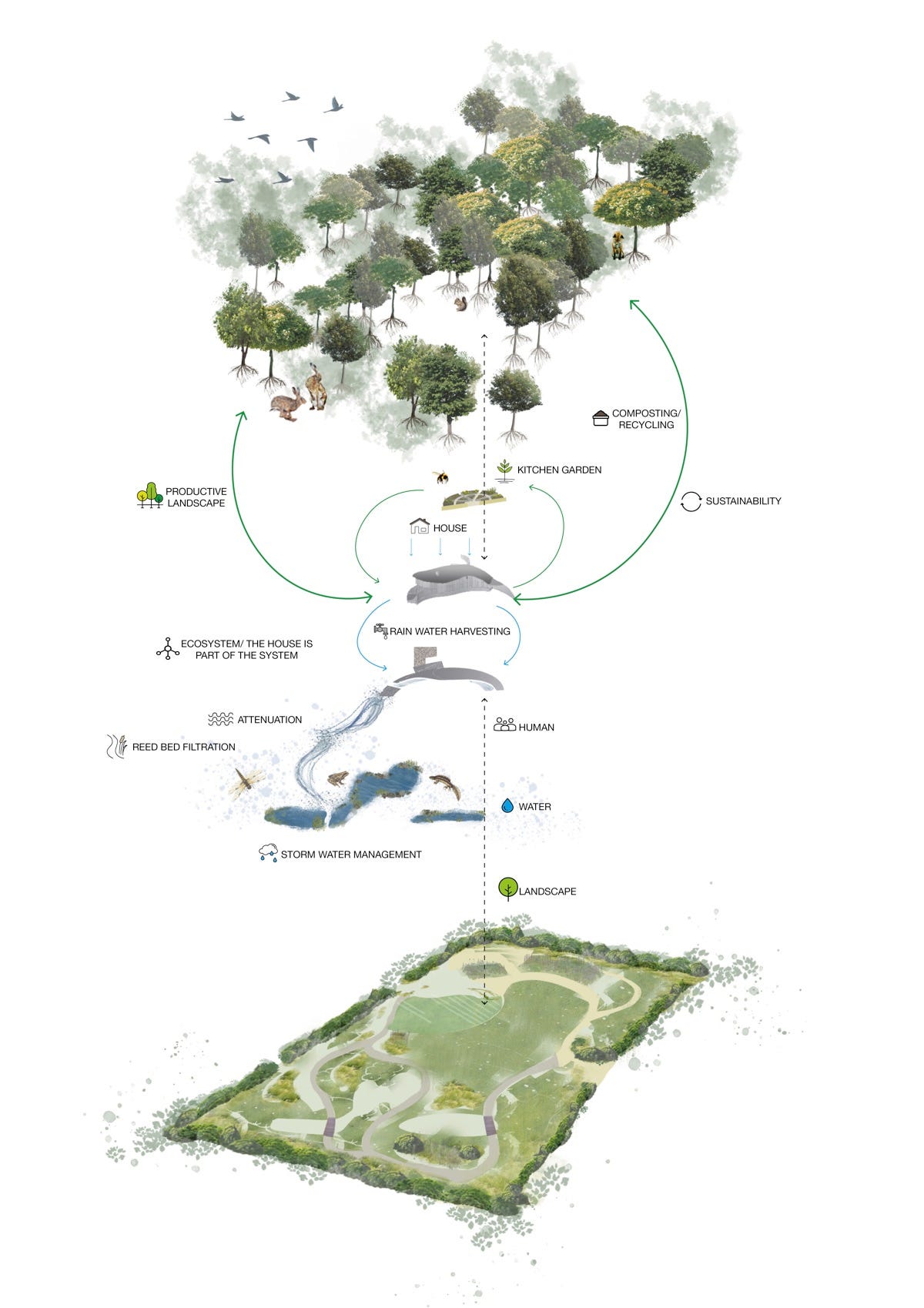

And here is the Serpentine House, looking very much like a carbon cycle without the annoying fossil fuels. There are lots of trees to absorb CO2, a kitchen garden with yet more plants, and no fossil fuels; it is driven by sunshine. The water cycle is also managed.

“A key aspect of the proposal is the integration of the proposed building and landscape to create a symbiotic and sustainable relationship. The emerging landscape design explores how the natural environment can improve building efficiencies, embedding the energy and water management for the scheme firmly into the landscape design, as well as enhancing and improving the existing ecology of the site.”

“We are starting to implement landscape and biodiversity improvements with our experts Applied Ecology. And we are developing an energy and water engineering proposal with Engenuiti and Hoare Lea that will become a ‘closed loop’ system in the landscape, requiring only solar power to drive it.”

“We genuinely believe that by using the principles of regenerative design this project, when completed, will demonstrate how we can live in harmony with nature, creating a positive relationship between people and planet.”

One might point out that this is a 444 square meter (4779 square feet) country house on a lot of land. I would normally say that it doesn’t scale and doesn’t work for much of the population. I have often complained about the massive upfront carbon cost of even the greenest and most efficient but huge Passivhaus or Living Building Challenge homes.

But there are lessons here that can apply to everyone: build from natural materials, grow food, recycle, harvest your rainwater and manage your stormwater. Plant an intensive, productive landscape. Don’t just build a house and bring in services, but make the house part of an ecosystem. Power it with sunlight. These concepts can work at any scale.

This is not a sustainable house given its size, complexity and likely low occupant numbers, a house for the few as opposed to the many. Good intentions, but in some ways greenwashing and a way to allow the use of natural areas for the wealthy. If one looks to Indigenous / historic housing such as a wig wam, round house, sod house, etc, these were truly in tune with their environment, using local materials in a carbon cycle. Smaller structures for more people. Not to say we have to go back to these types, but much of what is professed by Tate's Serpentine House was done for a millennia at less impact, benefiting more people and the environment.

After reading this the first time, my first thought was this is like modern art - a lot of self-justification of an ideology.

I say this is that I didn't see one line, not one line at all, about customer service. Lots about serving an ideology but not one line about serving a customer.

Isn't that THE main purpose of a company? To serve customers?

Same thing with Government - too often, nowadays, I watch and listen to bureaucrats serving their own self-interests instead of being public servants serving their customers.

It's a PANDEMIC, I tell ya'!