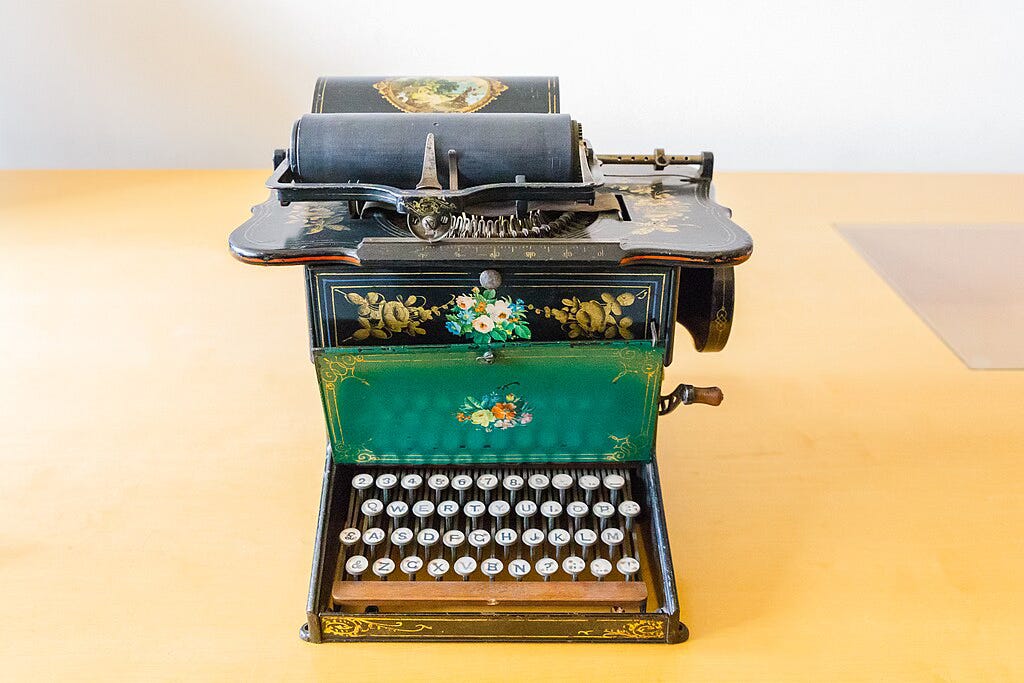

Happy Birthday, QWERTY typewriter

It was patented on this day in 1868, but it had to wait almost until its Bar Mitzvah before anyone wanted it.

Historian Robert Mosher notes that the first typewriter was patented on this day in 1868 by Christopher Latham Sholes, as mentioned in a post by Garrison Keillor. In my book, Living the 1.5 Degree Lifestyle, I wrote that the typewriter was a complete dud; nobody needed it or wanted it. The world had to catch up to it with the Second Industrial Revolution. Here’s an excerpt from the book in honour of the typewriter’s birthday.

Prior to the 1870s, North America was overwhelmingly agrarian, with the population spread far more evenly than it is now, with flourishing small towns popping up everywhere with independent shops serving the local farming communities. When the railways came, they fed into bigger administrative centers, where many were employed as scriveners (copiers) and book-keepers. Offices existed, but they were generally very small.

But two forms of energy changed everything: steam power for the railways and electricity for the telegraph. According to Margery Davies, writing in Woman's Place Is at the Typewriter: Office Work and Office Workers, 1870-1930, this led to “massive consolidation of businesses,” with “giant corporations integrated vertically and horizontally in the merger movement that swept through industry during the 1890s. In the steel, oil, tobacco, food, and meat-packing sectors, to name just a few, such corporations enjoyed virtual monopolies.” Transactions could no longer be handled face-to-face, and accurate records became more important. Davis notes that your small-town butcher might just need simple records, but a big meat-packer needs information from all over the country. Scriveners couldn’t keep up.

As so often happens, technology pops up to fill the need. The typewriter had been around for decades, but nobody would invest in its production because nobody saw the need for it. As Davies writes, “the potential value of a writing machine was not readily apparent to businessmen who ran small offices with a few clerks and a relatively small amount of paperwork.” In 1873, the gun-maker Remington bought the rights to a new typewriter design from the so-called Father of the typewriter, Christopher Sholes, and by 1885, it became a staple of the office. But Davies makes the point that is relevant to almost all inventions, which is that they do not just pop up out of nowhere:

It is clear that in the development of the typewriter, changes in the organization of capitalism gave rise to technological innovation, rather than the reverse. Inventors had been experimenting with writing machines for over 150 years before the Remington company started mass production of the Sholes typewriter. It was only in the 1870s, with the first indications of the expansion of offices and the growth of office work, that any capitalist firm was willing to invest in the manufacture of writing machines. It was not until the 1880s, when offices grew by leaps and bounds, that the typewriter began to sell. Rather than causing change, the typewriter followed in the wake of basic alterations in capitalism.

As the offices flourished, they needed stenographers who could take dictation, and they needed typists. The demand was so great that there were not enough men to do the job (and many didn’t want to be stuck in the same job with little chance of advancement), so companies started accepting women; there were more female and literate high school graduates who were willing to learn how to type, and they got paid less, too. With the industrialization of farming, people flocked to the cities where these jobs were, where women could significantly contribute to the family income.

With typing and carbon paper, there was an explosion in paper consumption and the invention of the vertical filing cabinet, and the need for ever more office space to keep it all handy, central, and accessible. But it all had to be close to where the workers lived, so the elevator was put to work (it had been around for a while too) so that buildings could go up and stack more people more closely together. And in the space of just a few decades, between 1870 and 1910, we pretty much got the cities we have today, with office buildings and apartments and suburbs, subways and streetcars, all running on coal and steam and electricity and telephone wires.

This is an example of why you cannot separate how we live from how we work and how we get between the two, and how you can’t deal with one aspect of our lives without dealing with the others. Look what happened when gasoline became the transportation energy of choice, eclipsing steam and electricity.

Special offer!

I do not want to put up a paywall on this site, but it provides a meaningful portion of my income. So here’s a limited-time offer: I will send a signed copy of the print edition of “Living the 1.5 Lifestyle” to anyone in the USA or Canada who signs up for a one-year subscription (C$50, cheap at about US$35 ).

I'm still strongly persuaded that we achieved the summit in word processing technology with the IBM Selectric III electric typewriter with the self-correcting ribbon feature. Everything since then has added complexity and challenges and an incredible explosion of 'written' communication while making no significant improvement in the content.