Happy 125th Birthday, Alvar Aalto; We are still learning from you

An early master of healthy buildings, full of light, air and openness.

These days, with Covid still floating around, people want lots of fresh air in their homes and offices. Surfaces that are easy to clean. A little space and separation from our neighbour or co-worker. The building scientists have been saying since Covid started that it’s airborne and that good ventilation is the answer; the epidemiologists said it was transmitted by droplets that settled within six feet, so everything should be disinfected and washable. In either case, building science, architecture and interior design have a powerful role to play in keeping people healthy.

A hundred years ago, another disease was killing people: tuberculosis. Unlike Covid-19, there was no vaccine. People had known about germ theory since 1882, when Robert Koch identified that tuberculosis was caused by a bacillus, but they didn’t have antibiotics or effective drugs. When someone got TB the prescription was isolation, rest, fresh air and sunshine, often in sanatoriums built for the purpose.

One of the most influential and important was the Paimio Sanatorium, designed by Alvar and Aino Aalto in 1929, when TB was the most important single cause of death in Finland. It’s one of the original healthy buildings and still has much to teach us if we would pay attention.

The Aaltos called Paimio an “instrument for healing.” Aalto also noted that ‘The main purpose of the building is to function as a medical instrument.’ They designed everything- the furniture, the tableware, even the sinks in the rooms. According to Riccardo Bianchini writing in Inexhibit, even the ventilation system was designed to defeat disease.

“Since fresh air was part of the patients’ treatment, the Aaltos also designed an ingenious natural ventilation system that exploited the difference of pressure between the wing’s lower and the upper floors, complemented by more traditional opening windows and electrical exhaust vents. The use of natural ventilation over a centralized mechanical ventilation system was preferred mainly to avoid the possible spread of infectious bacteria through common ventilation ducts. The rooms were also equipped with a radiant-ceiling heating system.”

The furniture was designed to be easy to clean and to leave no place for bacteria to hide. The beds were tubular steel; the famous Paimio chair, still in production, from laminated wood and molded plywood.

According to Ellis Woodman in the Architectural Review,

“The most ample evidence of Aalto’s attention to detail was to be found in the wards of which only one now survives in its original form. Their principal innovation was their scale: accommodating two patients each, they were significantly smaller than the norm. However, the architect’s care for the wellbeing of patients was imprinted on every last component of these intensely conceived interiors. In response to Finland’s punishing winters, each window was designed as an assembly of two individually framed layers separated by a wide gap. The offsetting of their opening casements enabled ventilation to be introduced without generating a draft.”

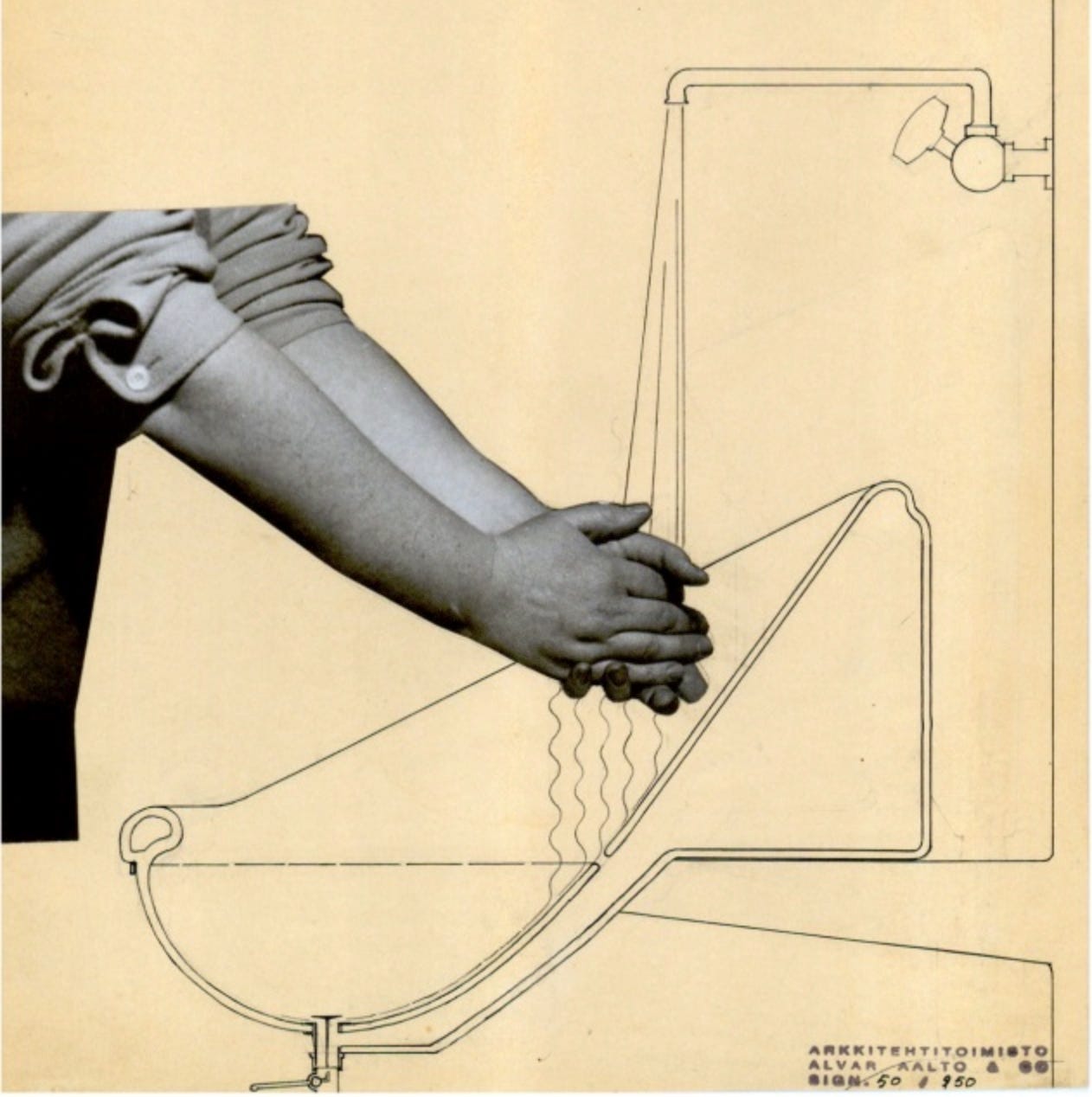

The sink that Aalto designed for the rooms is particularly interesting. Today sinks are designed to look good, rather than for function.

“no noises, no water splashes when washing your hands in running water, because the basin-china is in a position of 45 degrees.” It is also self-cleaning because of the slope.

Even the use of colour was unusual; the Aaltos worked with artist Eino Kauria to pick different colours for different moods. Yellow was for the main communal areas, red in the dining areas, with soothing blues and greens in the patients rooms.

The late architectural historian Paul Overy wrote in Light, Air and Openness:

“Sanatoriums exerted a powerful hold on the imagination of modern architects and designers as building types and institutional models. Among the first to be designed in in “modern” or “modernist” style, purpose built sanatoriums for tuberculosis and other chronic diseases were some of the most technologically advanced buildings of the first decades of the 20th century. Combining associations of health, hygiene cleanliness (and easy-to-cleanness) modernity and machine like precision of operation, they were to have a major influence on modernist architecture and furniture design between the wars.”

It should still be an influence today, with spaces that Overy describes as “designed not only to be easy to clean but to appear to be spotlessly clean- potent visual symbols of hygiene and health.” We should also remember Aalto wasn’t designing for the rich, but for everyone.

“We should work for simple, good, undecorated things, but things which are in harmony with the human being and organically suited to the little man in the street.”

There are not a lot of Aalto quotes, probably because of his most famous one: “I do not write, I build.”

Happy 125th Birthday, Alvar Aalto.

That's really interesting to know that they put so much thought into a sanatorium. Should all medical buildings be so thoughtfully designed, that would be fantastic!