From the archives: It's the Ides of March, a Good Day for a Bath

A call for the rebuilding of public baths.

This post was written for Treehugger but has been deleted there, so I reconstruct it from the internet archives.

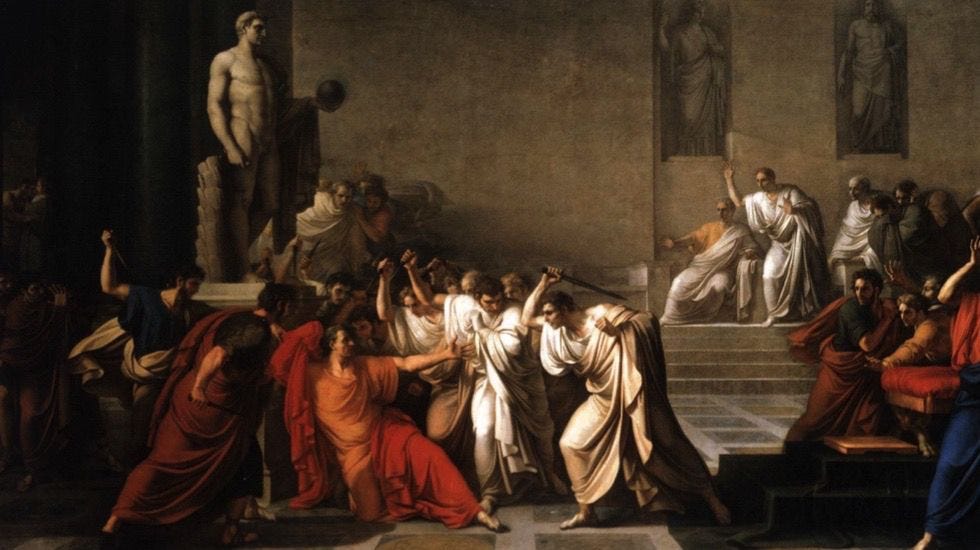

It's the Ides of March, made famous by Shakespeare; every month had its Ides, usually the 15th of the month. But he put those famous words into the mouth of a soothsayer, warning Caesar: "Beware the Ides of March." And so on or about March 15, 44 BCE, Julius Caesar was stabbed in the rotunda, which as Canadian comic Johnny Wayne noted, has gotta hurt. But when Roman senators weren't hanging out with knives in the Rotunda, they hung out with towels in the public baths, and I never miss an excuse to talk about baths.

The baths in Rome were a lot more than just a place to get clean; they were a social institution, a key part of Roman life. Bathing was considered essential for health and wellbeing, for regeneration. The question arose then and throughout history, like it does now in the discussion of health care: Is this the role of the state? Siegfried Gideon writes in Mechanization takes command:

The role that bathing plays within a culture reveals the culture's attitude toward human relaxation. It is a measure of how far individual well-being is regarded as an indispensable part of community life. This is a social problem. Should society assume responsibility for guarding health and promoting well-being or is this a private matter? Is it a duty of the state to provide the agencies of relaxation regardless of the cost? Or should it regard its people as mere components of the production line, leaving them to their own devices as soon as they have finished their work?

The baths were primarily for bathing and exercise, but also for reading, meeting and doing serious politics, like Caesar and Crassus did in the movie Spartacus. According to Gideon:

The Roman workday began at dawn, and normally ended at one or two o'clock. The thermae [baths] opened at noon. One visited them at the close of work before the main meal.

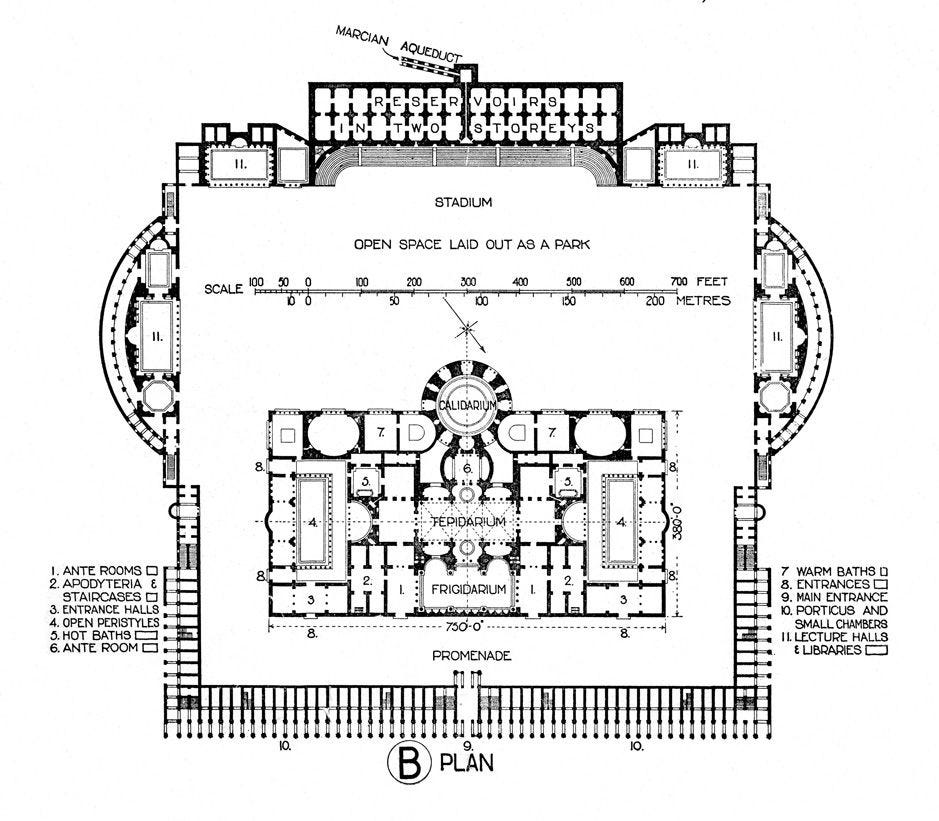

You arrived and changed in the apodyterium, then took exercise in the palaestrae. Then you went through a series of rooms; first, the notatio, a big open air swimming pool with cool water. Then you moved to the laconica and sudatoria, saunas and steam rooms. Then it’s off to the calidarium, a hot room, after which you hang out in the tepidarium, a warm but comfy room, probably where Crassus and Caesar were hanging out. Then it’s a jump into the Calidarium, a cool room that’s actually the biggest and most dramatic. Finish off with a massage, take in a lecture or read a book in the library and you are probably ready for dinner or bed.

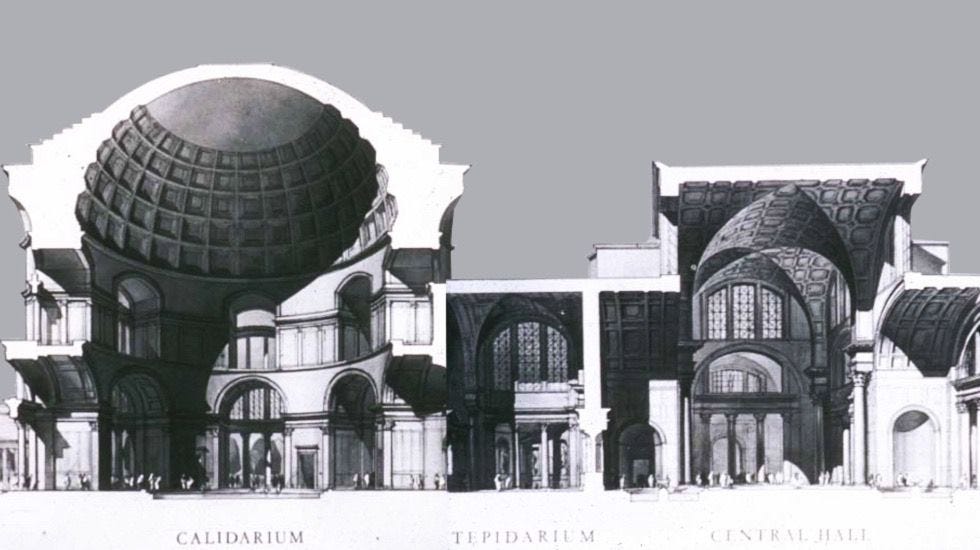

Here is a section through a reconstruction, showing the scale of the spaces.

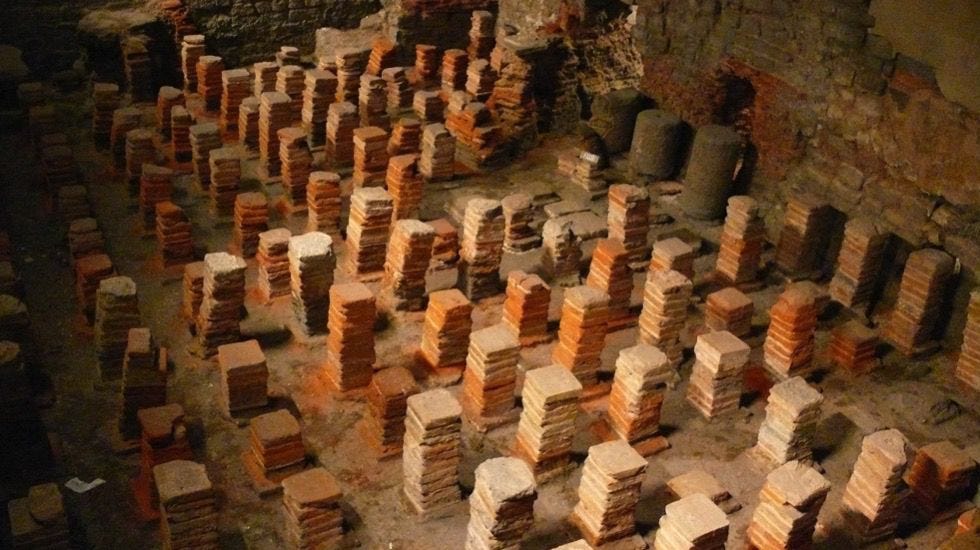

The baths were toasty wherever they were built, often with floors raised on pillars so that hot gases from fires could flow underneath. It consumed huge amounts of wood and water, which was heated in giant lead boilers and delivered in lead pipes.

So what happened to the ritual of bathing? In Rome, they kept it up as long as possible; Gideon writes:

The cutting off of the Roman water-supply when the nomads destroyed the Campagna aqueduct at the wane of the Empire has told upon our cultural life down to the present day.

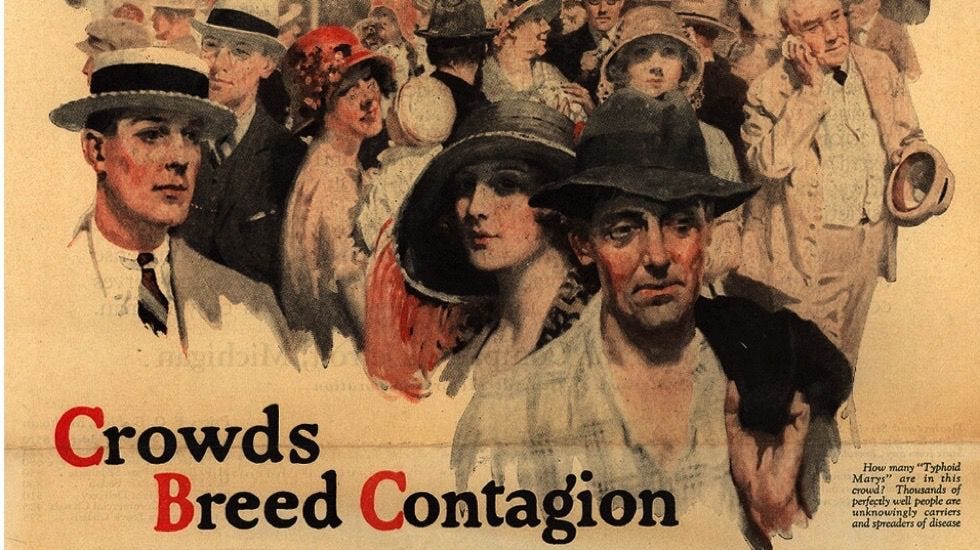

Bathing didn't disappear; the Arabs and Turks kept up the bathing tradition, but the Christians did everything they could to kill it. According to Coming Clean:

Christian religious authorities often disapproved of bathing because of the unnecessary indulgence and focus on earthly pleasure rather than spiritual purity and because experience showed that, at least among the elite, it often led to sexual misconduct.

Even the medical advice of the time recommended against bathing too much:

It was medicine not morals, however, that virtually ended bathing in western culture. Medical theories disapproved of bathing for hundreds of years because they considered it harmful, even dangerous. If disease was spread by bad air, and water opened the skin to air, it was clear that people should not wash often and certainly should not submerge their whole bodies in water. A layer of dirt on the body was sometimes considered a prudent protection against disease.

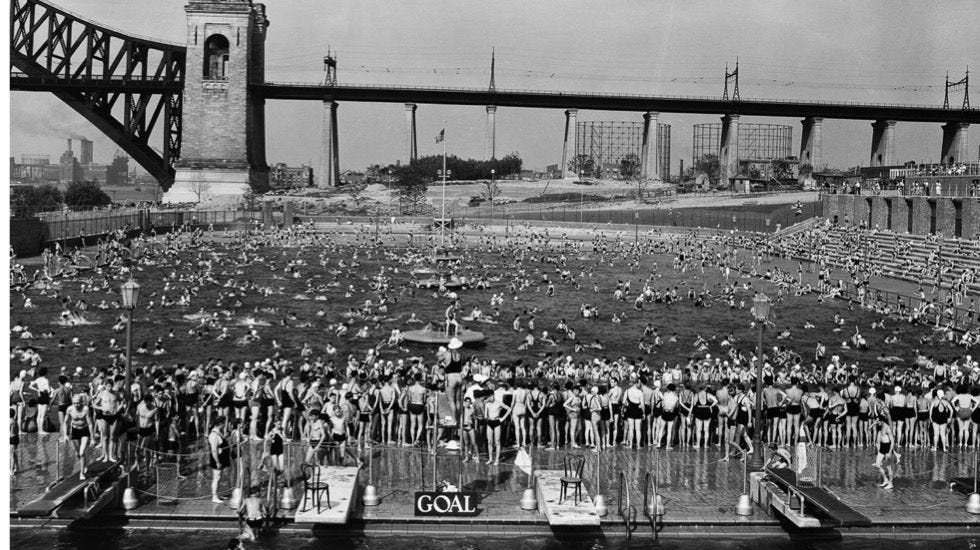

Public bathing became popular again in cities as pools were built for public recreation, but many of these closed down in the 50s because of the polio scare.

Parents were instructed to keep their children well bathed, well rested, well fed, and away from crowds. Bathing suits were locked away in closets, and nobody went to the public pools. When polio struck, movie theaters were shut, camps and schools were closed, drinking fountains were abandoned, draft inductions suspended, and nonessential meetings were canceled until the epidemic appeared to be over for the time being.

It has taken decades for it to return. It is all such a shame; the Romans were really on to something. Bathing should be fun, social, a thing to do. Something to think about on these Ides of March.

loved this

Off-topic but the last bit about school closures related to fear of the polio virus sent me down a rabbit-hole where I stumbled across this interesting 1993 CBC documentary that highlights Canada’s crucial contribution to the development of the polio vaccine: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/closures-equipment-shortages-and-insights-from-canada-s-polio-invasion-1.5517204

Also, with regards to pool closures in the US prior to the polio scare, see: https://daily.jstor.org/when-cities-closed-pools-to-avoid-integration/