Ephemerality: Another radical design concept for the climate revolution

Revisiting Bucky Fuller's term for doing “more and more with less and less until eventually, you can do everything with nothing.”

It’s that time of year when I prepare for another term teaching Sustainable Design at Toronto Metropolitan University’s School of Interior Design and Creative School. For the last few years, I have concentrated on four main themes, which I have often discussed in my posts:

Radical Efficiency – Everything we build should use as little energy as possible.

Radical Decarbonization – Why we need to build out of natural, low-carbon materials and electrify everything.

Radical Sufficiency – What do we actually need? What is the least that will do the job? What is enough?

Radical Simplicity – Everything we build should be as simple as possible.

But while writing my new book, The Story of Upfront Carbon, (coming from New Society Publishers in early 2024), I concluded that four concepts were not enough, and I came up with about ten more and devoted a section to each. One of my favourites is Ephemerality. Here is a taste of it:

A dozen years ago, Treehugger founder Graham Hill started LifeEdited, designing small apartments with moving walls and Murphy beds. I was shocked to find no stove in the kitchen; Graham pulled a portable induction cooktop out of a drawer. If he was having a party, there were two more; he would take out what was needed when needed. His kitchen stove had been ephemeralized.

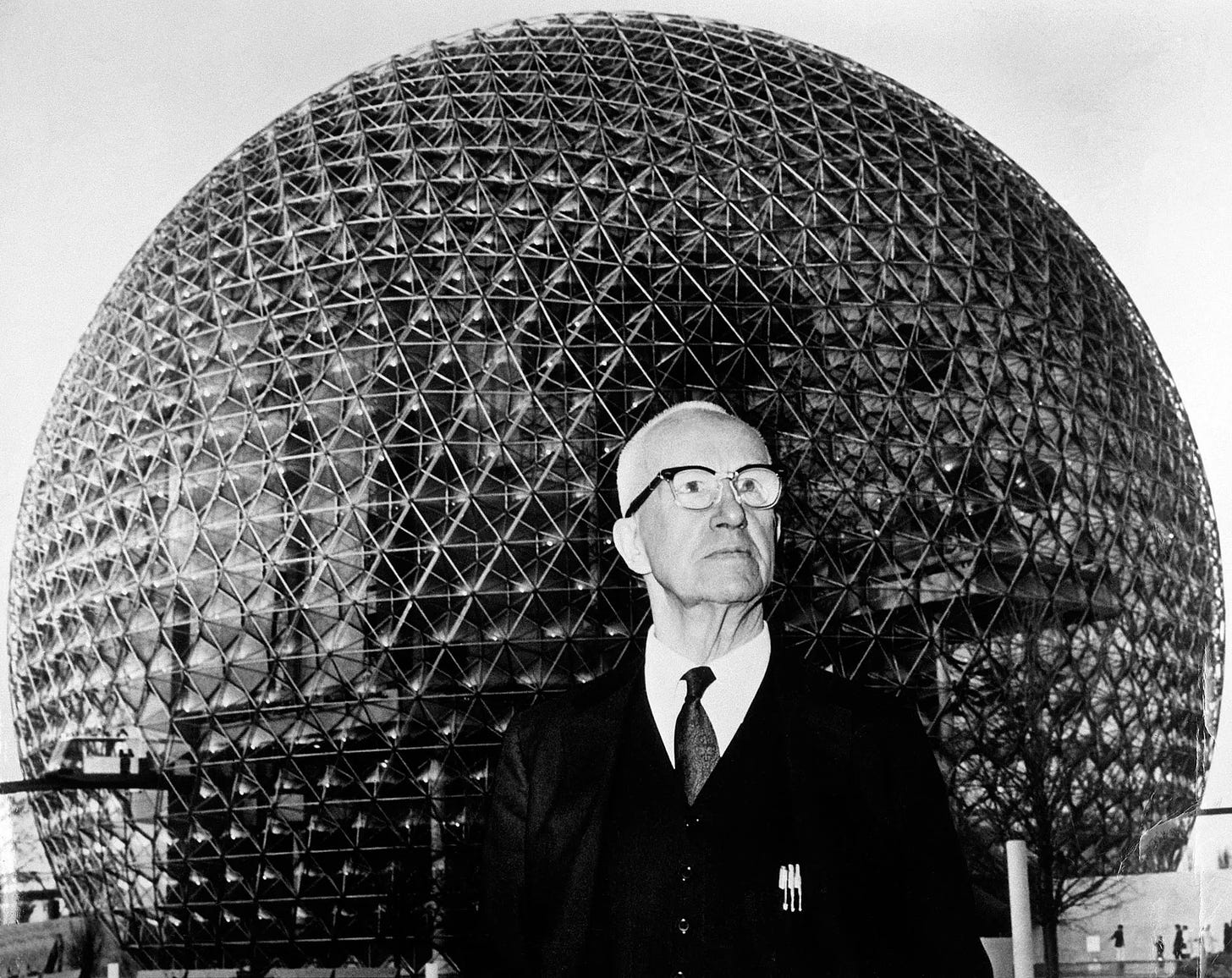

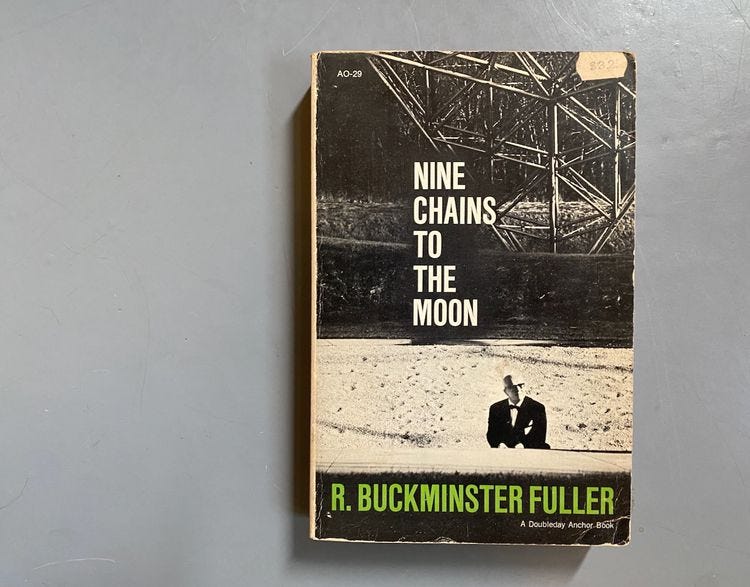

Ephemeralization is a term invented by R. Buckminster Fuller in his 1938 book Nine Chains to the Moon to describe how, through technological advancement, we can do “more and more with less and less until eventually, you can do everything with nothing.” He concluded:

Efficiency = doing more with less.

∴ EFFICIENCY EPHEMERALIZES.

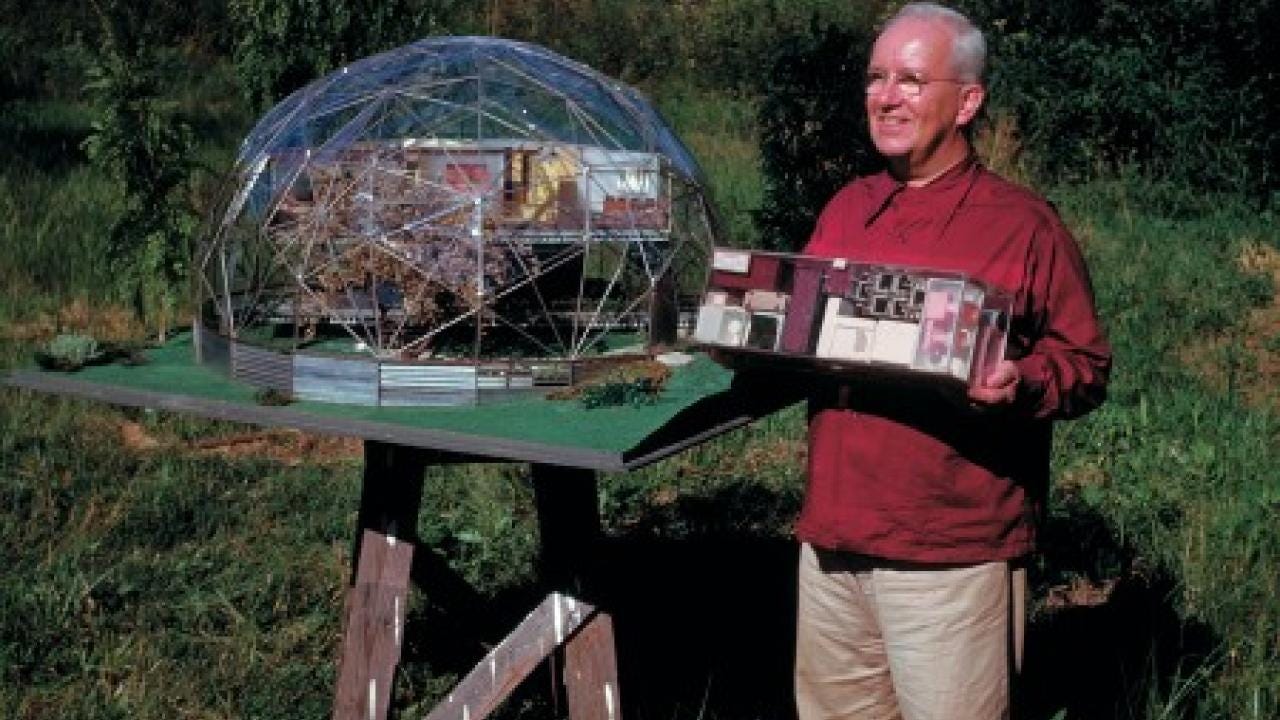

This was the thinking behind the form and the structure of his geodesic dome; a sphere encloses the most volume relative to the surface area, and the tensegrity structure that Fuller invented used the least amount of material to enclose the sphere.

We are all living in a world of ephemeralization, the best example being that smartphone in your pocket; thirty years ago, it would have taken an entire Radio Shack store’s worth of equipment to do what it can do, which is why we no longer have Radio Shacks. The only device on the entire page that is not in my phone is the “tiny dual-superhet radar detector.” (Oh wait- there is even an app for that.)

Retired Buffalo journalist Steve Cichon found this 1991 ad and totalled the cost of everything at $3,054.82, which, in today’s dollars, is $6,856.32. And people think iPhones are expensive! Apple says the upfront carbon in an iPhone is 80 kilograms, but imagine how much upfront carbon is in all the stuff in that ad, and how much space it all takes up, what resources it took to make it all, and how much electricity it takes to operate, compared to the 6.65-ounce phone in my pocket. That’s the wonder of ephemeralization.

Ephemeralization is a form of sufficiency: How do you do more with less and do it better? Let’s look again at the kitchen stove. In the mid-1800s, it revolutionized cooking, as the flat-pack box made from six plates of iron allowed multiple dishes to be cooked at once, heated the home, and saved women’s lives as “hearth death” was the second-biggest killer of women after childbirth.

It evolved into a heavy cast-iron stove that did everything, from heating the room to boiling water. Since the heat came from a single source, putting the oven and cooktop together made sense.

When gas and electricity replaced wood, there was some experimentation with putting components at convenient heights, but generally, the stove remained a hot box with the cooking surface on top of the oven, even though they were powered separately, and even though it was known that bending down to get stuff out of the oven was not as convenient or safe. (See my post: Why are kitchen counters 36 inches high?)

Now we are going through another cooking revolution, where the oven and the cooktop don’t even use the same technology, and there is no good reason to put them together, unless, as in our house shown here, you are replacing an existing appliance and don’t want to renovate the kitchen. Then you find that putting them together is a marriage of inconvenience, where the oven’s heat rises and heats the induction section and will probably lead to its eventual demise.

Meanwhile, companies such as Italy’s Fabita are selling induction hobs you hang on the wall and take down as needed. Others are going halfway, using tiny two-burner cooktops and keeping spare portable units for the occasional times they need more. What was once the dominant feature in the kitchen has been ephemeralized.

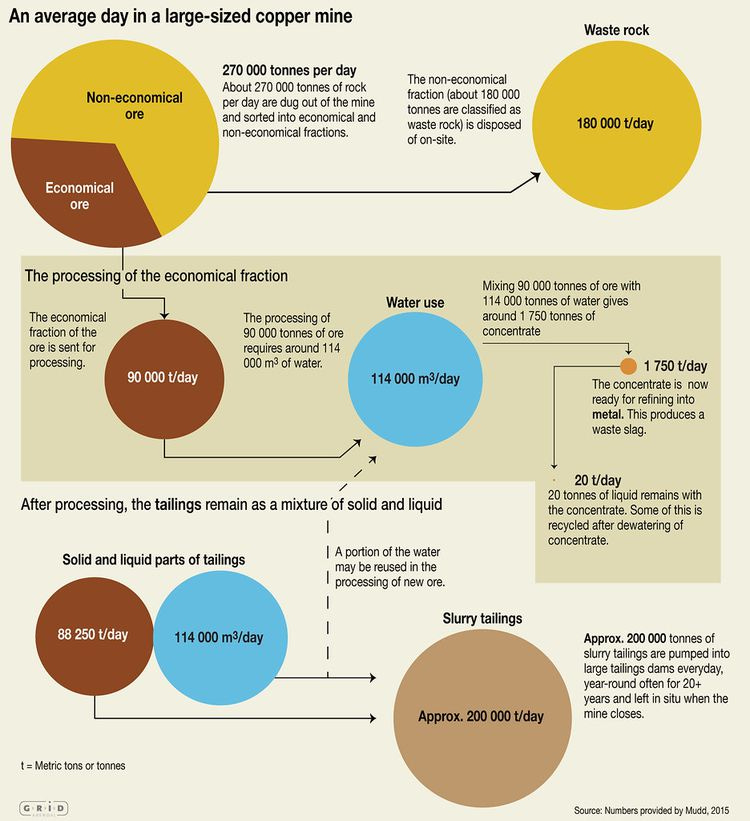

Ephemeralization is going to be key to getting through the next few years as we electrify everything. Take copper; it is in almost everything that is electric, and we are going to need a lot of it. Consultancy BloombergNEF “expects that primary copper production can increase about 16% by 2040. That increase, needless to say, is rather short of demand. By the early 2030s, copper demand could outstrip supply by more than 6 million tons per year."

Our homes have an average of 195 pounds of copper wiring. According to Copper.org, "There is an average of 50-55 electrical outlets per home and some 15-20 switches. That translates to between 2½ and 3 pounds of copper alloy for these uses per house." Yet, in the age of LEDs and electronics, how many of these are actually connected to a device that requires 14 gauge wiring carrying 15 amps? Perhaps four big appliances; everything else is running on milliamps now, and probably three-quarters of that copper wiring could be replaced with USB or network cables.

Then there are electric cars, with an average of 183 pounds of copper. This could be the biggest driver of the demand for the stuff, but as we have noted many times, e-bikes can eat cars and have 1/300th of the copper and lithium. Of course, e-bikes don't work for everyone, but they could for many people most of the time, especially if there was an investment in safe places to ride and secure places to park. Throw in decent planning, 15-minute cities, and walkable communities, and you have ephemeralized transportation.

Then there is the infrastructure we need to power our all-electric renewable world. According to the Copper Development Association, solar photovoltaic systems consume 5.5 tons of copper per megawatt. Onshore wind power takes 7,766 pounds per megawatt, and offshore wind, an astonishing 21,067 pounds per megawatt, mostly due to the cabling. Maybe we should be thinking of how to reduce demand instead of just electrifying everything.

Ephemeralization differs from sufficiency in that it isn’t just about using less; it is about doing things differently. In my book, I quote geologist Simon Michaux:

“The existing renewable energy sectors and the EV [electric vehicle] technology systems are merely stepping stones to something else, rather than the final solution. It is recommended that some thought be given to this and what that something else might be.”

Ephemeralization is all about going back to first principles and redesigning our world to this new paradigm where we consume fewer resources and less energy, thinking like Bucky did. Perhaps two wheels are better than four, perhaps five volts DC is better than 120 volts AC, and perhaps we no longer need so many duplicated spaces for living and working. Actually, Bucky Fuller had something to say about that too:

“Our beds are empty two-thirds of the time. Our living rooms are empty seven-eighths of the time. Our office buildings are empty one-half of the time. It’s time we gave this some thought.”

This is great Lloyd, thank you. What a fun and thought-provoking post. The Radio Shack ad is an amazing example of ephemeralisation but isn't it also an example of Jevons paradox? As in, I never would have owned most of those things back in the day but as they get cheaper and cheaper they get added on and added on. Surely not enough to outweigh the carbon benefits of making them digital of course. But then surely the answer is a kind of combination of Sufficiency and Ephemeralisation? And speaking of sufficiency, here is a video a colleague shared with me today: The CEO of Veolia, a mammoth Energy, Waste and Water company, extolling the virtues of sufficiency: https://youtu.be/K_ibNuZAbbM - at least in France it seems to be more and more mainstream but I cannot help but doubt the sincerity of many of pick up the mantle.

Having one burner is a sure sign of someone who doesn't cook much. I camp (a lot, making real meals) on two burners for a family of four (and frequently for others too), and I shudder at the thought of doing that year-round. I'll keep my four-burner induction range, thanks. Low-carbon paths to simplicity can be found in many, many other areas of life, including smaller footprints on high-performance homes, taking a pass on almost all electronics and gadgets — and cooking real meals at home from locally sourced ingredients. Thanks for your always thought-provoking posts!