Eddie Bauer, American exceptionalism, and the story of the puffer jacket

The chain is bankrupt again, and maybe this bit of history will die with it

The Eddie Bauer chain is dying, and I hope the myth that Eddie Bauer invented the down puffer jacket will die with it. I wrote about the history of the puffer jacket in my book, The Story of Upfront Carbon, because it is such an interesting tale about doing more with less. Here’s an excerpt:

The puffer jacket is the epitome of ephemerality; there is nothing to it, a bit of parachute fabric and down or light synthetic insulation. It weighs almost nothing and squeezes down to fit into your pocket. It’s a fascinating story of how smart, minimalist design can do a better job with less stuff.

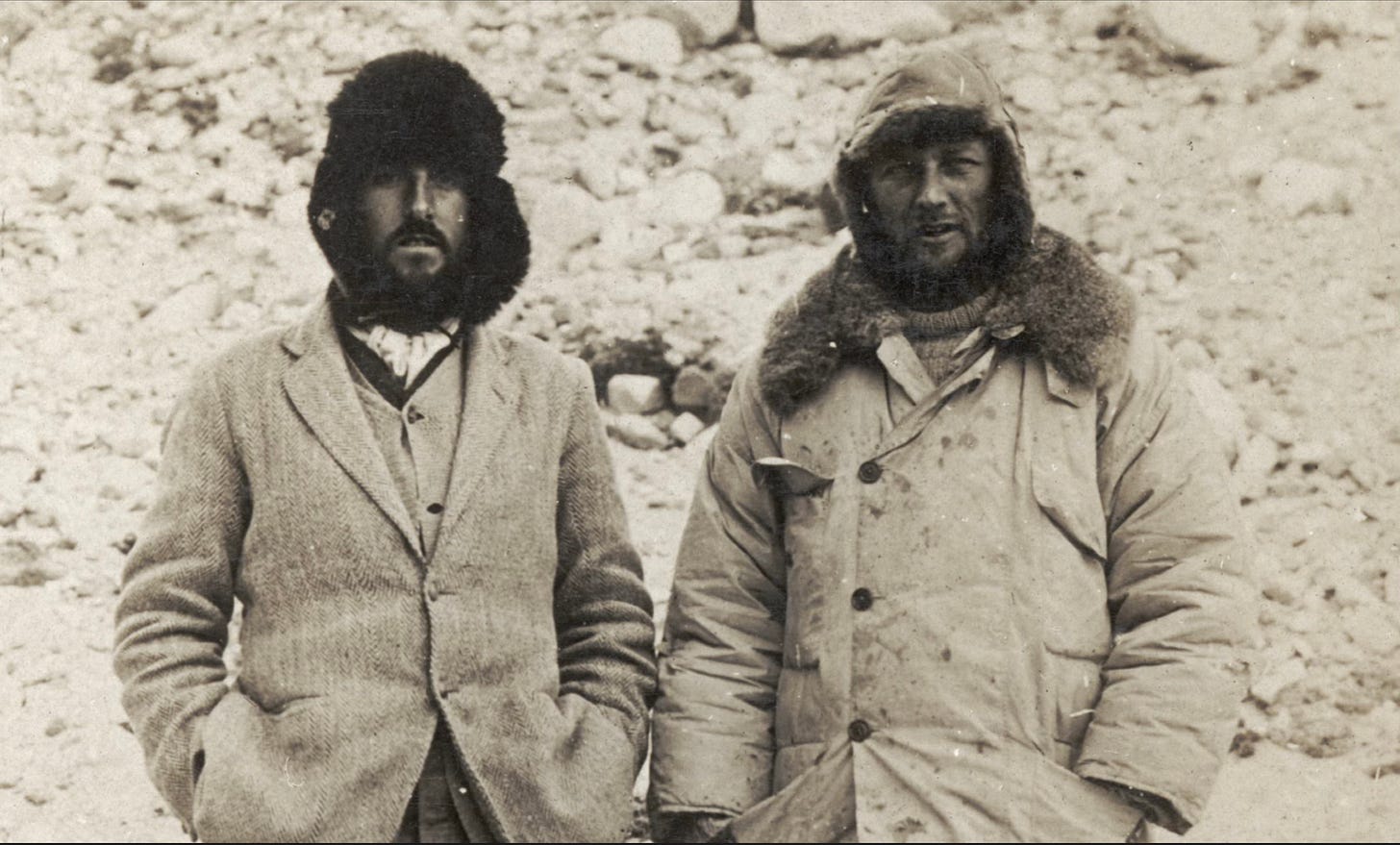

The puffer was invented by George Finch, a brilliant Australian chemist and mountain climber, considered one of the two best in the world, along with George Mallory. The two were part of a 1922 expedition to Mount Everest, where Finch showed up in what he called his eiderdown coat, made of bright green hot air balloon fabric. The other climbers all wore cotton and tweed and considered Finch’s outfit a joke. The expedition secretary wrote, “They have contrived the most wonderful apparatus that will make you die of laughing.” One can imagine him taking the abuse and quoting the most famous line from his son Peter Finch’s film career: “I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take it anymore!” Instead, he outlasted the skeptics, writing later: “Everybody now envying … my eiderdown coat, and it is no longer laughed at.”

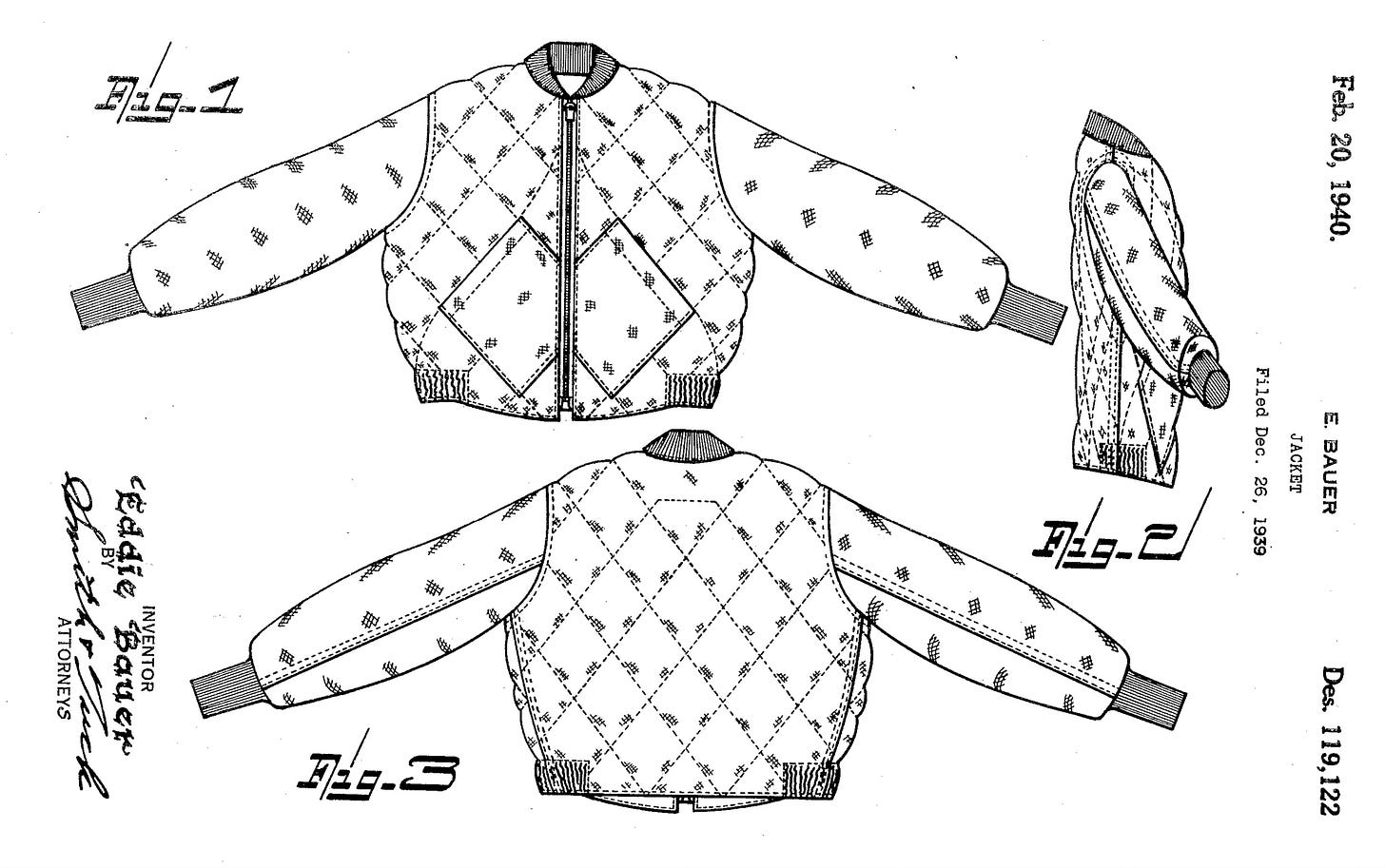

In 1936, Eddie Bauer developed the Skyliner quilted down jacket after almost freezing to death on a fishing trip. At 21 ounces, it was marketed as “lighter than feathers, warmer than ten sweaters.”

Of course, if you look at most American websites, you will learn that Eddie Bauer invented the puffer jacket. This always bothered me; in the USA, nothing matters if it’s “not invented here.” So the puffer jacket joins the light bulb, the telephone, and the television as American inventions, even though they were, respectively, English, Canadian, and Russian.

Today, puffer jackets are everywhere. They are what Financial Times writer Robert Armstrong calls “Gorpcore.”

Gorpcore—functional outdoor clothing worn for everyday rather than to stay warm and dry in the elements—turns out to have an alpinist’s endurance. It was first noticed in the wild six or seven years ago, its ascent roughly coinciding with camping-chic runway shows from Prada and others. Puffer coats, Patagonia fleeces and technical-looking shoes have been seen in New York bars ever since.

When I first read Armstrong’s quote there, I didn’t understand it. People wear functional clothing every day because it keeps them warm and dry in the elements. I have been wearing it for decades. Freud supposedly said, “Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar,” but evidently a puffer is more than just a puffer.

Morweena Ferrier of the Guardian suggests that it is environmental signalling:

“There is something in flagging your allegiance to clothes traditionally worn outdoors. It is not simply that hiking and camping have a virtuous reputation-you hike, therefore you care about the environment.“If you ski, you are probably rich.’It is a coat favoured by winter-sport enthusiasts, who tend to be affluent.“The function attracts the wealthy, who imbue the puffer with lifestyle status.”

I sometimes feel guilty about wearing a puffer filled with down instead of some of the alternatives, such as polyester, but the totally disinterested International Down and Feather Bureau has a life cycle assessment prepared by a reputable third party, which concludes that down has “eighteen times less impact on climate change than polyester fill.” Polyester is a solid fossil fuel, so this should not be surprising compared to a natural product. They also claimed that “on a per ton basis, down has an 85% – 97% lower impact than polyester in all categories analyzed.” I thought this might be silly to do a comparison on a “per ton” basis, given how light down is, but they compared material with the same CLO value, a measure of how well clothing insulates. One hundred eight grams per square meter of down has the same CLO as 230 grams of polyester, so while the “per ton” comparison is not as bad, it is still relevant. As is common outside the construction industry, the life cycle assessment is thin and more of a summary, and it doesn’t give hard numbers. But I feel less guilty about down from an environmental point of view.

Feeling guilty about down from an animal welfare point of view is another story. Some of it comes from geese raised for foie gras, which involves force-feeding to fatten the liver and is cruel. Others come from live-plucking, which is painful. Ninety percent of down comes from China, where duck is a common meal.

Patagonia has developed its own Advanced Global Traceable Down Standard (TDS) that other brands could sign up to. Alas, they appear to be on their own. “Though we continued to advocate for other brands to begin sourcing Advanced Global TDS–certified down, no major brand ever did, despite continued efforts.”

Other companies adhere to a Responsible Down Standard (RDS) that certifies birds “have not been subjected to treatments that cause pain, suffering or stress and that an identification and traceability system that applies to the origin of the material is applied and maintained.” Companies also note:

Down, feathers, and hides must be by-products of the food industry;

The use of down and feathers obtained by live plucking of animals is prohibited;

The use of down and feathers from the foie gras industry is prohibited.

PETA doesn’t believe any of this and has exposés on its website of certified “responsible down suppliers” demonstrating animal cruelty. “The RDS is a veil of false assurances about animal welfare that does little or nothing to protect the animals who continue to be exploited and killed for profit.”

This makes it all a very hard choice. From an upfront carbon point of view, down is clearly superior to polyester. It’s also functionally better, at half the weight for the same amount of warmth and a lot more compressible when packing it away. And we haven’t even gotten started on the problems of microplastics that are shed from polyester clothing products and what they are doing to the marine environment.

Patagonia is expensive. My UNIQLO down jacket is filled with RDS-certified down. Vegans and PETA say we shouldn’t be benefiting from the slaughter of animals. But this seems to be one of those cases where, from an environmental and especially an upfront carbon point of view, responsible down wins hands down.

Then there is the fabric that encloses the down. Almost all puffers are made with polyester fabric. Patagonia uses recycled polyester and has started using “prevented ocean plastic,” which is collected from coastlines that lack waste management infrastructure. “For the Spring 2023 season, 87% of our polyester fabrics are made with recycled polyester. As a result of not using virgin polyester, we avoided emitting more than 4.4 million pounds of CO₂e into the atmosphere.”

Many other companies claim to use recycled polyester from PET bottles, but there’s a catch; according to one study, making polyester from recycled plastic has ten times the carbon footprint of virgin polyester. “The total CF of recycling processes was much larger than that of virgin production processes. This was caused by a series of energy intensive procedures (e.g., crushing, high temperature cleaning and drying) involved in the spinning stage from waste polyester bottles to recycled polyester fibers.”

Wait, there’s more. The Changing Markets Foundation claims that recycling polyester from bottles into fabric is not sustainable or circular because “PET bottles should be kept in a closed-loop recycling system for food contact materials.” The only truly circular polyester strategy is “fiber to fiber” where it is made from clothing; otherwise, the PET bottle companies have to buy virgin plastic to replace what was turned into clothing.

The puffer jacket wraps up so many of the issues of sustainability in one warm coat. From a design efficiency and ephemerality point of view, it is brilliant, doing so much, so well, with so little. From an information point of view, we have so many companies saying they are measuring their impact and so little real hard data for a product with only three components (fill, jacket, zipper). Only Allbirds tells us what we want to know: 20.9 kg CO2e emissions. We have to weigh animal welfare against embodied carbon against marine environment welfare. We even have to decide whether we like recycled water bottles or demand recycled fishing nets. It is all so complex, all about a relatively simple product.

Insight: In the end, we come up with the same answer every time, whether it is my coat or my computer:

Buy nothing and make do with what you have.

Buy secondhand.

Buy high-quality and make it last. (Hello, Patagonia!)

Re: recycling plastic bottles. We can all get by without bottled water. That's an easy example of "buy nothing."

This morning I wore a jacket a friend gave me because he outgrew it, 50 years ago. It is a polyester puffer jacket. On my bike ride yesterday I wore an Eddie Bauer jacket my father handed down. He bought it 20 years ago and is now 99. I do have other jackets that violate the rules, but their zippers break. To replace the zipper would cost more than the jacket costs new. That 50 year old jacket still works. Your three rules are excellent.