Did Virgin's transatlantic flight really use 100% sustainable aviation fuel?

It's not sustainable; there just aren't enough dead cows, and there is not enough land to keep us all up in the air.

The press release is titled Virgin Atlantic flies world’s first 100% Sustainable Aviation Fuel flight from London Heathrow to New York JFK. Richard Branson says, “The world will always assume something can’t be done, until you do it.”

The British Minister of Transport, who subsidized the flight, says, “Today’s historic flight, powered by 100% sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), shows how we can both decarbonise transport and enable passengers to keep flying when and where they want.”

The Minister’s comment raises two questions: 1) Is this fuel really sustainable? 2) Will it enable passengers to keep flying when and where they want? I have been writing about SAF for a number of years, and I believe the answer to both questions is no.

First of all, we have to look at the word “sustainable,” defined by the United Nations Brundtland Commission as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” Does this fuel meet that test?

The release describes the fuel:

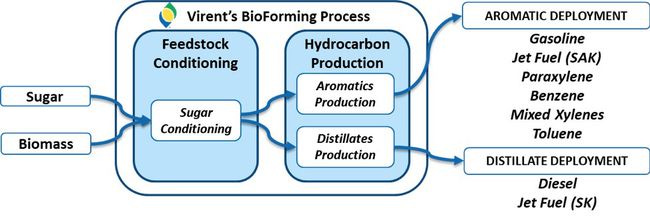

The SAF used on Flight100 is a unique dual blend; 88% HEFA (Hydroprocessed Esters and Fatty Acids) supplied by AirBP and 12% SAK (Synthetic Aromatic Kerosene) supplied by Virent, a subsidiary of Marathon Petroleum Corporation. The HEFA is made from waste fats while the SAK is made from plant sugars, with the remainder of plant proteins, oil and fibres continuing into the food chain. SAK is needed in 100% SAF blends to give the fuel the required aromatics for engine function.

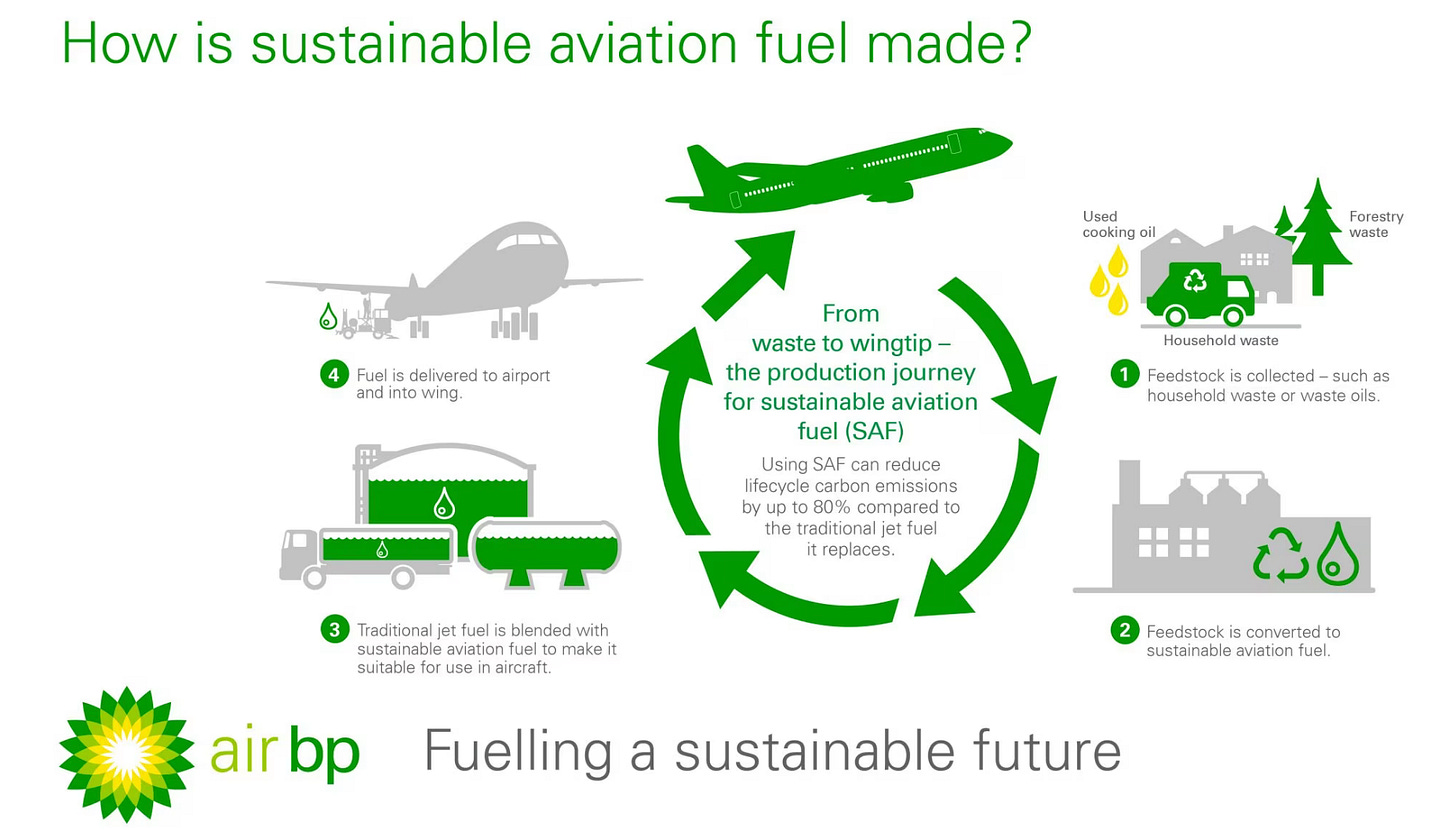

Hydroprocessed Esters and Fatty Acids are fats and oils that can come from many sources; the infographic lists forest wastes, but the Airbp site says, “Airbp’s SAF is currently made from used cooking oil and animal waste fat.” That’s known as FOG (fats, oils and grease) and is mostly beef tallow from slaughterhouses. There are competing uses for FOG, including food products, soap, and being turned into pet food and animal feed in the U.S. so there are serious supply limitations.

I don’t know how anyone could call beef tallow “sustainable” when we need to cut back on raising cows. It also doesn’t scale; we won’t be flying where and when we want on that.

The other fuel used in this flight was Virent’s synthesized aromatic kerosene (SAK), which is made from corn sugars in a process they call bioforming. This takes a lot of energy, so “Virent is targeting greater than 50% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions for SAK from a commercial project, with the potential to achieve net zero emissions using options such as renewable electricity, renewable natural gas and carbon capture and sequestration.” So it is not exactly sustainable, is it?

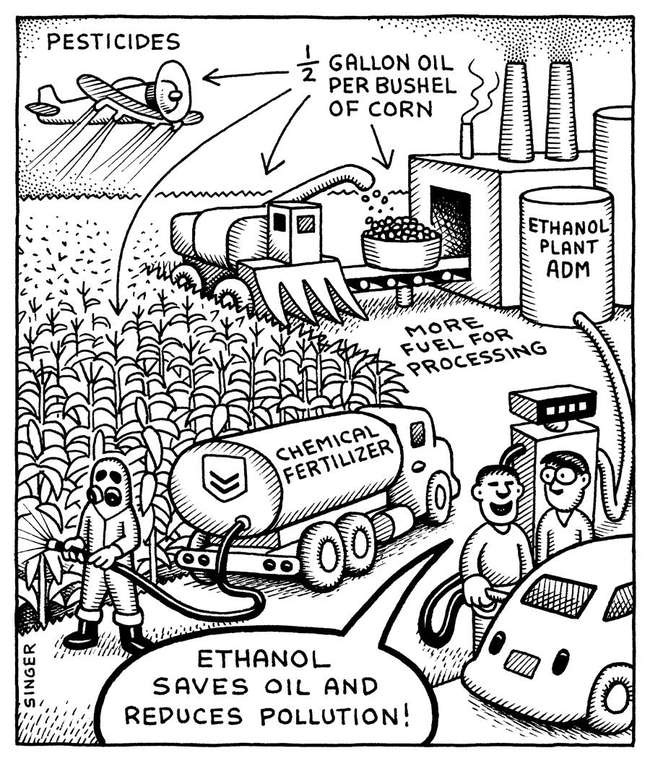

Then, of course, there is the growing of the corn, the source of the sugar for the Virent fuel. As Andy Singer notes, it takes a lot of energy, fertilizer and water to make stuff from corn. The American SAF industry plans on using ethanol. The New York Times recently wrote that “Carriers want to replace jet fuel with ethanol to fight global warming. That would require lots of corn, and lots of water.” President Biden recently said “Mark my words, the next 20 years, farmers are going to provide 95 percent of all the sustainable airline fuel.” The industry calls it “farm to fly.” But Dan Rutherford, aviation director at the International Council on Clean Transportation, said the UN has estimated that SAF from U.S. corn will reduce greenhouse gas emissions by just 10% The Times concurs:

Scientific studies have long questioned whether ethanol made from corn is in fact more climate-friendly than fossil fuels. Among other things, corn requires a huge amount of land, and it absorbs relatively little carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere as it grows. Planting, fertilizing, watering, harvesting, transporting and distilling corn into ethanol all require energy, most of which currently comes from fossil fuels.

40% of American corn is now turned into 15.8 billion gallons of ethanol, while 30% of soybeans go into making 2.1 billion gallons of biodiesel. and fed to cars, and the farmers hope that planes will take their place as cars go electric.

Meanwhile, Tim Searchinger of the World Resources Institute notes this takes a lot of land.

“The world needs to close a 70 percent “food gap” between crop calories available in 2006 and those needed in 2050. If crop-based biofuels were phased out by 2050, the food gap would shrink to 60 percent. But more ambitious biofuel targets—currently being pursued by large economies—could increase the gap to about 90 percent…For maize ethanol grown in Iowa, the figures are around 0.3 percent into biomass and 0.15 percent into ethanol. Such low conversion efficiencies explain why it takes a large amount of productive land to yield a small amount of bioenergy, and why bioenergy can so greatly increase global competition for land.”

I keep writing that there just aren't enough dead cows, and there is not enough land to keep us all up in the air, that we have to fly less and invest in more efficient forms of travel, like high-speed rail.

The aviation industry would have us plant corn from coast to coast and deforest Brazil for soybeans and Indonesia for palm oil to feed planes instead of people. In a world where climate change and war are causing shortages and price increases in all kinds of basic foodstuffs, I don't see how anyone could imagine that this is a good idea or how anyone could call fuel made from corn and cows “sustainable aviation fuel.” It isn’t, by any definition.

This is a bit of a smokescreen--pretending like aviation will soon be sustainable is a way of hiding just how unsustainable it is right now. Of course, this is an upper-middle-class strategy, as it is the wealthy who mainly do all the flying, such as Lloyd. All those folks like to fly without accounting or paying for their excess pollution, such as with valid offsets. Indeed, the science world doesn't spend much time figuring out the added warming from high-altitude emissions, which may be very significant. Those same scientists also love to fly frequently with no penalties for their pollution. It's a big blind spot, or an intentional looking away.

Some useful statistics to include in this subject would be: the energy cost of energy for making those sustainable fuels (i.e. the "energy returned for energy invested. For ethanol, this might be negative but there are some studies that have a 1.3:1 energy return. These studies rely on a lot of assumptions). Also, simply stating the cost of this fuel would show its problems. I've read it's 3-5x the cost of jet fuel, which would raise the cost of flying a similar amount.

But Lloyd is right in showing the system implications of trying to grow and process this type of fuel.

Thanks for sharing, what a story of greenwashing!