Cows burp a lot of methane. Does it cause climate change?

No, happy burgers are not back on the menu, but methane from cow burps may not be as bad as we thought.

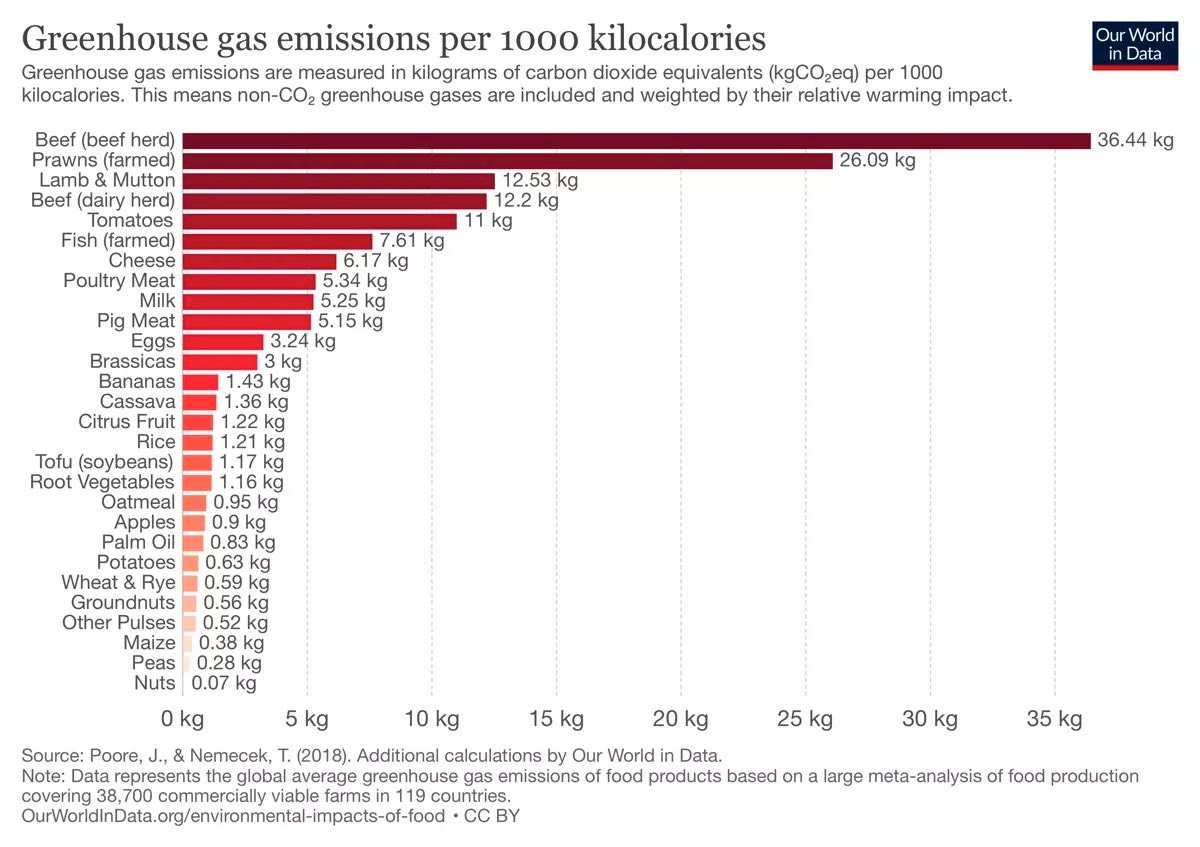

After a presentation of my book, Living the 1.5-degree lifestyle, to the Literary Table at Toronto's Arts and Letters Club, I did the rounds of tables when a gentleman confronted me about red meat, which I had said was a huge problem and had been cut out of my diet. I had shown my usual slide from Our World in Data, with beef at the top, demonstrably worse than any other food.

"Cows eat grass and burp methane," he said."but if they don't eat the grass, it dies and rots and emits methane. If they do eat the grass, then new grass grows and absorbs CO2. It's a natural cycle and isn't adding new methane to the atmosphere."

I acknowledged that I had heard this before but said the consensus was that cows are a significant source of greenhouse gases, not just because of the methane but because of the land use changes and the feed and the deforestation. Then another member piped in and said, "I'm from Ireland, and the cows eat grass from places where they have been eating for hundreds of years, and the land isn't good for anything else."

I slunk away and rode my bike home, thinking they had a point. Or was this greenwashing, like the people who say burning forests of wood for electricity as they do in the UK is carbon neutral because it is "biogenic" and "fast carbon," not fossil carbon?

But a cow munching grass, burping methane and pooping fertilizer to make new grass is really fast carbon.

I always say carbon is carbon and methane is methane; the atmosphere doesn't care where it’s from. It’s known that methane is a potent greenhouse gas and that meat consumption is responsible for 40% of methane emissions due to enteric fermentation. (the rest is mostly leaking fossil/natural gas). Some go so far as to say that addressing methane from meat is the fastest way to reverse climate change. Are we wrong?

An internet search turned up dozens of beef industry websites and American right-wing websites denying that "cows are the new coal." But even my beloved Quirks and Quarks from the CBC answered the question: do cows produce more methane than rotting grass? They spoke to Christine Baes, a professor at the University of Guelph.

"She said that it's important to note that methane is not released by the cows themselves, but the bacteria in their gut. Similar bacteria also exist in the environment and produce methane in wetlands, rice fields and landfills. The actual amount of methane released from a single blade of grass wouldn't change if it was just left to decompose, or if it was eaten by a cow and then digested by the bacteria in their gut. The only difference is that the methane would be released more quickly by a cow or other ruminants (animals that acquire nutrients from plant-based foods with the help of microorganisms)."

UPDATE: See bottom of the post; this is not entirely accurate.

So have I been denying myself the pleasure of a juicy steak or a fat hamburger for nothing?

Not quite. Hannah Richie of Our World in Data looked at this, acknowledging that methane is a short-lived gas and doesn't stay in the atmosphere for very long compared to CO2. She did not discuss whether we should discount it because it was biogenic or part of a short natural cycle but did the math excluding emissions from methane. Beef is half as bad without methane but still worse than everything else.

"The average footprint of beef, excluding methane, is 36 kilograms of CO2eq per kilogram. This is still nearly four times the mean footprint of chicken. Or 10 to 100 times the footprint of most plant-based foods. Where do the non-methane emissions from cattle and lamb come from? For most producers the key emissions sources are due land use changes; the conversion of peat soils to agriculture; the land required to grow animal feed; the pasture management (including liming, fertilizing, and irrigation); and the emissions from slaughter waste."

My usual table at the top lists the carbon emissions per 1000 calories of food; the one excluding methane is per kilogram of food, which is silly; eating a kilogram of steak is very different than eating a kilogram of tofu.

So Richie did another graph comparing the carbon footprint based on eating a hundred grams of protein, which you can get from either beef or tofu. And it becomes apparent that beef should still be off the menu, given that it is still over four times as bad as chicken and thirteen times as bad as tofu.

Other sites confirm that the bulk of emissions from livestock farming come from feed production, processing, transport and storage of manure, and there are so many cows that it adds up to a big chunk of the world's emissions, even without methane.

Many reject red meat without considering carbon; my daughter rejects it for ethical reasons, and there are land use, waste and health issues that should concern us.

So I am not rushing out to Happy Burger for dinner; there are still many reasons to eat red meat in moderation or avoid it altogether. It still has a massive carbon footprint. But I will admit that from a greenhouse gas perspective, the methane skeptics do have a point.

UPDATE: A reader notes that grass dying in the field differs from grass digested in a cow. “You've not been wrong. Cows produce methane because the grass (or other feed) is digested in their rumens via enteric digestion, an anaerobic process ("without oxygen") that produces methane. If the grass wasn't eaten, it would mostly compost naturally in the presence of oxygen, hence producing carbon dioxide, a much less potent greenhouse gas than methane.” Others like Umbra at Grist concur.

“Even if we did just let all the world’s cattle feed rot in place, methane wouldn’t rise from our fields like so many stinky cartoon lines. That’s because methane typically requires anaerobic (oxygen-free) conditions in order to form, like the environment you’d find underwater in, say, a bog or marsh. When oxygen is available — as it is in an open field — the bacteria decomposing the plants will instead emit carbon dioxide, water, nutrients, and carbon compounds (which help to enrich the soil for new plants, by the way).”

To expand on the "grass is oxidized" idea, even in later decomposition stages when methane _is_ produced the soil contain methanotrophic bacteria that oxidize the methane so it never reaches the atmosphere. So there are no detectable methane emissions, as shown in the paper below.

With cattle emissions the methane is emitted directly to the atmosphere.

From Hartmann, "A study of soil methane sink regulation in two grasslands

exposed to drought and N fertilization", 2010:

"The grasslands investigated continuously acted as net

sinks for atmospheric CH 4. We never detected CH 4

emissions from soils, even when soils were water-

logged after heavy rain or snow melt."

Your comments about how the grass and field decomposition would be less is not well established

See attached research paper done in the Netherlands

https://edepot.wur.nl/201574