Confessions of a Climate Hypocrite: Learning to Live with Nuance

Sami Grover contributes his thoughts

Sami Grover is a writer and a friend who has also written a just-published book which I have been afraid to read, worried that it would change the way I think about my own. I asked him to do a guest post here in the hopes it might give me the courage to open his book.

The world of online environmentalism doesn’t do nuance very well. You’ve probably seen the warring camps online. On the one hand, we’re told that any call for climate action is invalid, unless it’s coming from an eco-saint:

“You can’t be an environmentalist if you fly [eat meat/use a computer/drive a car/wear shoes]!”

On the other hand, folks claim that we have no personal agency:

“100 companies are responsible for 70% of emissions. Only systemic change matters!”

The real truth is somewhere in between.

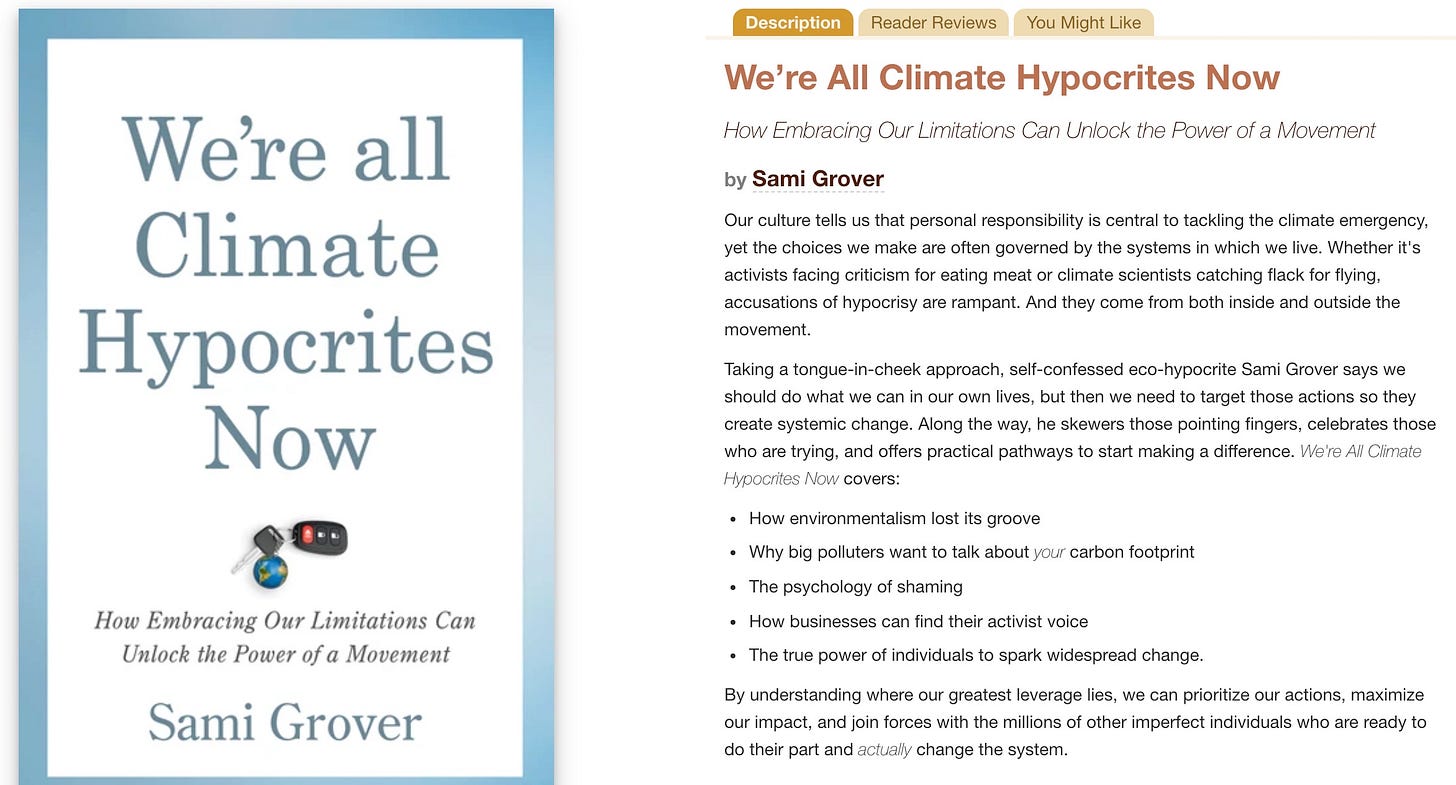

I’ve spent the last year writing a book called We’re All Climate Hypocrites Now: How Embracing Our Limitations Can Unlock the Power of a Movement. It was originally conceived out of frustration at the idea that if we could all just compost enough, or not fly as much, then we could bring this crisis under control. Yet the more I dug into the topic, the more I realized it was a strange argument for me—in particular—to be making.

I actually go to significant lengths to try and limit my own carbon footprint. I drive an old, used, and ugly electric car, for example. I limit my consumption of red meat. And I have been known to dig through the household trash to find cardboard that really should be headed for the compost heap.

Yet these efforts have only gotten me so far. Despite my vegetable growing and tree planting, my e-biking and insulating, the last time I checked, my carbon footprint was only around 25% lower than the American average. Exactly why my progress has been limited will depend upon which aspect of my lifestyle you choose to scrutinize:

· My adopted home state of North Carolina remains a car-centric, transit-unfriendly environment to move around in

· The Republican-led state legislature continues to stymie efforts toward 100% renewables

· And as a Brit living abroad, my family obligations and yearning for home mean that I fly about once a year, both to visit my family and to drink proper beer

As the examples above suggest, some emissions are hard—perhaps even impossible—for me as an individual to avoid. But I’d be lying to myself if I said that they are all outside of my control. I still indulge in steak occasionally. I buy things online that I really don’t need. And I’ve been known to crank up the AC when North Carolina gets too hot for an Englishman.

When Lloyd first told me about his own book—Living the 1.5 Degree Lifestyle—I confess I was a little surprised. He knows better than most how corporations have used calls for ‘individual responsibility’ to avoid facing consequences for the problems they create—most notably in the form of pro-recycling and anti-littering campaigns in the 70s and 80s. Yet as Lloyd has also forcefully argued, he is old enough to remember how consumer boycotts helped bring down the Apartheid regime in South Africa.

“We need to stop buying what they are selling,” says Lloyd. And here, I think, we are in agreement.

When I first started researching my book, I used an analogy that I thought was rather clever: The transatlantic slave trade didn’t end because people stopped eating sugar. Yet it turns out that this is only half true. In fact, consumer boycotts were a central strategy of abolitionists. At one point, some 400,000 people in Britain alone were said to be boycotting slave-grown sugar.

The crucial point, however, ws that the abolitionists weren’t suggesting that nationwide abstinence from sugar was the ultimate solution to ending slavery. Instead, they were tactically pulling the lever of abstinence with a specific end goal in mind. And they were doing so as part of a broader set of strategies.

There’s a lesson to be learned for the climate movement. We need to start thinking about behavior change as an act of mass mobilization:

· That means focusing on those actions that really make an impact.

· It means avoiding the distractions of what George Monbiot has called “Micro Consumerist Bollocks” (MCBs for short).

· And it means building strategic and inclusive movements where non-flyers work in concert with reluctant flyers, where vegans join hands with the “reducetarians,” and where bicyclists accept and welcome the help of those not yet ready to give up the minivan.

The 1.5 degree lifestyle approach can be immensely valuable in this regard. Not only does it directly reduce demand for fossil fuels, but as Lloyd told me when I interviewed him for my book, it also helps to illustrate where the system is holding us back:

What I’ve learned is that if you’re a rich boomer who bought a house in a nice part of town and you’re close enough to bicycle anywhere and you work from home, then it’s actually pretty easy to get close to this type of lifestyle. As soon as you’re in a position that you have to commute by car, then all that goes out the window. It was easy for me to change because I had the big things already built in. If someone who lived five miles north of me wanted to do this, they have to make much tougher choices.

The only hesitation I have is that living the 1.5 degree lifestyle is just one approach among many. And while it can and should help inform how we bring our emissions down, I believe it is doomed to fail if it becomes the litmus test for how every climate activist should act, or an exercise in unattainable gatekeeping that locks people out of the movement.

Ultimately, we need to remember the only carbon footprint that matters: that of society as a whole. The degree (pun intended) to which behavior change can help in this regard will depend entirely on if and how it helps bring others along for the (sorry!) ride.