Bonus: Who will save our digital memories?

From my archives, a look at what happens when we don't thow our photos in a shoebox.

I have been reading how writers at Vice are madly backing up all their posts before the site shuts down, worried that they might lose them all. This happened to me, so I diligently backed up all my posts for MNN.com. I was not fast enough to get all my Treehugger posts before they started “cleaning up” the site, but signed up for Authory to scan the net, looking for my content. This is a problem everyone faces with their digital cameras and iphone photos. Who will save them? I wrote about this for both MNN and Treehugger and of course, both posts have been removed. From my archives, November 23, 2015.

Who will save our digital memories?

We may well have a digital Storage Wars where they are thrown out onto the curb.

In 2007, TreeHugger became part of Discovery Communications and I started writing for their new website, Planet Green. As the Great Recession kicked in, I concentrated on writing about frugal green living, and over the next four years wrote about 1,000 posts; my wife, Kelly Rossiter, wrote a post a day about food, frugal eating, how to start a pantry; her stuff was really wonderful. It would all be relevant today on MNN, where TreeHugger landed three years ago, and I would love to publish it there, but it’s gone — lost when they pulled the plug on the Planet Green network. Kelly is still upset over what was lost.

So much of what is written today — in fact anything that's published on the Internet — might well suffer the same fate. If a company as big and successful as Discovery Communications doesn’t see the value in paying for a backup for archival reasons, who would?

Over at Metropolis magazine, the wonderful editor Susan Szenasy is dealing with this issue as they move to a new office. She writes in her editorial on Preserving Paper,about the fate of non-digital archives:

Prior to our move, massive amounts of paper from files, as well as magazines and books, went to be recycled. This industrial process was an efficient one. Large plastic bins on wheels were filled with all manner of papers, including the posters I once fondly taped to my door and wall. A truck parked downstairs ground up the content of a dozen bins in a matter of minutes. All that we once thought important, all that recorded knowledge, is gone — trash.

I know this feeling well. After I closed my architectural practice, I stored all of my drawings (most done by hand back then, or printed out if digital) in an expensive locker for 15 years, thinking they had value to clients, to archives, to history. Tired of paying $150 a month for storage, I called the shredder people and the drawings were all turned into mylar fluff, gone in about 20 minutes, 10 years of my life as an architect. (The buildings themselves are not far behind in the real estate frenzy that is Toronto.)

Susan asks: “All this trash makes me wonder — in our mad dash into the digital world, what happens to our nondigital history?” I worry more about our digital history. I have almost no photos of my kids in their teenage years. Being an early adopter, I took all my photos at 640 x 480 on the first Olympus digital camera, saved the digital photos on a CD that I cannot find and even if I could, I wouldn't be able to play it on my current computers. The few printouts I did have are all fading to nothingness, like this one of my daughter, about the only photo I have of her from this era.

I also was one of the earliest adopters of computer-aided design, designing buildings on 8 Mz IBM AT clones and storing data on 5-1/4 floppy disks. I once tried to retrieve a drawing that was done in about 1989. What a task: I had to find a computer with the big drive, go through about 12 upgrades of the CAD software, and the results I got were so distorted I could only save them as a sort of art project. Susan wonders “Who will invest in archiving the less exciting but still essential physical record of the work it took to build a solid foundation for our professional practices?” I have no idea; I know mine is lost, both paper and digital.

After thinking about this issue, I've taken to doing all my writing of posts for MNN and TreeHugger offline in a word processor and saving them for posterity, but of course I do this on the iCloud, that big storage locker in the sky. I suppose that some day, I won’t make the monthly payment, my kids won’t know the password or maybe not care about it, and there will be a digital version of "Storage Wars" where they try and sell the contents of my locker and if that doesn’t work, dump it out into the virtual street.

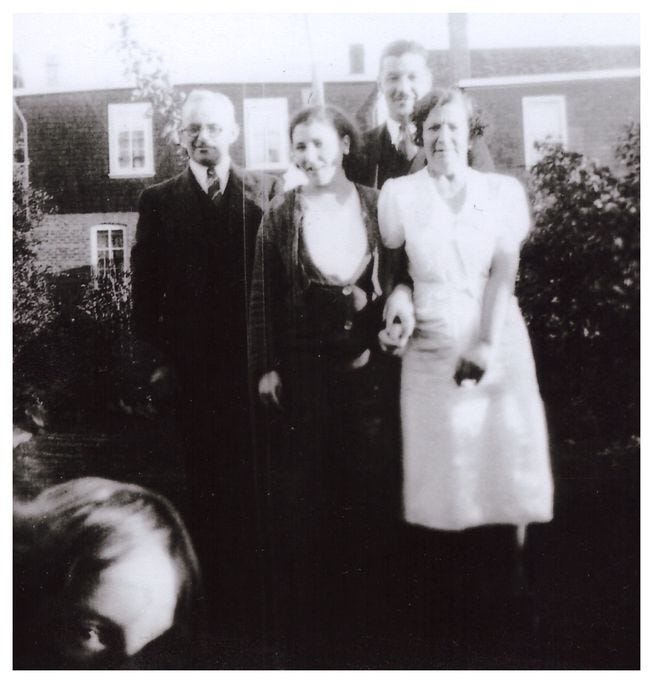

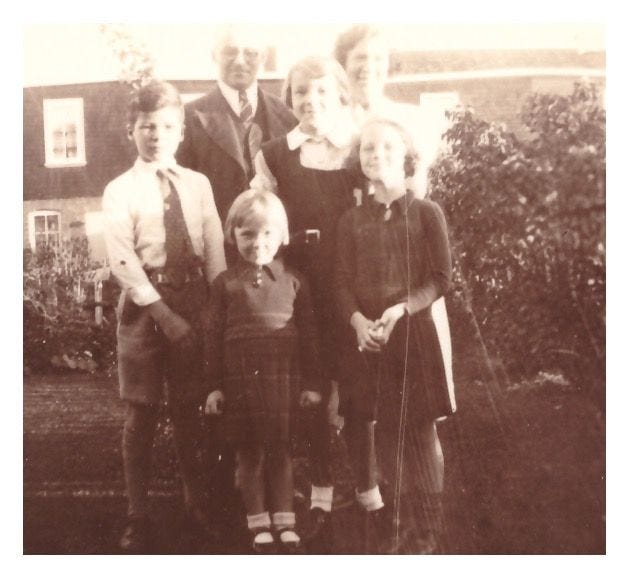

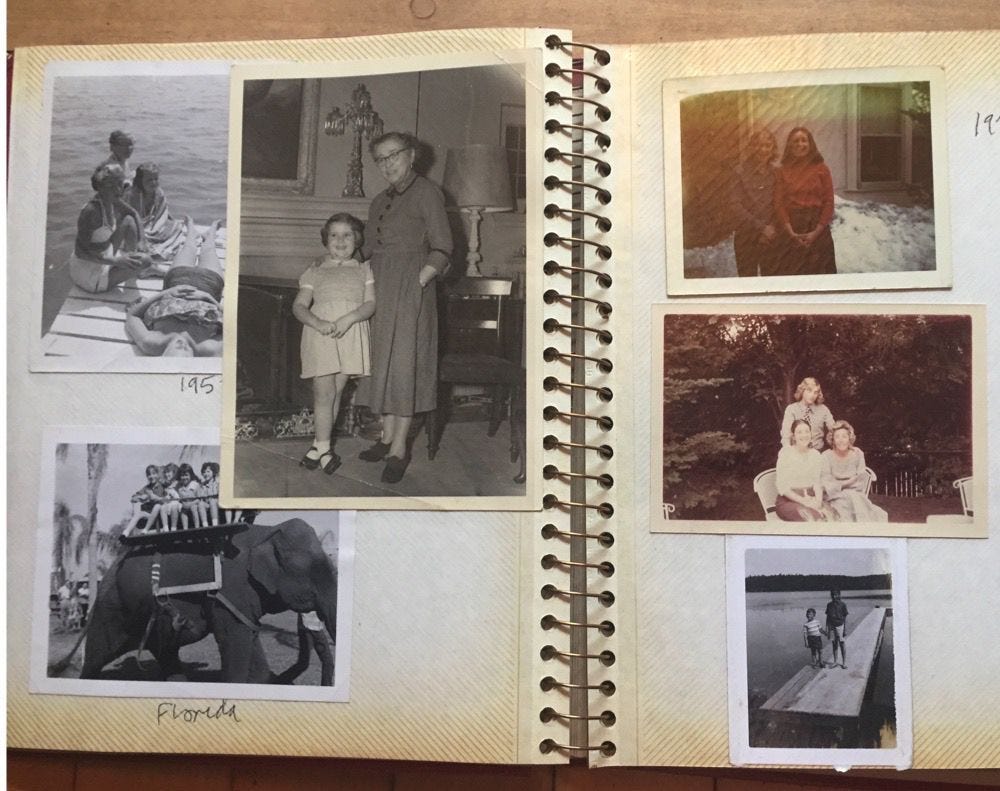

After Kelly’s mother died, she found a pile of photo albums full of family photos of distant cousins. She had no idea why her mother would have had them, but she called up her second cousins and arranged to give them the albums. The 90-year-old matriarch of the family had never seen these photos, everybody cried as she described who everyone was in this treasure trove of family history that somehow ended up in my mother-in-law’s basement. However, they were found, they were returned to their family, and they are now treasured. What will happen if Yahoo! turns off Flickr or Google gives up on Photo? Will we have any record of our families, our history, our work, our accomplishments?

I cannot help but wonder whether historians of the 22nd century won’t have a very big hole of missing information starting around the beginning of the 21st.

A few years later for Treehugger I wrote about this again, expanding it a bit to include storage services that are now available. Some links to them have already failed. From my archives, August 2017.

How Will We Bequeath Our Digital Memories?

After I posted "Mom may be gone, but what about all her stuff?" a reader asked about photographs, particularly in this digital age. Frank wrote that “this issue challenges me. How many people have properly stored their digital images let alone labelled them so they have meaning for future generations?”

It is an issue that has challenged me too. Being an early adopter, I got an early Olympus digital camera that took only 20 small 640 x 480 photos which I printed out and stuck on the wall of our cabin; 20 years later, the old Polaroids are perfect, the conventional photos are perfect, and the digital prints are faded and almost gone. I thought I had burned them onto CDs but I cannot find them; there is now probably close to a decade of my kids growing up that is gone.

My mom used to take family photos and throw them into all her lacquer boxes; I worried that it would take forever to go through them all. Then I found that my sister did that with mom over five years. She mounted and labelled them all and threw the rest away, so now we have two carefully curated albums of not very many photos — because film and printing was expensive, and people didn’t take that many.

Photographer Ming Thein writes about the few photos he has of his grandparents, and makes a good point about how it is really an issue of quality over quantity.

Those ten images of my grandma’s that survived probably did so precisely because there were only ten or maybe eleven to begin with; scarcity attached value, and value precipitated a reasonable amount of care....

I often think that our children or grandchildren won’t have much interest at all, being surrounded by thousands of images on Instagram and Facebook and they are totally ephemeral. I have wondered who will save our digital memories? before on MNN, but really didn’t know what to do. Because as Thein notes, unlike the era of the old black and white prints, we now have a technological problem.

It is said that the more advanced a civilisation, the fewer the number of clues it leaves to its passing and the details of its time; if you carve your art into stone, it’ll probably weather quite well. But if your art is on a digital medium that requires specialized precision equipment to read and decode, chances are it’ll never be seen again once the original creator loses interest – it’s just too much effort for anybody without some degree of self-interest in it.

I have negatives from photos that I took when I was 13 years old and started playing in darkrooms, and that can still be printed. But digital storage media keep changing; even if I found my old CDs I no longer have a computer with a CD drive, and CDs don’t last that long anyway. I store everything now on the iCloud Photo Library which I love; I can find people by name, find places by location type in “bike” and get every photo with a bike in it. Google Photo is apparently even more sophisticated. But Apple storage isn’t free, my family doesn’t have access to them all, and they could all disappear when I do and nobody pays the data bill. There are also many people who are not comfortable keeping their photos on the cloud because of privacy concerns. (That’s why I don’t use Google Photo; as Tim Cook of Apple notes, “when an online service is free, you’re not the customer. You’re the product.”)

Professional photo organizer Cindy Browning (yes, there is such a thing, there is even an organization, the Association of Personal Photo Organizers! Who knew?) tells the CBC that people should have a “digital hub” — one place that they make sure all their photos go, where you download camera and phone photos, whether in their computer or on a separate hard drive. That should be backed up in at least two other places, one of which is kept somewhere else in case of fire or flood. (I let Apple’s iCloud Photo Library be my hub but really should have a backup or alternate to that.)

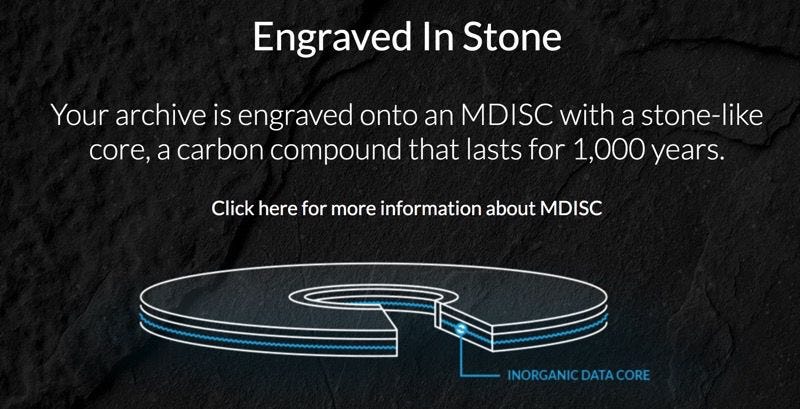

There are other, more permanent solutions; Yours.co takes your photos and burns them onto an MDISC, a special DVD with a “rock-like” core that they claim will hold your data for a thousand years. But that assumes that you will have a DVD drive in a thousand years.

Another service worth looking at is Forever. It’s a cloud-based service that you can pay for by the year, but it gets really interesting when you prepay a chunk of money for Forever service: $299 for 10 GB of storage, about 2,500 photos, or $499 for 100GB, about 25,000 photos. They promise to keep your photos for 100 years beyond your death.

They take the majority of the money and invest it in the “ForeverTM Guarantee Fund (PDF), the world's largest permanent investment fund dedicated to content preservation.” I have read the entire investment policy and it seems legit, but like any investment, there are no guarantees, and who knows if there will be anyone around to keep the site going, but they are certainly trying to give as much comfort and security as possible.

They also have a strong privacy policy (although not nearly as strong as Apple’s when it comes to sharing information with the government and legal authorities) and will upgrade formats of photos as necessary.

But in the end, none of this works if we have war, rapture, meteor strikes or any of the other disasters that might wipe out the internet or the grid. I keep thinking that we should perhaps print out the best dozen photos we have on archival paper, frame a set of them and pack some small prints in our bug-out bag for when we have to hit "The Road." And I suspect that if I picked very carefully among my 23,000 digital pictures, a dozen is all I would really need to define a life.

I cracked up the other day watching a clip on YouTube from one of The Next Generation Star Trek movies and I got to hear Geordie repeat his variation of the Spock mantra, “Captain, it appears to be a primitive data storage device” as he manipulated a salt shaker or some other exotically shaped article tracked down by Props!

Great stuff, Lloyd.