Between the crowds and the carbon, we should reconsider the "museum without walls"

Will 3D headsets like the Apple Vision Pro change the way we look at art?

Kelly and I were complaining about people who go to art galleries and see everything through their smartphones. "I don't understand why people take pictures; there are thousands of better ones online," she said. "just absorb the power of the art." I wondered if we wouldn't be better off just looking at the photographs, and thought about what will happen in the new world of the Apple Vision Pro headsets. Couldn't we now see the museum and the art in high-quality virtual reality? My wife looked at me blankly; she is no fan of technology or Apple, but hear me out. This may be our future.

When I visited the Belvedere Palace in Vienna a few years ago, so many people wanted selfies with Gustav Klimt's painting, the Kiss, that the museum set up a "selfie point" where visitors could take a picture of themselves with a reproduction of the artwork. Everybody seemed just fine with the idea of going all the way to Vienna to take a photo of a photo. I wondered if we wouldn't all be better off looking at high-resolution images and saving the airfare.

It's becoming impossible to see famous art anyway. Shortly after I returned from Vienna, Art critic Jason Fargo complained about the Mona Lisa.

"The Louvre is being held hostage by the Kim Kardashian of 16th-century Italian portraiture: the handsome but only derately interesting Lisa Gherardini, better known (after her husband) as La Gioconda, whose renown so eclipses her importance that no one can even remember how she got famous in the first place."

You can't get close to it, you can't take any time with it, and it has been voted the world's most disappointing tourist attraction. If the experience is so bad, why not consider alternatives? I know this sounds stupid coming from a guy who is getting on a plane to Paris tomorrow, but I won't be going to see the Mona Lisa. As Yogi Berra famously said about a restaurant in St. Louis, "Nobody goes there anymore, it's too crowded." When you get close enough to see it, you are looking through half an inch of glass protecting it from soup-throwing Just Stop Oil activists.

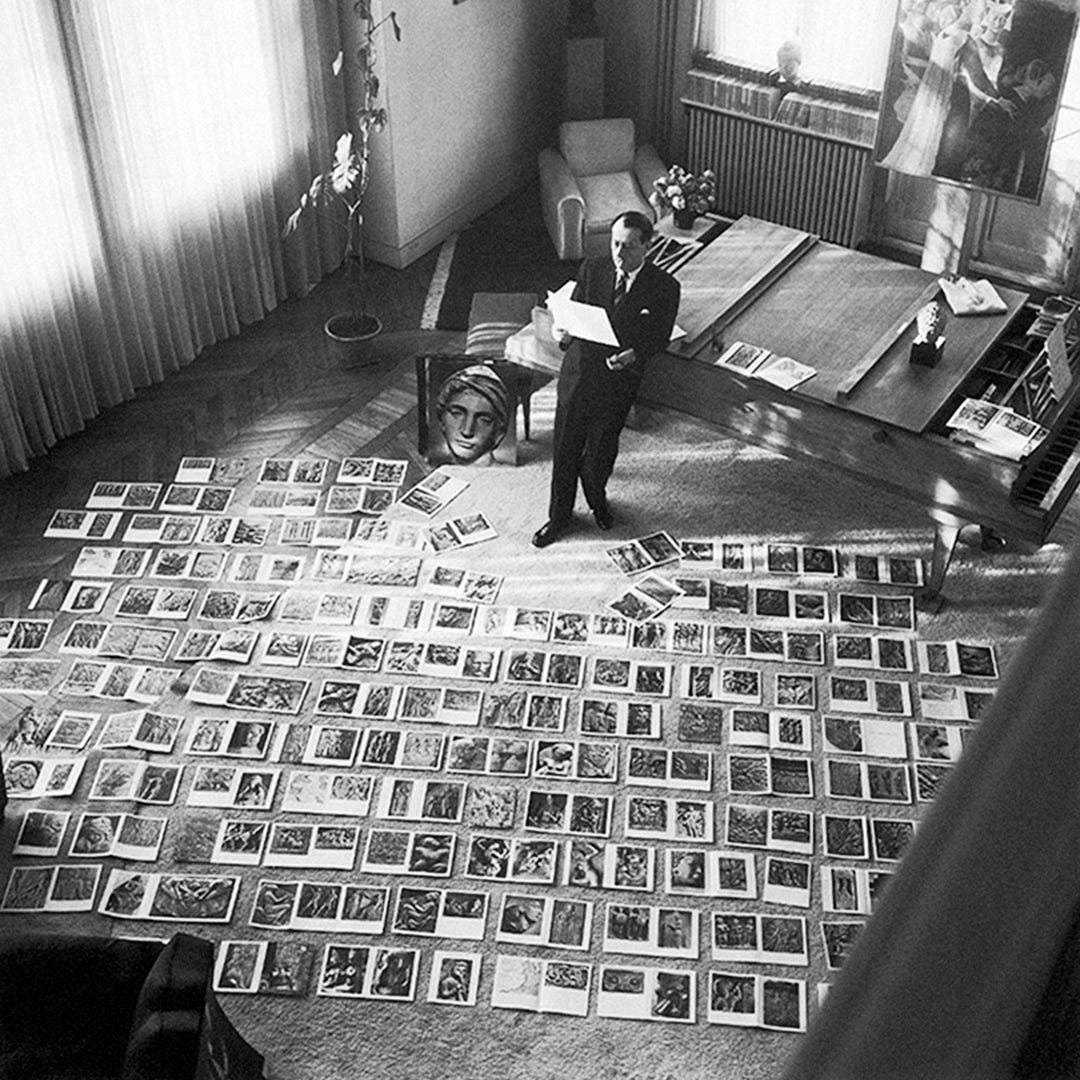

My discussion with Kelly made me think of André Malraux and his vision in 1952 of "le Musee imaginaire" or Museum without Walls. He suggested that the traditional museum was no longer relevant, as photography had become so good that it made art accessible to all and might even provide a richer experience.

"Great art, he wrote, made accessible to all through reproductions in books, is liberated from the time, place, and history in which they are usually confined by museum categories. Removed from historical context, they can be rearranged in the mind according to aesthetic or philosophical qualities."

He worried that there was too much art:

"Given that the breadth and diversity of today's world of art far surpasses the capacities of any single art museum, or even two or three, and that many of the objects are in any case not moveable, the musée imaginaire is our imaginary collection of all the works, both inside and outside art museums, that we today regard as important works of art."

Today, the problem is too many people, most carrying cameras and some carrying soup.

Malraux only had photographs. Malraux scholar Derek Allan of Australian National University thinks Malraux would have loved computers, writing in 2010:

"What would Malraux have thought about digital reproduction and the greatly improved access to images made possible by the Internet? We we can only conjecture, of course, but personally I haven't the slightest doubt that he would have welcomed both with enthusiasm. If photography was, in his words, visual art's printing press, then the advances we've now seen in digital technology would, in his eyes, have represented a series of brilliant new opportunities for this "printing press ."The musée imaginaire, he would have thought, could now not only be a museum in the mind but one that each of us could increasingly bring to life at will on a computer screen."

But a two-dimensional photograph or high-resolution monitor can't reproduce the most powerful experience viewing art that I ever had, at the Galleria Borghese in Rome, viewing The Rape of Proserpina, carved by a 23-year-old Gian Lorenzo Bernini. The hand, the thigh, everything was just so real it was surreal. You have to walk around and see it from all angles; you have to get up close and see the flesh turned into marble.

I wonder if the Apple Vision Pro will be the new Museum without Walls. I haven’t tried it yet, but the reviews of "Immersive Video, a new format that delivers a 3D experience via 8K recordings with a 180-degree field of view" are all WOW. The Galleria Borghese gets pretty crowded now; I wonder if walking around the Bernini with a headset from the comfort of my sofa might not have its advantages, not including the carbon savings.

It sounds a bit like the "feelies" described by Aldous Huxley in Brave New World and later by Mike Ferren, where we get wired up and view the world through 3D goggles and a stimulator suit. But between the crowds and the carbon, someday this may be the only way to fly.

I can see it as an option but would not want this to become the way to interact with art especially at the risk of leaving one more real experience as a private domain of the privileged class. The first day of work in Washington DC after the 9/11 attack saw me heading for the FEMA HQ near the Washington Mall to work a shift as the State Department rep dealing with the international side of the attacks. I was very glad to have time to pop into the National Gallery and spend some time with the French Impressionists before reporting for my shift.

Another really thoughtful article, Lloyd; but as a wall-painting conservator, I think I should draw attention to some missing dimensions. Possibly things that virtual reality will indeed pick up, eventually; and yet and yet... there's such a lot going on with how we perceive the world around us, and not least the painted image. Photos only give you a thin slice of that reality, a bit like 'Flatland'.

This obsession of visitor for taking photographs of famous works was something that bugged me and a few of the others lucky enough to score tickets for last year's wonderful Vermeer exhibition at the Rijksmuseum. So many people took no time at all, not even a second, to look closely at the painting itself, although they'd travelled so far to see it. If they had, it would have helped them realise there was more there in the paintings that the eye could easily see, but the photos can't capture. Some of that is due to metamerism - the CCDs are tuned to be sensitive to particular wavelengths, which are different to those the eye can pick up - and even more is due to texture. You can see that in your first image: the photo reproduction actually looks nothing like the painting, because it's mirror flat.

There is also the special thing that comes from the movement of light - but of course you'll miss that in a gallery anyway!

But finally, there's the odd truth that the pictures in galleries are actually imitating photography: unlike most wall paintings, easel paintings are retouched to an inch of their lives, and then all too frequently finished with matt synthetic varnishes that are very different to the dense shiny oil-based varnishes of the past. The result is something that can be easily photographed, but is very far from what the artist actually had in mind. A bit of name-and-shame here (it's a long time ago): this was strikingly shown a couple of decades back in London, when the Dublin Caravaggio, on its way to its final home after a very sensitive restoration in Italy, was shown alongside the Caravaggio paintings in the National Gallery's collection. These had been treated in the house cleaning and restoration style, and then given a matt Paraloid varnish. They looked just FLAT, in every sense of the term. I won't go into what it is about choice of cleaning methodology or of varnish that produces these effects, but even at the time it was clear to us that the NG approach was driven by the wish to allow people to see the image clearly from every angle. Which also permits photography, of course...

That said, I'd draw everyone's attention to the wonderful resource we now have, with so many great libraries and collections providing digitised images of their medieval manuscripts for free on line. You can even zoom in and examine details. But do be aware that the originals were invariably teeny tiny, and were painted on cockled vellum rather than flat paper. And can a photograph of gilding ever give us more than a faint idea of the wonderful effect it produces in reality, on the moving eye?