As our cities get flooded or boiled, it's time to get serious about resilient design

Houston still doesn't have its lights on, and Toronto is under water. We can't keep doing this.

I read this morning in the Financial Times that a week after being hit by the relatively mild Hurricane Beryl, almost a quarter of a million homes still don’t have electricity in the 100°F heat.

“This is a city that is commonly in hurricane path . . . and we’ve seen some really big ones. But this was not a major hurricane. This was a category one. And to have a million people out of power for over a week? It’s a complete lack of preparation.” There were almost a quarter of a million customers, or households, still without power last night, according to poweroutage.us, which analysts said likely equated to more than a million people as a heatwave has pushed temperatures close to 100F (37C).”

Meanwhile in Toronto where I live, streets, subways, train stations and basements are flooded, and the Provincial Government continues with its plans to build a $650 million underground parking garage on the waterfront to service a private spa, and to build highways across the greenbelt that currently soaks up rainwater. Governments seem to be oblivous to the problem; back in Texas, the governor blames the power company, but the FT dares to mention climate change.

“The failure of power companies to provide power to their customers is completely unacceptable,” said Texas Governor Greg Abbott at a press conference on Sunday… In a world where climate change is driving a growing number of extreme weather events, the ability of electric grids and utilities to cope is increasingly coming under the microscope.

Coincidentally, I was writing about thermal comfort and looking for an article by Professor Susan Roaf about adapting to hot climates. In an article for BDonline she references Houston, where hundreds died from cold in an ice storm in 2021. She notes:

“For a start many architects design buildings with no, few or barely opening windows. Secondly, fashion dictates that homes have large open-plan living areas with kitchen, dining room and seating areas in large, expensive to heat and easy to overheat spaces. There are no thermal refuges anymore, no snugs or cool rooms.”

In the article I was looking for, Comfort, Culture and Climate Change, Roaf explains how we became dependent on air conditioning, but also lays out a road map for reducing our need for it, as they do in Houston right now.

While buildings in many regions of the world may continue to need to be air- conditioned in the hottest times of day or year there are many good reasons why air- conditioning should now be considered to be the cooling strategy of last resort. Not least of these is because of the likelihood in the final decades of the fossil fuel age of regular failure of large electricity grid systems at times of extreme weather.

She has many recommendations, including a few I have picked here:

Shallow plans for better daylight and natural ventilation

Opening windows of a sensible size to avoid over-heating and allow for natural ventilation.

Adaptive skins with elements such as shades, awnings, blinds and shutters designed to maximize the potential to protect buildings from wind and sun.

High levels of thermal mass to stabilize internal temperatures in heat waves or cold snaps and to store free renewable energy. The inherent response time of a building to external temperature fluctuations determines the ability of that building to ride a heat wave with acceptable indoor temperatures.

Robust buildings that are not vulnerable to catastrophic failure and buildings that are not totally dependant on grid electricity to remain functional and occupied.

Roaf concludes that we need a new 21st century building type, “adapting the best of the passive design wisdom from the 19th century,” but also integrating everything we have learned about ultra-efficient technologies and “embedded forms of renewable energy to create a New Vernacular for the 21st century at the heart of which will have to be a new approach to the understanding of thermal comfort, an adaptive approach.”

There are many who disagree with Susan Roaf, especially with her attitude toward Passivhaus (“Building regulations are stuck in the 1990s, still dwelling on issues like air leakage, cold bridging and U-values (the old Fabric First mantra)” and her love of thermal mass, which I have discounted many times as I thought it was only useful when there are large diurnal swings, as found in many of the hot countries where Roaf has worked.

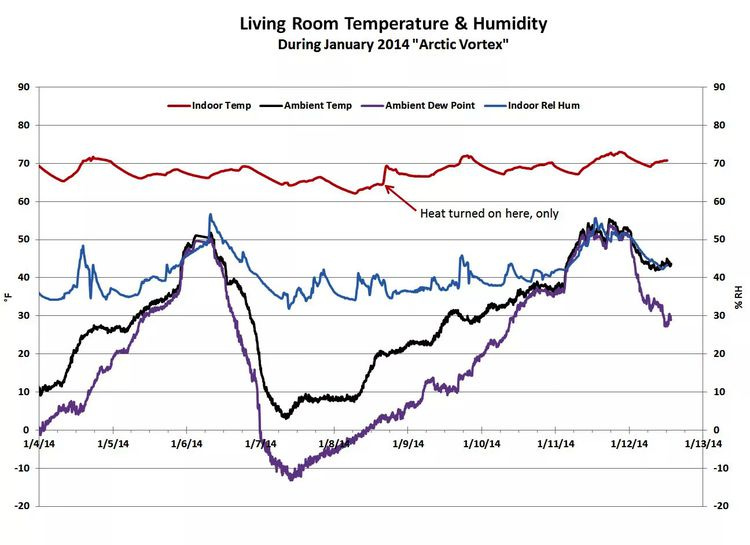

I have often made the case that those “fabric first” measures give you resilience, noting that just like Roaf’s thermal mass, Passivhaus can work as a “thermal battery”, excluding or retaining heat when electricity is lost due to weather or lack of renewable energy. I wrote an ode to Passivhaus after a cold snap:

"Every building should have a proven level of insulation, air tightness, and window quality so that people are comfortable in all kinds of weather, even when the power goes out. This is because our houses have become lifeboats, and leaks may well be fatal."

But whether I agree with all of Roaf’s arguments or not, the conclusion is the same. Looking at Houston as an example, as it fails to deal with ice storms or hurricanes, it becomes clear that our homes need much more resilience and self-sufficiency, with less dependence on centralized resources. Last words to Roaf from another BD online article:

“We need urgently to refocus on investment in upgrading our building stock to save future lives, not least because buildings are our first line of defence against ever more extreme weather events – not machines and not the grid.”

Have a listen to Susan on the Zero Ambitions Podcast where she discusses “the way we approach managing thermal comfort, problems with architectural education, the flaws in solely thinking about decarbonisation of the grid as a panacea, problems with designing buildings have an over-reliance on technology”

Reviewing Lloyd's post and previous comments, there must be a variety of 'correct' answers for different locations.

Underground electricity and other wires (cable, fibre-optics) may not be a solution in seriously flood-prone areas; overhead very high voltage electricity on steel transmission towers is probably not currently economically feasible with underground ducts, but reinforcing the towers and wires against wind and ice should be an obvious temporary solution. In England, a high-voltage transmission line has been placed in a disused railway tunnel rather than over the Pennine mountains.

Understreet conduits containing 'everything' might be OK in some areas, but not in low-lying and flood-prone areas. Just don't mix fossil gas with electricity in the same enclosed space...

No-one so far mentioned above-ground conduits. Not pretty, but there are examples in Inuvik, NWT where the normally buried utilities are elevated at the back of the buildings, which are also elevated, originally to prevent thawing the permafrost. Check Google Earth and Streetview for examples.

Cost has been mentioned several times as a reason for not doing 'better'. The true cost of (for example) undergrounding electrical cables should also include the advantage or 'non-cost' of not having to replace downed cables and the losses incurred by the utility's customers, and the environmental and aesthetic 'non-cost' of a more attractive environment (check the absence of overhead wires in Inuvik - the wires may be in the utilidor).

It should go without saying, but I'll say it anyway. The world is changing; do not rebuild, or build, in flood-prone areas!

Just a quick comment for you, Lloyd.

With your examples of large cities, did you ever entertain the thought(s) that perhaps the problem IS the cities? That a better sense and implementation of lower density might be a better solution?

After all, the arc right now in almost everything is de-centralization. That spreads risks out across fewer people over larger areas. What's worse - millions losing power or a few thousands (for one example)?

Have cities become too large to top-down manage well (I'm looking at Chicago, for a whole host of reasons, as a singular example)? I'm also looking at the "moral hazard" that seems to have been adopted of "it doesn't matter, the Feds will bail us out on bad decisions"?