Another major source of particulates: Tire wear

Surprise! The amount of PM2.5 and PM10 is proportional to the weight of the vehicle.

After publishing my last post, More on particulate pollution, death, DALYs and dementia, a reader asked:

“Got anything on tyres/roads? An aggregate of how much and where those are ending up? They are part of ocean microplastics pollution but how did they get there? They must also pollute rivers and groundwater? And do they get kicked up?”

It is a place I fear to tread; In 2016 I wrote about a study, Non-exhaust PM emissions from electric vehicles, in a Treehugger post titled Do Electric Cars Generate as Much Particulate Pollution as Gas and Diesel Powered Cars? and got more negative comments than any other post I ever wrote, including demands that I be fired immediately for being a shill for the oil companies. The consensus was with one commenter: “I believe this is one of the most irresponsible and MORONIC studies I've seen in years.”

While greenhouse gas emissions from cars come out of the tailpipe and are nonexistent in an electric car, the PM10 and PM2.5 emissions from vehicles come mostly from tire and brake wear. According to a UK study, “Non-Exhaust Emissions (NEE) are currently believed to constitute the majority of primary particulate matter from road transport, accounting for 60 percent of PM2.5 and 73 percent of PM10.”

The controversial electric car study noted that the amount of wear on tires and production of particulates is directly proportional to the weight of the vehicle:

“We know that road abrasion and tyre wear are caused by the friction between the tyre thread and road surface. Friction is a function of the friction coefficient between the tyres and the road, as well as a function of the normal force of the road. This force is directly proportional to the weight of the car. This means that increasing vehicle weight would increase the frictional force and therefore the rate of wear on both the tyre and road surface.”

They also determined that the average electric vehicle was 24% heavier than the ICE version of the same car. They did the math (with no contribution from brake wear on EVs) and found PM10 emissions to be marginally lower for EVs than ICE powered cars, and PM2.5 to be marginally higher.

The study was conducted in 2016, and batteries are significantly better, with EVs now only between 10% and 15% heavier than their ICE equivalent. I suspect that if the study were done today, the results would favour the EV. But that wouldn’t change the author’s conclusion:

“Future policy should consequently focus on setting standards for non-exhaust emissions and encouraging weight reduction of all vehicles to significantly reduce PM emissions from traffic.”

The real lesson from the controversy was that people simply do not understand particulates or the harm that they cause. They don’t understand resuspension, where particulates are kicked up into the air by other vehicles, often after being ground down from PM10 to PM2.5; they claimed it was “double counting.” They didn’t seem to accept that bigger, heavier vehicles pump out more particulates that are killing and maiming people. Nobody talks about this, and no government regulates it. The issue is studiously ignored.

In 2020, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) tried to raise the issue in a report, Non-exhaust Particulate Emissions from Road Transport: An Ignored Environmental Policy Challenge. It also noted that when it comes to pollution, electric cars won’t save us:

“In the context of growing travel demand, electric vehicles are widely regarded as a solution to mitigating greenhouse gas emissions and other air pollutants from road transport. While they stand to eliminate exhaust emissions, this report shows that electric vehicles are not likely to provide substantial benefits in terms of non-exhaust emissions reductions. Regenerative braking systems can reduce brake wear, but tyre wear, road wear, and road dust resuspension remain significant sources of non-exhaust emissions from electric vehicles. Non-exhaust emissions from these sources can in fact be higher for electric vehicles than for their conventional counterparts, as the heavy batteries in electric vehicles imply that they typically weigh more than similar conventional vehicles. This is particularly the case for electric vehicles with greater autonomy (driving range) that require larger battery packs.”

The OECD calls for policies to promote the "lightweighting of vehicles," promoting the use of smaller cars. Clearly, the trend to giant SUVs and pickups with bigger, heavier batteries is a problem, and the OECD calls for the inclusion of vehicle weight in calculating taxes and fees, and calls for weight limitations in cities. They also promote alternative modes to reduce particulate emissions:

“Vehicle-kilometres travelled in urban areas can be reduced using a variety of policies that disincentivise the use of private vehicles and incentivise the use of alternative modes such as public transport, cycling, and walking. As population exposure to PM from non-exhaust emissions is greatest in urban areas, urban vehicle access regulations (UVARs) such as low-emission zones and congestion pricing schemes can also be an effective means of reducing the social costs of non-exhaust emissions.”

After reading another study with a mouthful of a title, Tyre and road wear particles (TRWP) - A review of generation, properties, emissions, human health risk, ecotoxicity, and fate in the environment, I was even more upset at our willful blindness to address particulates. It shows that it runs off into watercourses where it is toxic to marine life, and that it is in the air we breathe, “TRWP were detected in aquatic compartments, in ambient air, road dust and soils.” The authors also note that there is not nearly enough research being done, but they do have recommendations:

Improvement of runoff treatment systems at rural roads and highways according to the state of the art, regular control and maintenance of drainage systems including disposal of sediment

Incineration of sewage sludge containing large proportions of road runoff sediments instead of spreading on agricultural areas or natural soil,

Regular maintenance of roads and successive optimization of roads surfaces,

Promotion of lightweight vehicles,

Incentives for avoiding transport, use of the combined intermodal traffic, creating awareness, e.g. regarding driving behaviour,

Implementation of speed limits,

Optimisation of tyre materials with regard to higher durability and wear resistance taking into account safety and other essential requirements.

My dear reader wondered if particulates from tires ended up in the ocean; a report by the Pew Charitable Foundation claimed that “seventy-eight percent of ocean microplastics are synthetic tire rubber.” From an article in Yale Environment 360:

“We found extremely high levels of microplastics in our stormwater,” said Rebecca Sutton, an environmental scientist with the San Francisco Estuary Institute who studied runoff. “Our estimated annual discharge of microplastics into San Francisco Bay from stormwater was 7 trillion particles, and half of that was suspected tire particles.”

Another study found Tons of tire rubber is making its way to the Arctic each year.

“Suspicion that microplastics — including those stemming from tires and brakes — was being transported to remote areas by the atmosphere and deposited by snow was confirmed last year by the Germany-based Alfred Wegener Institute. In one sample collected from Svalbard, AWI recorded some 14,400 particles of microplastics — most measuring less than 100 micrometers, or about the thickness of a sheet of paper — per liter of snow.”

After reading the Arctic study, I concluded that we need fewer, smaller, lighter and slower cars.

“Bigger, heavier cars cause all kinds of problems. They consume more fuel, they cause more wear and tear on infrastructure, they take more room to park, they kill more pedestrians both by hitting them and by poisoning the air with exhaust from ICE powered cars, plus particulates from every kind of car, no matter what is pushing it.”

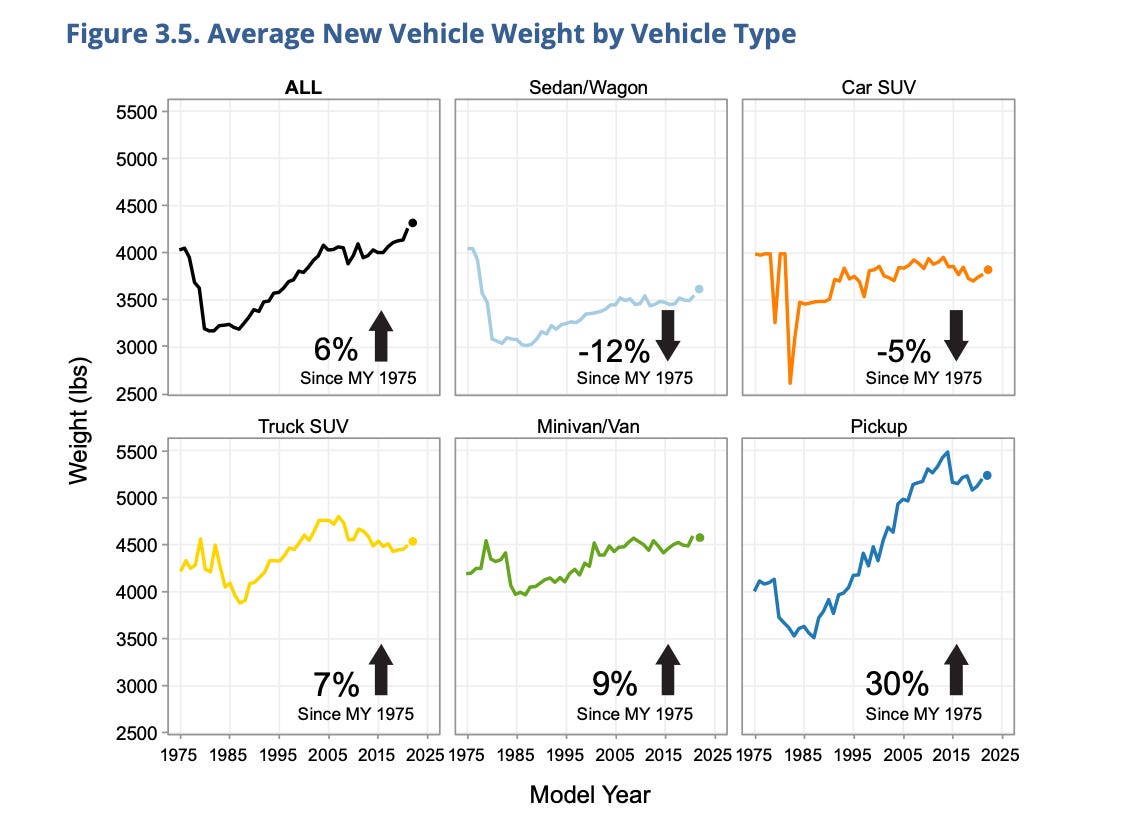

I am not alone; every study and report noted that we should be making lighter vehicles and promoting alternatives to driving. Meanwhile, according to the EPA, cars and trucks just get heavier, with pickups growing an amazing 30%.

Cities also have to stop approving high-density housing so close to highways; In Toronto, apartment balconies hang over the Gardiner Expressway; I wonder if anyone is measuring what they are breathing. One report notes:

“Ultrafine particles are the smallest and possibly the most dangerous of these particles. Because they are so small, they can get inside the body more easily, where they can cause disease. Researchers suspect the health risk from ultrafine particles is greatest downwind and within 300ft or 100m of a busy highway.”

And here we are in Toronto with residences essentially zero meters from the highway.

Nobody wants to talk about particulate pollution. After all, they have been killing and injuring us since we discovered fire; what’s new here? The auto industry certainly doesn’t want to acknowledge it, nor do politicians like Ontario’s Doug Ford who are ripping up bike lanes and increasing speed limits. However, particulates are in our air, in our water, in our lungs and in our brains. We have to talk about it.

Special offer!

I do not want to put up a paywall on this site, but it provides a meaningful portion of my income. So here’s a limited-time offer: I will send a signed copy of the print edition of “Living the 1.5 Lifestyle” to anyone in the USA or Canada who signs up for a one-year subscription (C$50, cheap at about US$35- US$37-the dollar is falling ). I am running out of stock, so hurry!

Fully agree with your article. I think you should add something about moving heavy cargo by truck as well. Not all the particulates from these big rigs come from the diesel engine, though the black clouds at stop lights are annoying when I ride my bike. The Greenland ice sheet albedo problem is mostly caused by particulates from tires, though forest fires may have passed them now. Feedback loops. The problem is the car overall. I have 10,000 miles on my bike tires and they show almost no sign of wear. If we can get the cars and trucks off the roads, at least in part, a lot more people would ride, instead of just crazy people like me.

Yup. There is also a deforestation problem with tires. Most latex rubber from trees goes to make tires.