An alternative vision of transportation, from my Dad

He believed that freight and people shouldn't mix on the roads. He was right.

Sitting on the train going to Ottawa for the National Trust for Canada conference last week, looking to the right, I saw hundreds of huge transport tractor-trailer rigs with names like TFI or CN on Highway 401; I counted 30 passing in the opposite direction in 30 seconds, often with cars zipping in and out around them. To the left, I often saw intermodal shipping containers with names like Maersk or Cosco or ZIM, the standard boxes used for international shipping on ships, trucks or rail. And I thought about my dad.

Gabe Alter, seen here in the early seventies with chief engineer Mike Hand, was president of Steadman Containers and a pioneer in the container industry. Dead now for 26 years, he would have been outraged had he been sitting on the slow, shaking train while seeing all those transport trucks on the 401.

Back in the late sixties, the era of the Interstate Highway System and the 747, he would tell me that "freight belongs on rails, and people belong in planes and cars; it is crazy to mix them up on the roads." He projected terrible congestion on the highways and in the ports if transport trailers kept taking more of the freight that the railways used to carry in their old boxcars. He was certain that many would die in crashes between cars and trucks, that it was a fundamentally dangerous combination.

At the time, almost every crash involving trucks and cars ended in death. Even today, the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety notes:

“Trucks often weigh 20-30 times as much as passenger cars and are taller with greater ground clearance, which can result in smaller vehicles underriding trucks in crashes. Truck braking capability can be a factor in truck crashes. Loaded tractor-trailers require 20-40 percent more distance than cars to stop, and the discrepancy is greater on wet and slippery roads or with poorly maintained brakes. Truck driver fatigue is also a known crash risk. Drivers of large trucks are allowed by federal hours-of-service regulations to drive up to 11 hours at a stretch. Surveys indicate that many drivers violate the regulations and work longer than permitted.”

Gabe would also complain about the economic cost; every one of those trucks has an overworked and underpaid driver sitting in a $200,000 tractor. If he were in the next seat, I would complain about the particulates and carbon emissions; at an average of 161.8 grams per ton-mile, a truck carrying 20 tons for a thousand miles emits 3.24 tonnes of CO2.

Most of these trailers are carrying domestic freight, often from giant warehouses to stores. They are big and getting bigger as companies try and get more out of each driver. They are often too big for cities, getting stuck on corners and killing not a few cyclists and pedestrians. They shouldn’t be there, and if Gabe had his way, they wouldn’t have been.

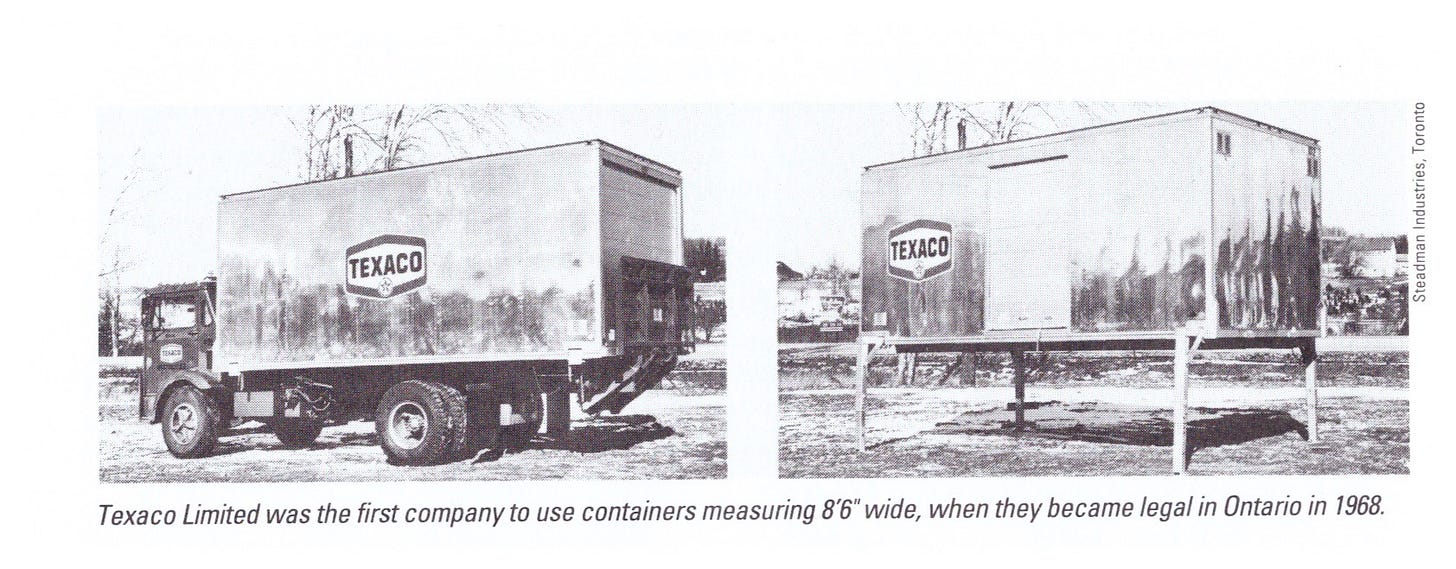

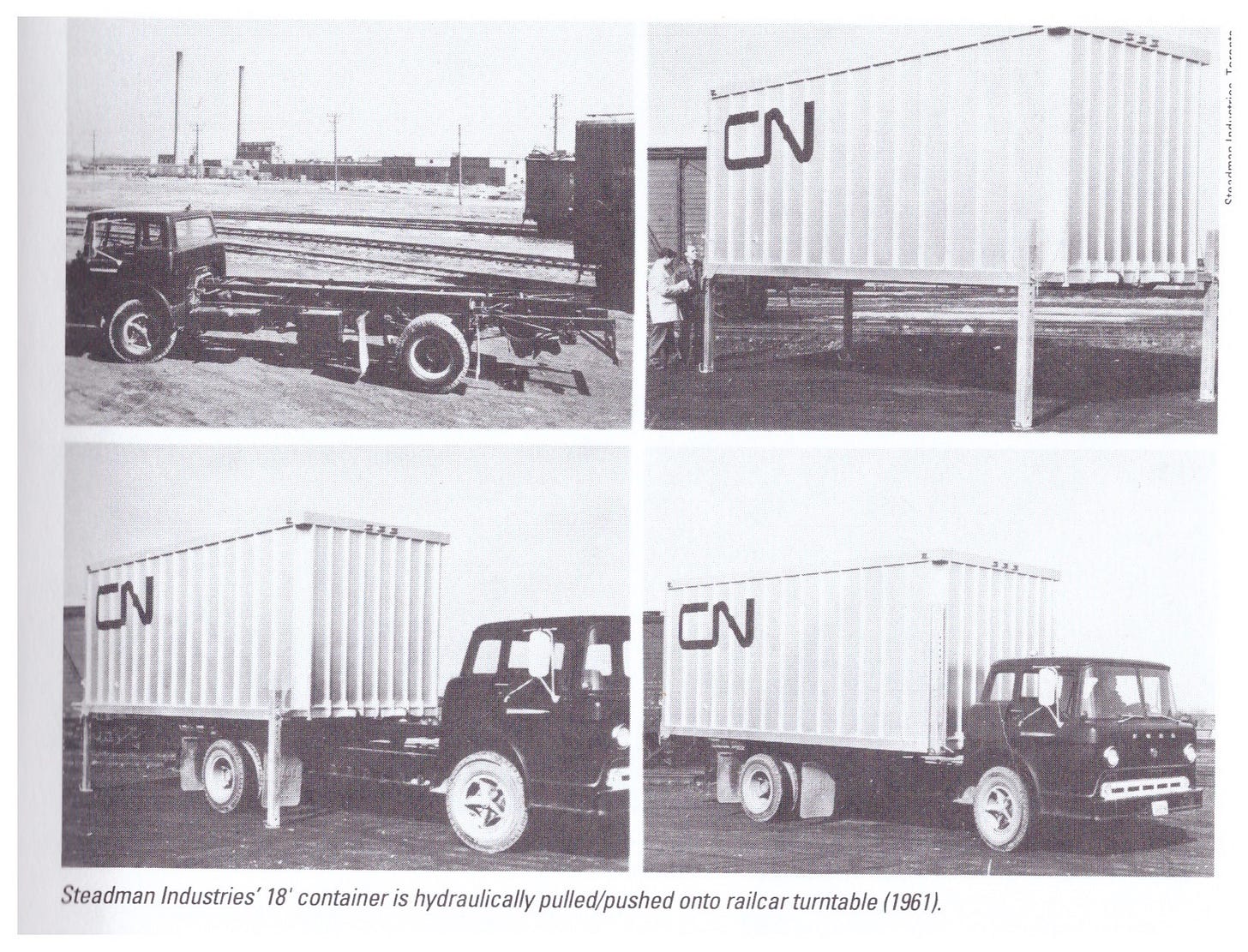

Back in the 60s, when there were no agreed international standards for containers, there was an explosion of technologies and experimentation. Steadman Containers first developed container technology for domestic use. The truck might pull up to a loading dock, hydraulically lift to dock level, and then the driver would install four aluminum legs in sockets at the corners. The truck would then drop back down and drive away. Why waste those wheels and chassis just sitting there?

But the killer app was the side-transfer Railtainer unit. There were no cranes and no container infrastructure, so systems had to be developed to do the job independently. These special trailers had hydraulics that would slide the container from a trailer over onto a train. Mike Hand, a transportation historian as well as an engineer, describes the first time they tried it in 1963:

“Driving alongside the railcar, with a trailer carrying a 20-foot container with 25,000 pounds of weight, we used hydraulic legs to raise the trailer until the slide angles on the trailer and the railcar were level with each other and held our breath. The operator extended the cylinder, pushing the container sideways while we eyed the side of the container to see how much it would bend. Nothing. No deflection at all! The container slid sideways onto the railcar bolsters as smooth as one could wish. Rotating the hook on the end of the cylinder so that the pull portion was upwards, the container was then pulled back onto the trailer, the cylinder ratcheting backwards and forwards smoothly as the container skidded sideways. Gabe and I were elated and could hardly believe that our first attempt worked so well.”

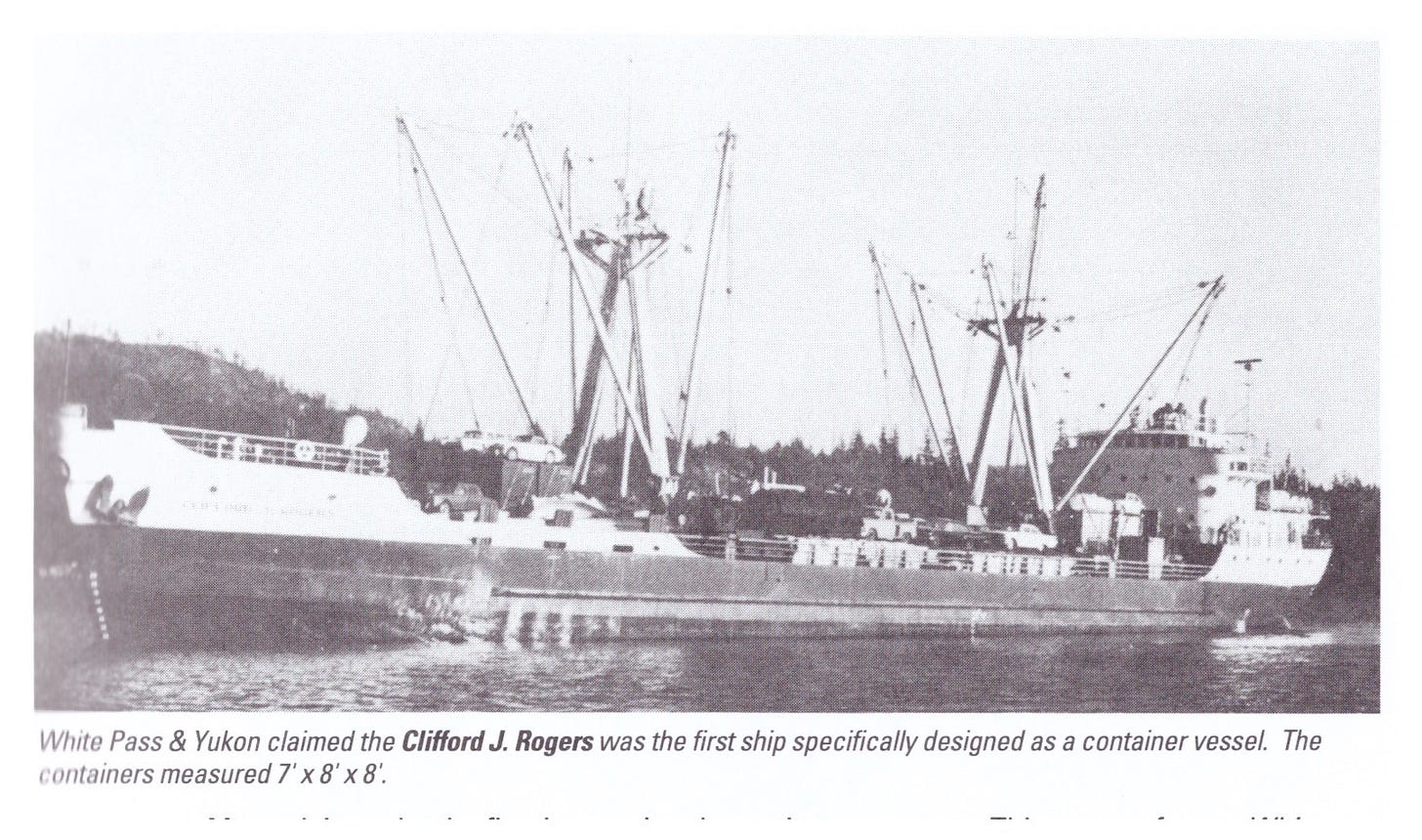

It’s generally accepted that Thomas Edison invented the lightbulb (he didn’t) and Malcom McLean invented the intermodal shipping container and that he built the first container ship; even Wikipedia says so, as does Marc Levenson’s book “The Box.” He didn’t. The reality is different- According to Peter Hunter in “The Magic Box-A History of Containerization,” the White Pass and Yukon Line was carrying containers on a fully intermodal run by ship, rail and truck between Vancouver, Skagway, and Whitehorse in 1953 and built the first container ship, the Clifford J. Rogers, in 1955. Canadians were pioneers in this industry, but Americans wrote the history.

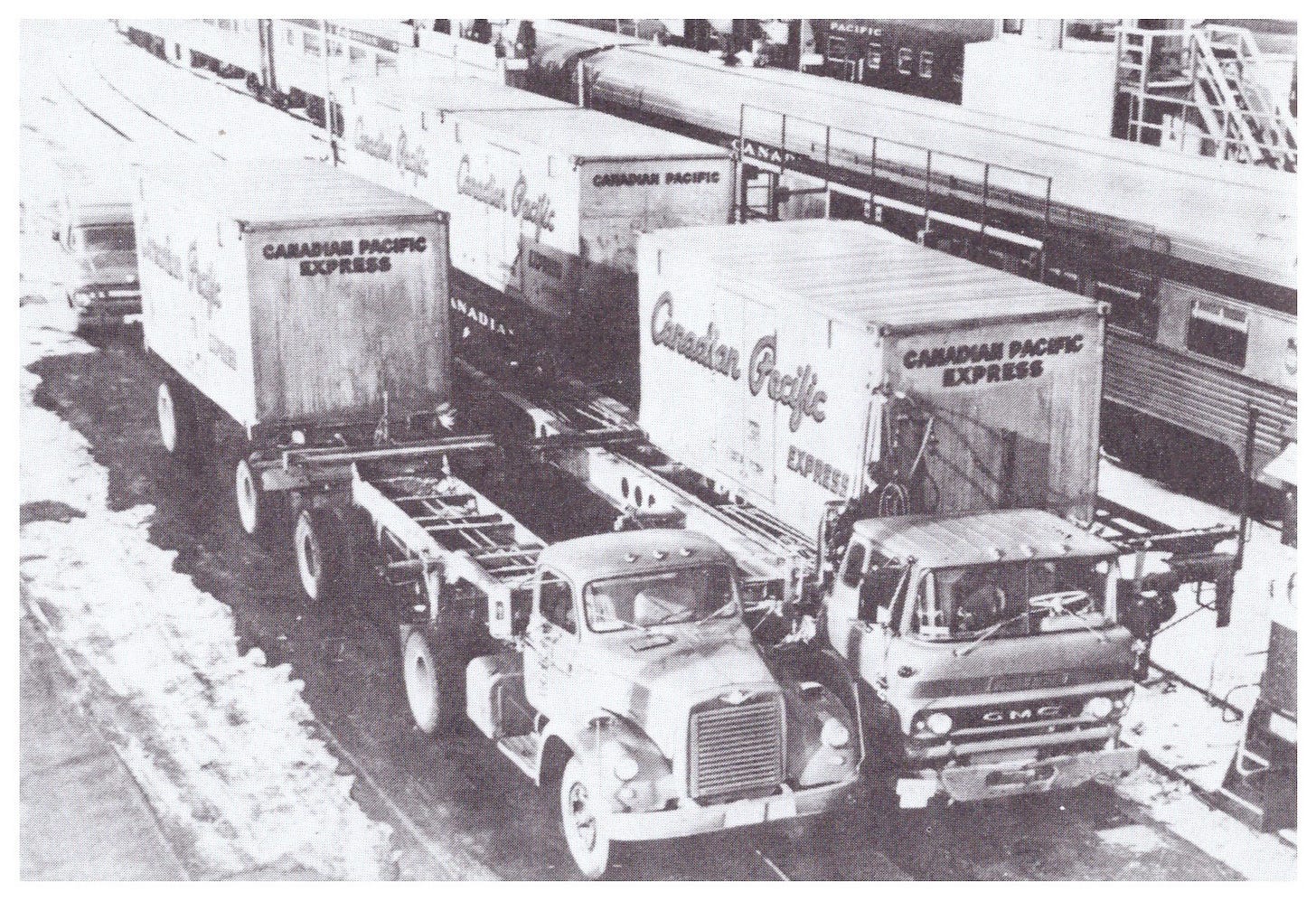

Nor was there a standard intermodal container at the time; a Canadian, Don Francis of Canadian Pacific noted at a conference in 1962: “To fully exploit the benefits of containerization, there must be standardization of container sizes within the shipping industry. This is a prerequisite of an integrated container system.” That didn’t come until 1967 at the Genoa International Container Conference, attended by my dad and Don Francis. My dad caused a stir at the conference with his proposal for a “land bridge” of shipping containers travelling by rail across Canada.

The land bridge and the side-transfer container system were supposed to handle domestic freight across the country. Goods would pass from ship to rail in Halifax or Vancouver and then slide off the rail onto a truck in Toronto or anywhere near the land bridge for local delivery. Long distances were done by rail with hundreds of boxes on a train, and short distances were served by small trucks carrying the same container. Peter Hunter called it “a low-cost, efficient method of movement by road and rail, transferring between modes and positioning at receiver’s or shipper’s doors.”

People would travel using a safe and separate fast passenger rail and supporting road network, and those 747s.

It was not to be; Gabe and Don Francis of CP tried to get the side-transfer slide angles accepted as a standard, and it was rejected. The approved International standard (ISO) container had corner castings that were lower than the box, so it wouldn’t slide properly on the angles, essentially making the entire Railtainer side-transfer concept obsolete. Steadman developed equipment that could handle the new standard containers (I took the photo above in Columbus, Ohio, a little job Dad gave me when I was in university), but it was too slow and expensive.

The biggest blow came in 1968 when Malcom McLean and Sealand got a contract to deliver 1200 containers per month to South Vietnam. The war traffic was so huge that giant container ports with overhead cranes were built, fed with containers on trucks going from factory to port, running on the Dwight D. Eisenhower Interstate and Defense Highway Network paid for by taxpayers. The rail systems paid for their own infrastructure but lost their passengers to planes and a lot of freight to trucks and couldn’t compete or invest in new equipment or proper maintenance.

Both Canadian National (CN) and Canadian Pacific (CPRail) made big investments in their systems, but there was no way that Canada wouldn’t have to follow the American model that ran on trucks and roads.

My dad was right. These transport tractor-trailers did not belong on roads with mixed traffic. Thousands of people are killed each year, billions of tonnes of CO2 are emitted, and vast quantities of concrete are poured to build and maintain their infrastructure.

But it was hard to compete with the subsidized Interstate Highway and Defense System and a war in Vietnam. Steadman Containers didn’t last long after that; My dad moved on and, in one of those “if you can’t beat’em, join’em” things, ended up running a transport trailer leasing business.

As I sat on the rattling slow train home from Ottawa, half an hour late because it runs on CP rails and has to stop often to give freight priority, I thought about my late father’s alternative vision of a system where freight and passengers have safe and separate systems instead of me being stopped on a freight rail line while giant trucks clog the highways. It would likely have worked, and North American transportation (and my ride home) might have been very different.

Great story, and great points made.

In your copious spare time, you should correct the Wikipedia entry. Anyone can correct Wikipedia, I've done it myself. [Wikipedia does have content monitors, to catch people posting jibberish, but documented corrections will stand.]

Ugh.... 😢