An all-electric multi-modal vision of the future

Electric cars are glorious, but they cannot be allowed to dominate e-transportation.

I was recently in The Netherlands as a guest of the bike manufacturer Gazelle to “experience the Dutch cycling culture, infrastructure, and bikes firsthand.” I have often written that we need three things for an e-bike revolution: good bikes, safe places to ride, and secure places to park. In the Netherlands, they have all three in spades.

But there was another lesson from this trip; it demonstrated the future of an all-electric world where people who drive, people who bike and people who walk can perhaps co-exist, but only if we are diligent in ensuring that cars don’t continue to dominate.

It started from the moment I stepped out of the airport and got into a Volkswagen ID Buzz, an electric VW bus with a 350 km range. Its footprint is no bigger than our Subaru Impreza, and it seats 5 (the promised American version is a foot longer and will have a third row; there are evidently tax reasons for not doing this in Europe). It was smooth, comfortable and quiet.

Chris Bruntlett, formerly of Vancouver and now in Delft and working for the Dutch Cycling Embassy, extols the virtues of Dutch cycling, but the fact remains that the car is the most popular means of transport in the Netherlands. David Hembrow notes in an article titled “The car-free myth” that driving is subsidized with a tax benefit, the roads are still being expanded, and there are more cars on the road than ever before.

“The Netherlands has built the most comprehensive grid of mostly very high-quality cycling infrastructure anywhere in the world, but we are still failing to make cycling attractive enough to encourage people not to use motorized transport because actually, we are still encouraging people to make ever more and longer journeys.”

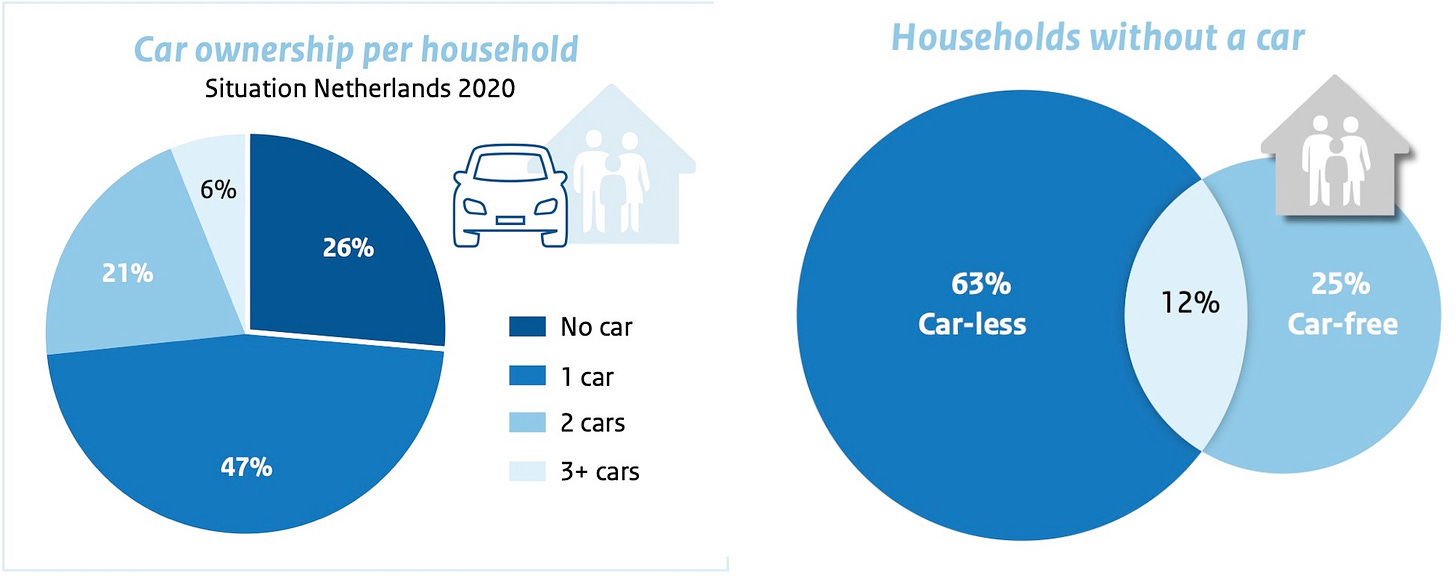

This is confirmed in a 2022 study by the KiM Netherlands Institute for Transport Policy titled “The widespread car ownership in The Netherlands,” which notes that The Netherlands has more cars per capita than France, Sweden or the UK, and “when calculated per square kilometre of land area, no neighbouring countries can match the Netherlands: within the EU.” Also: “Since 1990, car ownership in the Netherlands has increased from 0.8 to almost 1.1 cars per household.” All of those horrible North American urban trends are happening in The Netherlands.

“Increased car mobility is driving the growth of the car system, including more roads, tunnels, parking lots, garages and gas stations, thereby giving all motorists, and not just newcomers, more possibilities to use the system. Sprawl and economies of scale result from the high speeds associated with motorized transport: megastores are replacing neighbourhood supermarkets, work locations become office parks, residential areas become more spacious, activities are spread out spatially, and the distances everyone must travel increase.”

The study sees growing car dependency but notes that “The vicious circle of car dependency only applies to a certain extent to the Netherlands, thanks to the country’s effective spatial policies and support for public transit and bicycles. In large Dutch cities, we even observed a reverse movement towards fewer cars. Conversely, rural areas are vulnerable to increasing car dependence.”

The study also notes that “certain local developments, like in Amsterdam or Utrecht centre, emphatically do not benefit motorists; examples include the narrowing or removal of roads, reductions in numbers of parking places or the lowering of speed limits.” We visited those cities, along with Gazelle’s hometown of Dieren, so we got what was perhaps a more rose-coloured view of the overall picture.

It is clear that what the Dutch do, that we don’t in North America, is that they accommodate all modes of transport instead of prioritizing the automobile. And where appropriate, like in the cities, they seriously prioritize walking, biking, and public transport. But it is still not enough.

Having spent four days moving from e-vans to e-cars to e-bikes and even e-canal boats, one can see a different vision of the future, with a place for every e-vehicle and every e-vehicle in its place. Two days of riding the new Gazelle further convinced me that the e-bike, not the e-car, should be the transformational vehicle of the next decade.

Amsterdam needs a transformational vehicle. Walking home one evening from a dinner out (which, almost every time, was faster than taking the VW bus), I took this postcard shot of a canal. But if you look closely, it is lined with cars at the water’s edge.

You have to walk in the road because cars are everywhere. Even the trees need protection from BMWs. The edge of the Amstel should be a promenade, not a parking lot.

The KiM study found that only 26% of households in The Netherlands did not own a car, and of those, 63% were car-less, “these are people who do not own cars due to health reasons, old age or financial problems. These people do not necessarily want to be car-less.” Only a quarter was “car-free” -6% of all households –who deliberately do not own cars; they see no associated added value or are concerned about the climate or environment. This is a national number and will likely be much higher in the cities, but it is still surprisingly low. (The 12% overlap is “an intermediate category, which cannot simply be described as car-free or car-less.”)

I thought the ID Buzz was a glorious vehicle, a worthy descendant of the original Type 2 VW bus.* Similarly, I loved being driven in the ID3 electric car. If I were ever to buy another car, this would be it. But just changing every car in Amsterdam to electric doesn’t give us a promenade along the Amstel.

Here’s a country that builds glorious bike infrastructure; Chris Bruntlett described how you could cycle between cities on bicycle highways and never take your feet off the pedals. The streets are designed to make it safe and comfortable to ride.

We zipped around Amsterdam and Utrecht on our Gazelle e-bikes, and there were only occasional moments of discomfort, primarily when negotiating with other bikes. I was even secretly pleased that they made us wear helmets; streetcar tracks are everywhere and are often the cause of falls where helmets are useful.

In 22 cities across The Netherlands, there are enclosed secure parking garages at train stations, and in Utrecht and Amsterdam, there are vast underground facilities. Yet the number of people driving is still increasing. I heard anecdotes about how even driving kids to school in cars, not cargo bikes, is becoming more common.

Four days in The Netherlands riding all kinds of electric vehicles convinced me they are all wonderful and have a role to play. My first photo was taken from outside of an ID Buzz van; my last photo was taken from inside one. But they are still cars; they still clog the streets or, in Amsterdam, the canals. They still need all this expensive car infrastructure. I may have spent four days without burning a teaspoon of fossil fuels while on the ground, but I still got stuck in traffic.

David Hembrow noted even the Dutch “are still failing to make cycling attractive enough to encourage people not to use motorized transport.” If they can’t do it, nobody can. But perhaps the e-bike can make a difference; I believe it can be the transformational device that will let more people travel farther with less effort and can be a plausible alternative to cars in many cases. It is that the third leg which, along with safe places to ride and secure places to park, may change this picture. And I will describe in my next post how e-bikes are better than ever.

*In an interesting twist of history, the idea of the original van was drawn up during a 1947 visit to Wolfsburg by Ben Pon, the Dutch importer of VW Beetles after the Second World War. In 2011 Pon Holdings bought Gazelle.

Great post Lloyd. Seems like the Netherlands should stop subsidizing electric cars.