Air conditioning is a hot topic these days

The CBC interviewed me about the subject; my views on it are changing because the climate is changing.

How bad is air conditioning for the climate, and how can we live without it or minimize its use? These were some of the questions I was asked on Here and Now, the afternoon drive-home show on Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) in Toronto, earlier this week. It was not easy to answer; so much has changed, and my pat responses from a few years ago no longer work.

CBC: How do we keep cool if we don’t have air conditioning?

I always used to fall back on a wonderful article by Barbara Flanagan from 2007, A cold day in Hell, describing how people live in Barcelona.

Rather than rely on machines and wreck their old architecture with window units and ducts, they design their habits, hardware, clothes, and attitude to cool themselves off. Now their deference seems sustainably avant-garde.

The secret to Catalan comfort is not a gadget, but a self-induced, mind-body state of discomfort suspension: heat tolerance. When it’s summer, everyone expects to be hot. Accordingly, they plan their seasonal vacations, daily routines, food, drinks, and wardrobes for maximum cooling. In other words, it’s the culture that cools, not the contraptions.

My recommendation for the Toronto version of this was to pretend that you are in Barcelona and go to parks or the waterfront, dress in loose clothing and eat late outside, enjoying everything the city has to offer in summer. Get outside! Be part of society! I wrote earlier that “we are sacrificing neighbourhood and community by forcing our immediate personal climate to adapt to us instead of us adapting to it.”

But that’s all fine when the temperature is 30°C as Flanagan might have found it in 2007. It’s another story when temperatures in Spain are hitting 45°C as they are in this heat wave.

As I write this, the Toronto area is under a heat alert, with the Humidex at 40°C. Sitting by the puppy fountain isn’t going to do it.

Flanagan also described how many use their dwellings to keep cool.

Dwellings adapt. Double-door-size windows have three layers: usually metal shutters, glass sashes, and drapes. (No bugs, no screens. In the early morning, residents throw open windows; in mid-afternoon, they close the shutters to block the heat.)

These Catalan design tricks and night-flush techniques used to work in North America too; A 2021 study, "Improving the passive survivability of residential buildings during extreme heat events in the Pacific Northwest" found that they could reduce heating loads by up to four-fifths. It and other studies show why good design is the best answer to avoiding the problem of A/C:

"Air conditioning alone is neither a desirable nor an effective solution: operation requires electricity, which is regularly compromised during heat waves by sagging power lines and extreme demand peaks; additionally, operational efficiency is diminished and unit capacities are often exceeded during heat waves; equipment purchase and maintenance needs create vulnerability to limited funding; and the hot air expelled exacerbates urban heat island effects, which are already intense in Vancouver, Seattle, and Portland."

But even in Vancouver this year, the heat waves have been intolerable, and the government has been handing out air conditioners.

In many ways, people no longer have a choice because their homes are so badly designed. They used to have passive survivability because active air conditioning didn’t exist. Houses had high ceilings, tunable double-hung windows, cross-ventilation and porches. Houses were designed differently if they were in different parts of the country. Fossil fuels and air conditioning changed all that; as Reyner Banham wrote in The Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment about HVAC, back in 1968:

“By providing almost total control of the atmospheric variables of temperature, humidity and purity, it has demolished almost all of the environmental constraints on design that have survived that other great breakthrough, electric lighting. For anyone who is prepared to foot the consequent bill for power consumed, it is now possible to live in almost any type or form of house one likes to name in any region of the world that takes the fancy. Given this convenient climactic package one may live under low ceilings in the humid tropics, behind thin walls in the arctic and under uninsulated roofs in the desert.”

Professor Cameron Tonkinwise said much the same thing:

"The window air conditioner allows architects to be lazy. We don't have to think about making a building work, because you can just buy a box."

Today, we should be designing our homes to use less of it. Engineer Ted Kesik wrote the Thermal Resilience Design Guide, with his call for “thermal autonomy, where you design your building to need as little heating and cooling as possible, for as much of the year as possible. Doing this reduces energy consumption, extends the life of mechanical equipment, and reduces peak demand on the energy grid, an important consideration if we are going to electrify everything."

"Since the beginning of human history, passive habitability has driven the design of buildings. It is only since the Industrial Revolution that widespread access to plentiful and affordable energy caused architecture to put passive habitability on the back burner. Climate change is influencing building designers to rethink building reliance on active systems that became dominant during the 20th century."

Other suggestions of mine for living without AC included turning everything off, drinking lots of fluids, and using a fan, but be sure to turn the fan off when you leave the room; it is cooling you by evaporation, not the room. Allison Bailes had good advice about fans. I also really like this advice from the Extinction Rebellion gang in the UK:

Alas, XR is correct here; ice cream is nice, but we know what we really have to do.

CBC: How bad is air conditioning for the environment?

Here, the answer depends on where you live. In much of the world, the air conditioner runs on electricity made with fossil fuels, so it is a real problem. As William Saleton wrote years ago in The Deluded World of Air Conditioning:

"Air conditioning takes indoor heat and pushes it outdoors. To do this, it uses energy, which increases production of greenhouse gases, which warm the atmosphere. From a cooling standpoint, the first transaction is a wash, and the second is a loss. We're cooking our planet to refrigerate the diminishing part that's still habitable."

In Canada, at least in Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia, most of the electricity is low carbon from hydro or nuclear. In Ontario, there are gas-fired peaker plants that spin up to meet peak demand, which comes in summer from air conditioning on hot, humid days. So people should look at their electrical bills and find out when cheaper, off-peak power is available. In Toronto, peak power from 11 AM to 5 PM, so you will save money and emit less carbon if you cool down before or after those times.

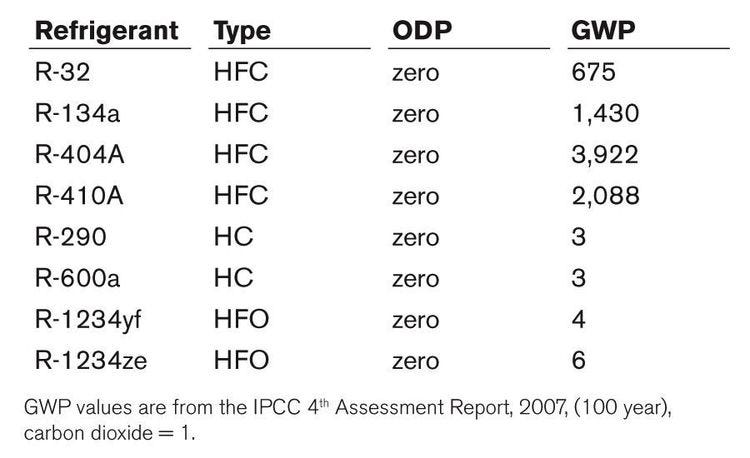

The refrigerant in your air conditioner matters; they leak, and many refrigerants are serious greenhouse gases. Most today are filled with R-134a,* which is still 1,430 times as bad as CO2. Units with R-290, plain old propane, are almost standard in Europe but as Phil McKenna of Inside Climate News notes, the producers of more expensive and proprietary refrigerants have fought the introduction of R-290, noting:

"HFCs are multi-billion dollar products that would likely be replaced by less expensive and more efficient climate-friendly alternatives if standards put forth by Underwriters Laboratories didn’t until recently limit their use, likely at the behest of chemical companies."

So if you are buying an air conditioner or heat pump, demand R-290.* It’s still hard to find, but it is becoming more available.

*UPDATE

Victor Hyman of ClimateCare Canada notes that I have a few things wrong here.

“All residential air conditioners on the market today in North America use R-410A, not R-134A. That will make your point a little more compelling because the GWP of R-410A is higher than R-134A.”

He also notes that my dreams of R290 are wishful thinking.

“R290 is not in use for air conditioners or heat pumps yet in North America, so telling people to ask for them is just going to cause confusion and upset. R32 is being used by some manufacturers already for portables and window units. There is a mad rush by industry to get equipment and codes aligned for 2025 and the lower GWP requirements that will move us to A2Ls like R32 and R454. I don’t expect R290 to make it into split system ACs and HPs for at least a decade.”

CBC: What can we do to make our cities cooler?

Plant trees! As a former London city councillor noted last year, they are natural air conditioners. Professor Roland Ennos wrote in the Conversation about how trees keep us cool:

"Theoretically, trees can help provide cooling in two ways: by providing shade, and through a process known as evapotranspiration. Locally, trees provide most of their cooling effect by shading. All up, the shade provided by trees can reduce our physiologically equivalent temperature (that is, how warm we feel our surroundings to be) by between seven and 15°C, depending on our latitude."

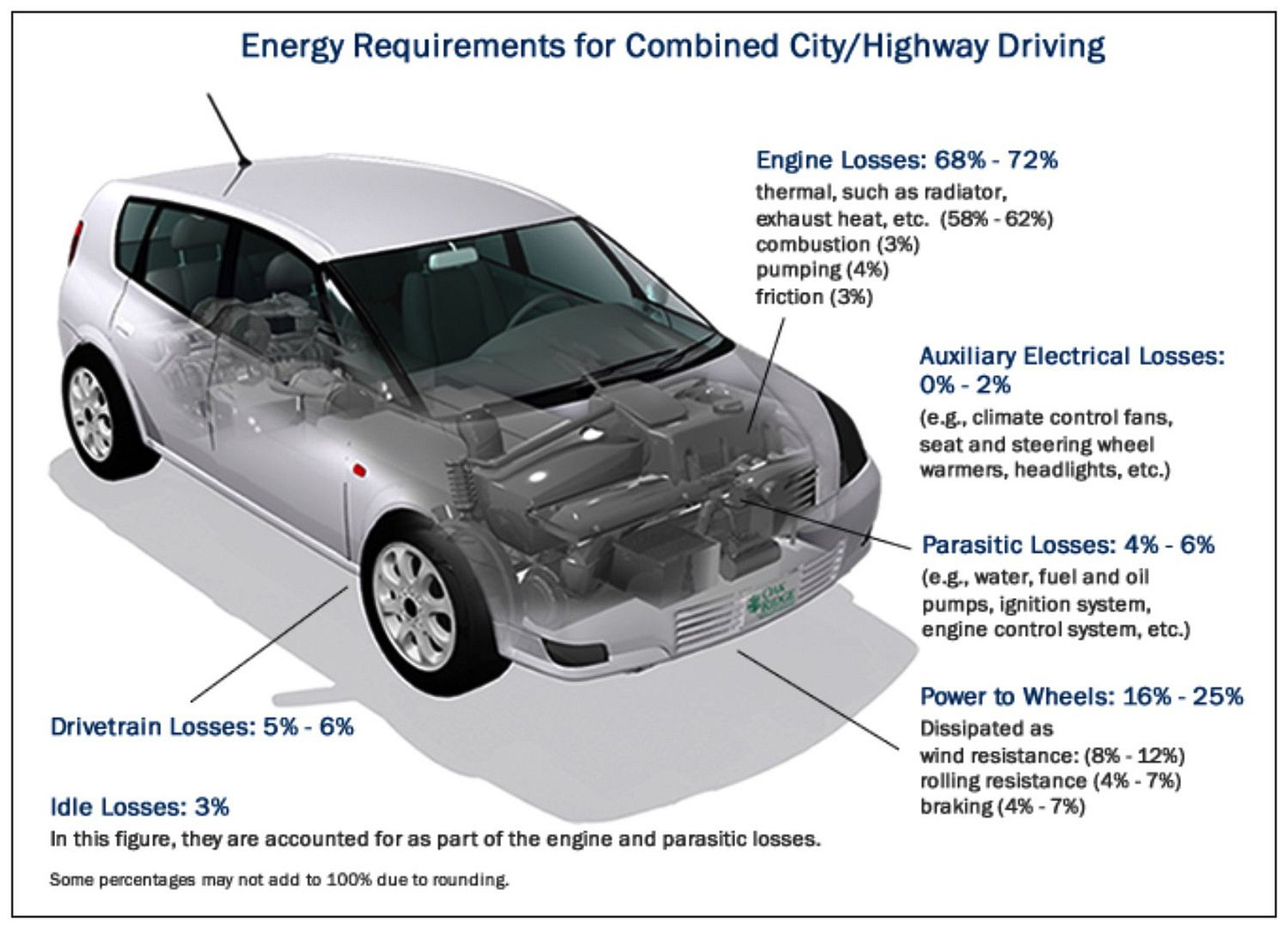

Get rid of cars! It’s bad enough that their CO2 emissions contribute to heating the planet, but they do it directly in our cities too. The US Office of energy efficiency says 68% to 72% of the gas is lost as heat, but others say it is much higher. Mechanical engineer Steve Blumenkranz noted, "The heat dissipated by a car by all loss mechanisms combined is equal to the heating value of the gasoline burned by its engine. All of the energy in the fuel is eventually dissipated as heat."

In a Treehugger post a few years ago, I tried to figure out how much heat was emitted and convert it to a scale people understood; I calculated that driving an average car around the city was the equivalent of four patio heaters running full blast. I then did the math for cars in Manhattan and concluded it was the equivalent of 157,336 patio heaters running around the city in a heat wave, noting that “perhaps when the heat is on, we should be turning the cars off.” And while converting to electric cars helps, that’s just the beginning;

“Given the amount of asphalt they need for moving and parking—all of which contribute to the heat island effect, and much of which could be used to plant trees—perhaps we should just get rid of most of the cars if we are serious about cooling our cities and reducing both heat and carbon emissions.”

Air conditioning is no longer a luxury, it has become a necessity.

The industry has been saying that since 1955, and in most cases, it’s now true. The world is getting hotter, and not everyone is as lucky and spoiled as I am, to have been able to buy a nice old cross-ventilated house on a tree-lined street. But even that doesn’t work anymore; after splitting our house into two units, I had to put AC in the upstairs apartment to make the 3rd floor habitable.

Even Alex Wilson of BuildingGreen and the Resilient Design Institute, writing from Vermont, admits:

I’m increasingly feeling that passive cooling won’t be enough as climate change advances and cooling loads increase. I’m now recommending that in most locations, even if passive conditioning is to be relied on initially, buildings be designed so that they can accommodate mechanical cooling measures down the road.

Older people, people in glass apartments, and people living in much of the world that is breaking every temperature record all need air conditioning now. So we have to build better buildings with passive cooling and thermal autonomy, but also more efficient air conditioners with low carbon refrigerants. But most importantly, we have to stop burning fossil fuels to keep the world from getting even hotter.

No mention of humidity? Or how heat stresses the human body among the chronically ill and elderly who require a more temperate living condition using modern HVAC? Or of what to do with all the tens of millions of suburban homes who are NOT built according to turn of 20th century standards with high ceilings, cross-breeze transom windows, and the like?

Look, you're not going to ever convince anybody to plow under vast swaths of suburbia and rebuild to much more dense housing levels; you're not going to convince most people to lower their comfort level willingly, for any reason; you're not going to have a viable mass transit system running on frequent timelines through suburbia into (presumably) city centers, so I see all of this as a matter of tilting at windows like Don Quixote.

Can more trees be planted? Sure—but they need to be nurtured, and it takes decades for them to reach maturity, something that is not a "quick fix". Likewise, getting rid of cars isn't realistic to a large extent either because of the preexistence of suburbia. About the only thing that works is to acclimate one's self to a wider range of temperatures and humidity levels.

I'm surprised that the A/C "issue" is even an issue because peak solar power generation is from noon to 4 pm, and there are many instances of electric utilities having negative spot prices [read: they pay YOU to use more energy than necessary because too much is being made]—the same time of day that peak A/C use is required.

I like the article as much as an HVAC guy can 😁

Need to correct a couple of points:

1) All residential air conditioners on the market today in North America use R-410A, not R-134A. That will make your point a little more compelling because the GWP of R-410A is higher than R-134A.

2) R290 is not in use for air conditioners or heat pumps yet in North America, so telling people to ask for them is just going to cause confusion and upset. R32 is being used by some manufacturers already for portables and window units. There is a mad rush by industry to get equipment and codes aligned for 2025 and the lower GWP requirements that will move us to A2Ls like R32 and R454. I don’t expect R290 to make it into split system ACs and HPs for at least a decade.